The day William Tyrrell vanished

At the time William Tyrrell vanished he was playing a game of hide-and-seek with his sister. It’s a day that will be closely examined again.

Mid-morning on September 12, 2014, Paul Savage was inside his house on Benaroon Drive, Kendall, in the green and tranquil river valley of Camden Haven on NSW’s mid-north coast.

Then aged 70, Mr Savage had seen the little boy named William and his sister, who came to stay with their grandmother directly across the road, only occasionally.

“Very few people around here knew him and his sister, not many of us, just two little kids visiting,” Mr Savage told news.com.au.

“They wouldn’t go wandering. They would stay close to their grandmother.

“You’d never see them unless you were walking or driving past.”

It was a Friday and across at number 48, William Tyrrell and his sister were playing a version of hide-and-seek in which the hider, when found, would jump out and roar like a lion.

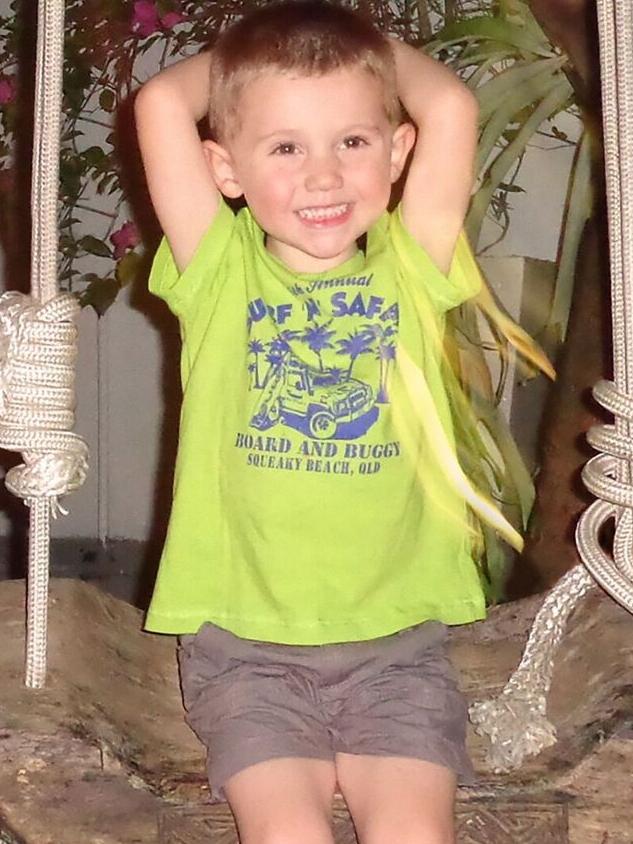

Three-year-old William and his older sister had arrived early at the house the night before as a surprise for his foster grandmother.

Just before 9am, his foster grandmother had opened the sliding doors on her veranda to look at a kookaburra and noticed two cars parked in the street.

Minutes later, William and his sister were riding their bicycles in the property’s driveway, when a car drove past, did a U-turn in a neighbour’s driveway and drove off.

Around this time, Judy Wilson, whose property was just metres from William’s grandmother’s yard, heard the two children playing before she took off to run errands in town.

The house on the block adjoining the other side of the grandmother’s yard was also empty, with the neighbour away.

Around 9.15am, William’s foster father left the house to find better reception away from the estate’s notoriously bad phone signal.

He headed for town to make a business-related Skype call, and go to the chemist.

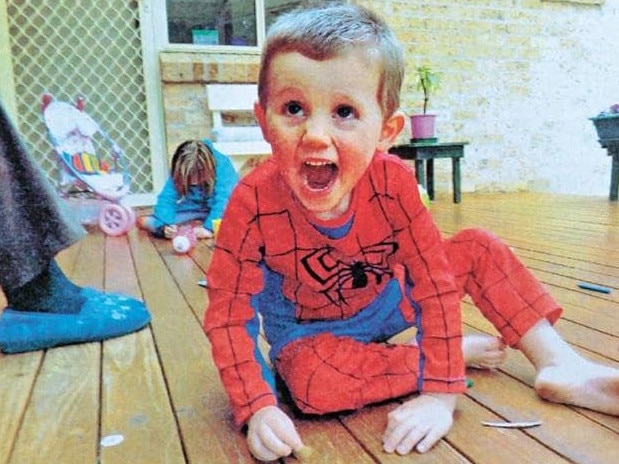

At 9.45am, William’s foster mother took three photographs of the boy.

The photographs capture William in a Spider-Man suit without his shoes on his grandmother’s veranda scattered with crayons.

As his foster mother would later remark, her last picture of William catches the young boy “mid-roar”.

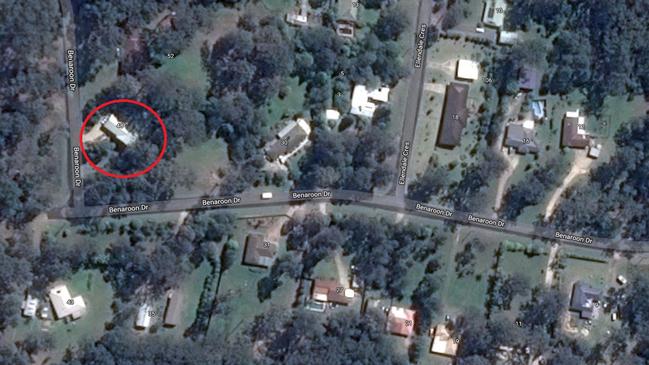

The grandmother’s two-storey, three-bedroom home sat on a corner block on a hill that looks back across the small estate comprising just 21 houses on Benaroon Drive and Ellendale Crescent.

Behind the substantial home, which has a long veranda across the back and sits on just under half a hectare of land, are trees giving way to thick scrub.

There was no cause for concern in this very small neighbourhood 20 minutes south of tiny Kendall town, with no lurking strangers, no break-ins or thefts.

Seemingly the only hazard was the weak mobile signal.

On that morning, William’s foster grandmother had reportedly expected a local repairman to drop by with a spare part for her washing machine and fulfil a quote made days earlier.

But he did not return on the day William went missing because he could not get in contact with her.

Houses on Benaroon Drive lie up to 20m from the front boundary, many with trees obscuring the line of sight from the road.

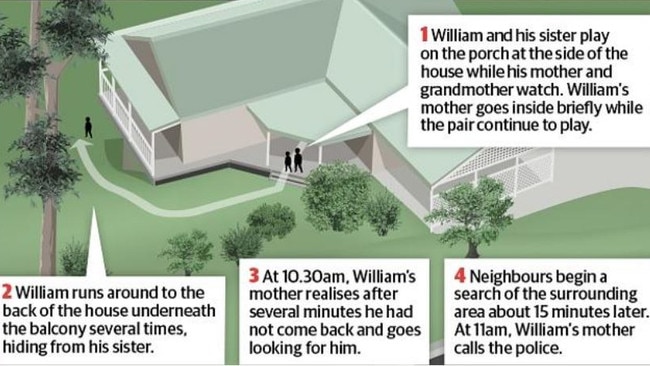

At some point after 9.45am, William was playing the lion game with his sister and had run to the back of number 48 and underneath the veranda several times.

On each occasion, he had emerged to his waiting sister with a cheeky grin.

Sometime before 10.30am, William’s foster mother retreated from the outdoors inside to make a cup of tea for her and her mother.

Down the street, a man on a ride-on mower cut his lawn.

Again, William disappeared down the side of his grandmother’s house towards the backyard.

Only on this occasion, the boy did not reappear.

When she noticed William was missing, his foster mother asked William’s four-year-old sister where he was and then ran back to the house and asked the grandmother if William was back up there.

He wasn’t and the two alarmed women conducted a further search, but William was nowhere to be seen.

Minutes later, neighbour Anne-Maree Sharpley was reading a book after dropping her children at school when she looked up and saw a woman frantically pacing the quiet street.

Soon, William’s foster mother had stopped at Ms Sharpley’s gate.

“You could tell she was very distressed when she first came to us,” Mrs Sharpley told The Sunday Telegraph.

“I just remember saying ‘Don’t worry, we’ll find him,’ and that has stuck with me because obviously they didn’t find him.

“I waited with her while she called the police.”

Neighbour Lydene Heslop heard a knock at her door, which she opened to Anne-Maree from up the road and William’s foster mother.

“The mother had this haunted look on her face,” Ms Heslop would later tell Australian Women’s Weekly.

Ms Heslop called to her children out back, but they hadn’t seen another kid. It was 11.30am.

“All three of us started searching through the front yard, the side of the house and the backyard and the bush that borders the properties around here.”

One of the women came to Paul Savage’s front door, screaming that William was missing, and he immediately joined the search.

“I went uphill by myself looking for him,” Mr Savage told news.com.au.

“I’ve gone up thinking he’s around here.

“We thought, he’s just run off somewhere, which is a natural thing and hopeful thing to do.

“There’s a track up through the bush. I walk up to there nearly every day.”

The small dirt track off Benaroon Drive winds through the bush for several hundred metres before it reaches a cemetery.

Soon, sleepy Benaroon Drive was chaotically alive with people.

William’s foster father had returned, crushing the foster mother’s faint hope that William might have run off down the road and caught up with him.

“There was a bit of confusion if William was with me, because he’s always looking out for me and my car,” the foster father said later.

“I was on my way back, and I’d arrived back and been asked if William was with me and I said ‘no’ then I immediately got out of the car and started looking round.

“Within five minutes we raised the alarm and I think I ran the perimeter of the street within about 10 to 15 minutes and I mean, he wouldn’t, he’s not a wanderer.

“He wouldn’t even cross the street by himself. He wouldn’t go far.”

Further down Benaroon Drive, the man who had been mowing his lawn said he was unaware of what was happening until, “I was on my ride-on mower and saw a police car”.

“Someone came running down the street,” he told Daily Mail Australia at the time. “They said someone had just lost a kid.

“I took my dog for a walk and had a look for him.

“I’ve been here the whole time, people have been pouring through our backyards. I really hope he’s found soon.”

The neighbour said he had met William’s father who was “searching through the backyards heartbroken and frantic”.

Just before 11am, the foster mother dialled triple-0.

Police arrived and called in the dog squad, followed by State Emergency Service volunteers.

By 1pm, a police helicopter was in the sky and with phones ringing hot around Kendall, soon scores of residents from surrounding areas had converged on Benaroon Drive to join in the search.

NSW Police began doorknocking houses in the Benaroon estate.

Judy Wilson returned from her errands in town to find the street in turmoil.

“The only thing I was able to tell police was that I heard the children playing but didn’t see them,” Mrs Wilson told The Sunday Telegraph.

“I just heard kids laughing and you could tell they were little children.

“I don’t think it was an opportunistic grab from someone who just happened to be here because we don’t get strangers wandering around.”

At 48 Benaroon Drive, police sniffer dogs picked up William’s scent, but only within the boundaries of the property.

Police searched each of the 21 houses in the estate, climbing into roof spaces, sub-floor spaces and wall cavities, and combing through cupboards, sheds and backyards.

Bushland surrounding the grandmother’s home was scoured, with no sign of William.

A little three-year-old in a Spider-Man suit could not have gotten far on his own, and police would swiftly conclude that William had been abducted.

After contacting NSW Family and Community Services to learn the details of William’s birth family, police knocked on a door in Sydney.

It was the home of 25-year-old Karlie Tyrrell and her partner, Brendan Collins.

William Tyrrell’s biological parents were interviewed, but police dismissed the pair as possible suspects in William’s abduction.

In Kendall, a shop owner would remember that a man had asked for directions to Batar Creek Road, which runs between the township and the spot from where William had vanished.

At Kendall Cellars, shop owner Rheannon Chapman was told not to delete anything from her CCTV.

As night fell on Benaroon Drive, no peace came with it.

Judy Wilson would later describe how William’s foster father frantically searched her yard, over and over again, into the night.

“He was just walking around crying. He kept asking me if there was anywhere else (William) could’ve been hiding here,” Mrs Wilson said.

“He just looked devastated.”

In the ensuing days, hundreds of tips and possible sightings poured in.

Search crews swelled to more than 200 police officers, SES volunteers and residents scouring properties and kilometres of bush.

Police divers arrived to search creeks and rivers.

On September 16, 2014, four days after William’s disappearance, volunteers came across a patch of blood near a creek just over 2km from Benaroon Drive.

Police brought in a forensics truck, but tests revealed the blood was not human.

On a bush track, a knife sheath and a set of small footprints were found, but police discounted them as a lead.

Lines of police and SES crews walked up and down hills.

They conducted “a more evidence-based search” of the Middle Brother National Park, 10km from the abduction site, looking for items like clothes possibly discarded from a vehicle.

Meanwhile the town of Kendall, with volunteers from up and down the mid-north Coast, swung into action, providing food for searchers and an online support network for William’s cause.

Judy Wilson’s husband, Richard, would later describe the Benaroon estate as “just a normal neighbourhood … we have had a couple of Christmas parties on the next door neighbour’s block and everyone is invited.

“But you don’t spend your life looking at what other people are doing,” he told the Newcastle Herald in late 2014.

With no trace of William, “after a week or two”, neighbour Paul Savage told news.com.au, “they got cadaver dogs”.

The houses in the Benaroon estate were searched a second and a third time.

Mid-north coast Superintendent Paul Fehon, in charge of the investigation into William’s disappearance, had his own frustrations.

Because child protection laws prohibit identifying children taken into care, William’s status as a foster child was shrouded in mystery and his foster family could not be identified.

Missing William’s family history was described as “complicated”.

Publicly his foster family could not be named, and therefore no grieving parents could front the media and beg for their missing child to be returned.

Nor could Karlie Tyrrell and Brendan Collins be named as William’s birth parents.

A “family friend”, Nicole, appeared with Supt Fehon as the human face of the unidentified family’s grief, but the effect was odd and unsettling.

Social media channels ran hot with discussions about William’s true family history; in some quarters it was an open secret.

On September 20, William’s foster parents issued a letter of gratitude.

The letter read, “Thank you does not seem like the right sort of word to express our gratitude and heartfelt warmth we feel towards each and every one of you.”

The following day, the physical search for William was scaled back.

Privately, the foster family endured an anxious Christmas.

The new year dawned, and on January 20, 2015, the nation woke to a major development in the case of missing William Tyrrell.

A police raid was under way at a house in the NSW mid-north coast town of Bonny Hills.

Detectives and plain clothes officers piled out of vehicles.

At nearby Laurieton, police searched a cabin at The Haven Caravan Park and a unit above a set of shops where they seized a mattress and computer equipment.

The Haven’s owner revealed a Victorian couple staying at the caravan park between September 28 and October 9 had heard a child crying in a cabin.

At the Bonny Hills home, an excavator and a septic service truck arrived.

The septic tank on the semirural property was drained, police sifted through mountains of bark on the grounds.

Strike Force Rosann, headed by the man who had investigated the long-running Bowraville murders case, Gary Jubelin, took over from Supt Paul Fehon.

Acting on a tip-off in early March, Detective Inspector Jubelin instigated a Homicide Squad search at Bonny Hills in dense bushland off the Pacific Highway.

But the search for evidence about 20km from William’s abduction point, uncovered little of any use and no charges were laid.

Homicide police soon revealed they were investigating a north coast paedophile ring.

Leading up to the first anniversary of William’s disappearance, Inspector Jubelin released details of two vehicles present in Benaroon Drive on the day in question.

The cars seen parked opposite by the boy’s foster grandmother were a dark grey, old-model, medium-sized sedan and an old white station wagon.

The car which drove past while William and his sister were riding their bikes in the driveway was described as a dark green or greyish-coloured sedan.

The strong community feeling for the missing boy was on show on the first anniversary of his disappearance on September 12, 2015, when 80 “Walk for William” events were held.

William’s foster parents released a Christmas poem to the media for the missing boy that December, and then in February 2016 posted on Facebook, begging people not to give up searching.

On the second anniversary of William’s abduction, the NSW Government established a $1 million reward, a state record, for information leading to his recovery.

In August 2017, almost three years since William had vanished, it was revealed the NSW Supreme Court had ruled statutory restrictions on identifying William’s “out of home” care status could be lifted.

The NSW Department of Family and Community Services had opposed an application to lift the restrictions, but Justice Paul Brereton found the matter was of “legitimate public interest”.

Justice Brereton also noted “the tragic probability that (William) is no longer alive”.

In June this year, Inspector Jubelin led a two-week search of Kendall and surrounding areas as a forerunner to William’s case being examined by the NSW Coroner.

More than 15,000 pieces of information and lines of inquiry had been collected since William disappeared.

Inspector Jubelin said his intention was “to prove that beyond reasonable doubt, William’s disappearance was the result of human intervention and not misadventure”.

During the search, Benaroon Drive resident and veterinarian Cheranne Garcia told Port News she wanted to block negative messages about her street.

“Our kids aren’t living in constant fear,” she said.

Her three children played in the bush and “never had any reason to be worried or concerned”. “My youngest still rides his bike into town,” she said.

Neighbour Paul Savage agreed, though he said Benaroon Drive has changed since William’s disappearance put the street on the national map.

The foster grandmother sold her house in 2016, but other residents of the once anonymous address have also sold up and moved, Mr Savage told news.com.au.

“We’ve lost different families,” he said, “(but) it still is a safe area.

“We spent a good week or two searching; it was a real community effort.

“The police were excellent in everything they did and they kept it up and kept popping back.

“(But) somebody somehow managed to get him and disappeared down the road.

“I don’t know how it happened of course. He’s been taken to a place unknown.

“It’s something you think about, but you’ve got to let it go, otherwise you’d go mad.”

The William Tyrrell inquest will take place in late March next year.