Leading voices against domestic violence say Baden-Clay decision is a slap in the face

THE bombshell decision to reverse Gerard Baden-Clay’s murder conviction is a huge slap in the face — but it could also be a gamechanger.

THE Queensland Court of Appeal’s bombshell backflip on Gerard Baden-Clay’s murder conviction is a slap in the face to victims of domestic violence.

That’s the opinion of family violence experts, support workers, and Allison Baden Clay’s own family, who are already personally pained by yesterday’s shock decision to downgrade her killing from murder to manslaughter.

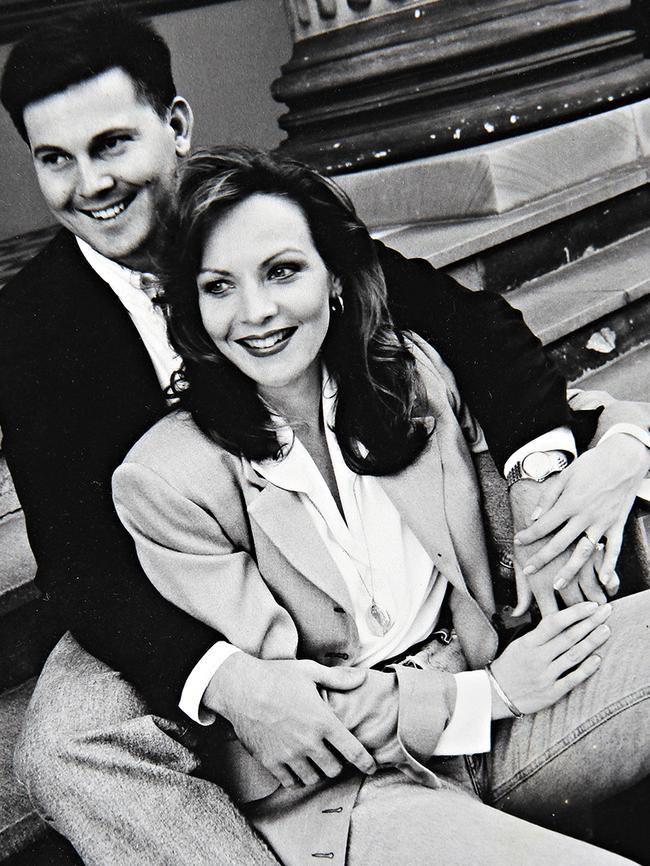

The ruling has prompted community outrage and scathing critiques on the state’s justice system, but no one is more disgusted than relatives of the Brisbane mum-of-two, who thought justice had been served when her husband was convicted last year of murdering her and dumping her body in a local creek. Baden-Clay, then a floundering local real estate agent, had been having an affair and was heavily in debt.

“I think the legal system that we are working with today fails a lot of women and children who are being killed and living in domestic and family violence,” Allison’s cousin told the Nine Network this morning.

“I think that really causes a lot of people who don’t or are not educated in domestic and family violence to not understand what is actually going on behind closed doors.”

President of Ending Violence Against Women Queensland, the peak body for domestic violence services in the state, agrees the Court of Appeal verdict does not send the right message.

“It does present a message to people in the community which makes them question, ‘Will the system support me?’,” she told news.com.au.

Ms Northey said she was disappointed with yesterday’s decision and understood the family’s disappointment, but suggested the attention the ruling has drawn presented an opportunity to reframe how the community views family violence.

Baden-Clay saw his murder charge set aside and substituted for manslaughter because three Court of Appeal judges found there was “a reasonable hypothesis consistent with innocence of murder”.

They decided it was possible that there was “a physical confrontation between (Baden-Clay) and his wife in which he delivered a blow which killed her ... without intending to cause serious harm”, and that therefore, Allison’s death may not have been premeditated.

But the way Ms Northey sees it, that shouldn’t matter.

“This legal decision opens up the discussion of how we view domestic violence as a community issue,” she said.

“My question would be if someone has been perpetrating domestic violence in a relationship, are they then culpable in recognising that could lead to someone’s death?

“For a woman experiencing long term historical domestic violence, there needs to be some recognition that there’s premeditation and that a perpetrator needs to be culpable in recognising that could lead to death. It is premeditated.”

Ms Northey proposed approaching domestic violence in the same way we view one-punch attacks.

“We know it can lead to death, examples like this highlight that, so perpetrators of domestic violence need to be culpable for what their actions may cause,” she said.

Speaking at a domestic violence symposium on the Sunshine Coast, Australian of the Year and family violence campaigner Rosie Batty said she was “gutted” by the Baden-Clay decision, the Sunshine Coast Daily reports.

“It absolutely sends the same message that I’m saying all of the time, that we undermine, disregard and disrespect a victim in a violent relationship,” she said.

“Why is it so hard to believe that when there’s a history of violence that the murder is intentional. Certainly I think that our whole judicial response needs a complete overhaul.”

Executive Officer of Rape and Domestic Violence Services Australia Karen Willis echoed calls for national discussion on domestic violence.

She said while her organisation and others understood there were complex legal systems in place in each state and territory, there needed to be consensus in some areas of dealing with domestic violence perpetrators.

“One thing that needs to be looked at is a difference in sentencing between assault or a murder that happens in a domestic situation to one that happen in another. It doesn’t matter what your relationship is,” she said.

She said including domestic and family violence as part of the national conversation was beneficial, but examples like Baden-Clay’s had the opposite effect.

“What we do know is that every time there is something in the paper that lays responsibility of violence with the offender and talks about the victim being not responsible, but brave or heroic and supported and successful in overcoming the violence, what happens is that a whole stack of other people decide ‘Yes, I can come forward and talk about this as well,” she said.

“When we get the opposite, it’s likely we’ll get the opposite result.”

Ms Northey said while the Baden-Clay case presented an opportunity to open debate on the issue, she hoped it wouldn’t discourage other women seeking help.

“Our goal is always to look for justice for women and the question would be has justice been served in this circumstance,” she said.

“The message that needs to get out there is that domestic violence perpetrators are taking a risk that could lead to murder, not a message to women that there’s no culpability.”