Inside the William Tyrrell inquest

Inside the William Tyrrell inquest was a room divided, with the biological family on one side and the foster family on the other.

The case of missing William Tyrrell is the mystery everyone but the perpetrator wants to solve but when the inquest opened this week, the room was divided into two distinct camps.

Three-and-a half years after the three-year-old disappeared from Benaroon Drive, Kendall, on the NSW mid north coast, they gathered 350km south in the shiny new concrete and glass Coroner’s Court at Lidcombe in western Sydney.

Inside Court One, sitting on the left hand side of the room was the working class biological family.

William’s birth father, his half brother, the missing toddler’s grandmother and a band of supporters attended every day.

They included child protection activist Allanna Smith, a one-time foster child herself.

Ms Smith led the successful court bid against the Department of Family and Community Services that lifted the veil of secrecy over William’s status as a foster child.

On the right side of the court were the more well-to-do foster parents and their supporters.

Two ladies handing out “whereswilliam.org” ribbons, in blue and red Spider Man suit colours, sat with them.

Conducting the inquest was NSW deputy state coroner Harriet Grahame, but steering it was counsel assisting, Gerard Craddock, SC.

The counsel assisting was more like a Sunday school teacher than the customary smiling assassin prosecutor forensically extracting the evidence.

He asked questions about how cups of tea were poured before William vanished, how thick the lantana scrub was and how steep were the fire trail was.

The aim of this preliminary week of the inquest, which will resume in August, was to provide background to William’s birth and foster families, his disappearance and the massive search.

Lined up on the bar table was a bank of lawyers representing everyone but the birth parents.

The foster parents had two lawyers, the FACS department one senior counsel instructed by the Crown Solicitor.

A lawyer for the Salvation Army, which had co-supervised with FACS some of William’s fostering, sat by two lawyers representing a neighbour and a washing machine repairman.

Why the two men, who are neither suspects nor “persons of interest”, needed lawyers was unclear.

The biological family had no lawyer and most of them had no protection from the glare of the media, other than non-publication orders that have suppressed the names of all families, foster and biological.

They went in and out through the front door.

The foster parents entered and exited via a private side door, and drove out in the back of a relative’s car covered in a blanket.

When one cameraman tried to film them, he was admonished by court officials and the breach was aired in the courtroom and damned by the coroner.

Only on the inquest’s final day was the birth mother smuggled through the entrance used by the foster parents.

The inquest’s first week might just be the precursor to a fuller, four-week inquiry in August.

But it was the strangest inquest I’ve ever attended, a walk in the park rather than inquisitorial, as probative as a pillow.

It failed to shed much light on William himself: what kind of little boy was he?

We learned he wasn’t a wanderer and didn’t like climbing, but even three-year-olds have personalities.

Amid the descriptions of tea drinking and lantana, no picture of William emerged.

After lunch on day one, Mr Craddock, a shortish balding man in a grey suit, briefly and gently took the foster mother through her family’s early acquisition of William and his sister.

They had visited her parents’ house at Benaroon Drive several times with the children, so that she had sought a “bulk approval” for visits, as required by the Salvation Army case worker supervisor.

We heard much about the fact William’s last trip to Kendall was contingent “on being able to get the cats into boarding”, and about her mother’s broken washing machine.

Referred to as “Nanna” by Mr Craddock, the foster grandmother was not called as a witness this week.

The foster mother spent several hours in the witness box, tearfully remembering William’s last morning.

Mr Craddock walked her through the morning’s games with William and his sister, a “mummy monster” game with the foster mother and a “daddy tiger game” on his own.

Then there were the strange cars, three of them, she remembered in the street that morning.

The foster mother explained she hadn’t remembered cars in the street until days later, when she recalled seeing two dirty old cars without hub caps.

Curiously, they had tinted side windows, so you couldn’t see through them, and they were parked between driveways, which just didn’t happen on Benaroon Drive.

The third car, a “greeny teal looking” car without tinted windows had been in motion, driven by a man she got only a “fleeting” look at but who had given her a knowing glance.

She described him as “thick-necked”.

“He was sitting back from the steering wheel,” she said.

“He was a big man … late fifties, a man who has been in the sun a long time, that old weathered look.

“I can still as I am talking to you … see him.

“I am firm I saw that man; that car was there.”

The foster mother said the car was old with “aged white paint … alloy wheels that didn’t have hub caps, you could see the spokes, silver on the outside, the middle hold, brassy-looking”.

Mr Craddock asked for further details of the man’s hair colour, length, complexion, ethnic origin, whether he was tanned, had a beard or glasses.

The foster mother said the man had short, reddish hair, no facial hair or glasses, was caucasian, and not overly tanned.

In his opening address, Mr Craddock, told the court William had disappeared while the foster mother and Nanna were drinking tea that was still warm or “not too cold to drink”.

He remarked there were different ways of making or pouring tea and asked the foster mother what was hers or her mother’s preferred way.

We learnt that Nanna likes her tea a bit weaker, and so it was the two were drinking, William was playing a new “daddy tiger” game and then it all fell quiet.

Weeping, the foster mother recounted how she heard William’s last roar, then “nothing” and how she raced around looking for him thinking “he’s not brave enough” to go off hiding.

At the end of day one, the foster mother came off the stand and was embraced by the foster father in court, but continued her testimony into day two.

She told the court Nanna had thought William too “hyperactive, boisterous” in his play immediately before he vanished.

When the foster father returned from nearby Lakewood and the Kendall shops, and was told about William, he “bolted … running for William and I didn’t see him for ages after that”.

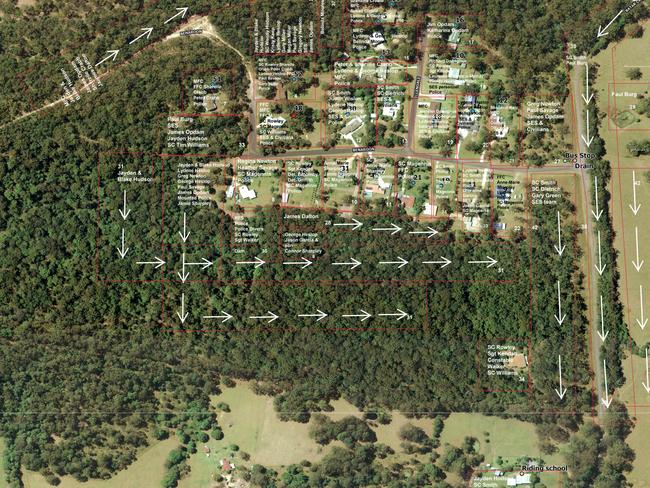

The coroner, Harriet Grahame, was very careful to thank neighbours, police and State Emergency Service officers who helped in the massive search for William, which went on for days.

Lydene Heslop, a mother of small children, had swung into action early, put William’s name on Facebook and lured local friends into joining in the ground search.

At the end of the day, the “Kendall born and bred” local fired up the family food truck and fed the weary searchers.

Another neighbour, Anne Maree Sharpley, had been having a quiet smoke after taking her youngest child to daycare when the foster mother had come to her door.

Ms Sharpley helped the foster mother search up and down the street.

After the Coroner thanked both Ms Sharpley and Ms Heslop for what they had done, the foster mother went up to the two women in the court to thank them too.

On Wednesday, the NSW Justice Department informed media the foster father’s evidence would be delayed, then reversed the decision.

The foster father, who works in sales, could be seen limbering up in court rooms in his pink business shirt and skinny jeans, twisting his square toe shoes and breathing deeply.

He told the court he had met the foster mother about 2006 and as a motorcyclist he had ridden his trail bike around the Kendall State Forest “extensively”.

He explained away his frantic behaviour after arriving home and tearing off to run like a madman up hill and down dale without finding where his wife had already searched for William.

“There is method in my madness,” he said, “I thought it was probably better for me to branch out … outside the house.”

The foster father was in the witness box barely more than an hour, which left some observers unsatisfied, and wanting to get more of an insight into him and William.

On the hearing’s final day, two local police officers took the stand.

Senior Constable Wendy Hudson had been on her rostered day off at the Kendall Tennis Club when she heard about the missing boy and joined the search with her two teenage sons.

Sen Const Hudson managed to speak with William’s sister about whether the boy had hiding places.

“I wasn’t tough with here, but I had an opportunity to speak to her,” Hudson said.

“There were no hiding places.”

Asked by Mr Craddock if the foster father and foster grandmother’s vehicles had been searched, she said, “not be me”.

Gregory Newton then took the stand, a tall man with a full head of white hair, who resembled country singer, Charlie Rich.

Mr Newton’s brother-in-law and late sister lived directly across from the house where William vanished.

Mr Craddock asked him about where his brother-in-law was standing on Benaroon Drive before the two men joined in a line search.

He told us that Mr Newton’s son played for the Coffs Harbour Snappers rugby union team, and that he was staying in Kendall with his sister to see the boy play.

After walking Mr Newton through a line search, a barking dog and, yes, the thickness of lantana, Mr Craddock quipped, “I think the Snappers lost?”

“They did,” Mr Newtown replied and chuckled, along with others in the court.

The final two witnesses were William’s biological mother and father.

Outside the courtroom, anti-fostering activist Allanna Smith said with the hearing winding up, she didn’t believe much light had been thrown on young William.

“It seems they don’t want to paint a picture about his life in foster care,” she said, asking why the foster grandmother, the only other adult present when William disappeared, was not at the inquest.

“It’s been a storytelling exercise rather than a fact finding one.”

Ms Smith also believed there was an imbalance inside court one, favouring the foster parents over the birth parents.

She said the biological grandmother was not told she could get legal aid to have her son and former de facto daughter-in-law legally represented.

“It’s not a matter of whose fault that is, it’s a matter of justice, fairness and due process,” she said.

“The biological parents are up next and essentially are doing it on their own.”

William’s biological mother took the stand, dissolving into tears as she told how FACS had taken him from her when he was nine months old.

This was after a five or six week period when she and the birth father had hidden William so FACS couldn’t take him off into foster care.

Mr Craddock had withdrawn as the questioner, replaced by his assistant, Tracey Stephens, whose style was sharper, more demanding.

Tracey Stephens: “You and the father absconded with William?”

Birth mother: “Yes.”

Stephens: “You knew you weren’t allow to do that?”

Mother: “Yes.”

Asked about when the game was up and FACS found her and the birth father, and then took William, she said she had not given up on William.

She attended every bimonthly visit, requested more contact and pursued the few paths birth parents have when their children are taken by FACS.

“I’d send emails, call the ombudsman,” she told the court.

The last time she saw her son was on August 21, 2014, at a Chipmunks Play Centre in Sydney.

During this part of her testimony, as had other witnesses, the birth mother referred to people by name whose names were suppressed and was warned by Ms Stephens and the coroner.

“Oh sorry,” she said, and then with her hands in the air, “I’m so confused.

“They all know our names. What’s the big deal? I’ll lose it.”

Ms Stephens read out the birth mother’s statement to police when asked if she had kidnapped her son.

“I definitely didn’t take William. If I took him I would be gone.”

The birth father took the stand.

A slight man, with short dark brown hair, a thin face and a soul patch, he spoke softly and was told by both the coroner and Ms Stephens to speak up.

Like his former partner, legally unrepresented, the birth father had nevertheless clearly been thinking about what he wanted to say.

His statements about not having a normal life, about how “in the end I broke down, I lost it” appeared to refer to his life after William’s disappearance.

Ms Stephens repeatedly told him to answer her questions.

He told her “I am still waiting to be informed” about what happened to William.

Asked if he received information about William’s whereabouts whether he would tell police, he replied, “Most definitely”.

Ms Stephens asked him about the Salvation Army welfare workers attending his and the birth mother’s home after William vanished.

The birth father responded, “When the tables were turned, they weren’t the ones on my side.

“They f***ed up.

“The minister had a duty of care to keep him safe until he was 18.”

The inquest has wound up for now, with the coroner saying it would sit for four weeks later this year.

The four days of hearings was described as “the tip of the iceberg” compared with the later hearings, which would star “persons of interest”.

Outside, Allanna Smith stood by the side of William’s biological grandmother.

The grandmother said hearings had been “upsetting” and she was “very overwhelmed”.

But she felt her son and the birth mother had been treated less fairly than the foster parents.

Allanna Smith described the inquest so far as a “fishing expedition”.

And if that was the case, no whoppers were caught.