‘How could this happen?’: Indigenous teen’s death in custody probed at inquest

The death of a sixteen-year-old boy in an adult prison is being probed during a lengthy coronial inquest.

On the night a teenager became the first child to die a self-inflicted death in custody in Western Australia he threatened to take his own life eight times and custodial officers managed several other detainees who self-harmed or threatened to self-harm, an inquest has heard.

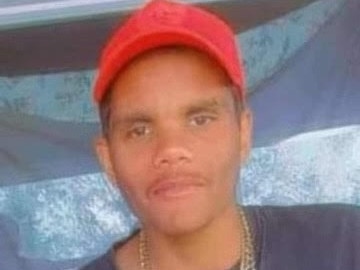

Cleveland Dodd, 16, died in October last year after he was found hanging in his cell at the infamous Unit 18, attached to the maximum-security Casuarina Prison for adult men.

An inquest into Cleveland’s death began in the WA Coroner’s Court on Wednesday.

Counsel assisting Anthony Crocker told Coroner Philip Urquhart that Cleveland’s death was the first known death of a young person by apparent suicide in a youth detention facility in WA.

Cleveland had a history of threatening to harm himself and at 13 years of age “Cleveland’s life was deeply unsettled” as he had been in and out of watch houses and WA’s lone youth detention centre Banksia Hill, the court heard.

“On five different occasions, after being arrested, Cleveland tried to hurt himself in WA Police custody,” Mr Crocker said in his opening address.

When he was 14, a neuropsychologist found Cleveland’s emotional and behavioural difficulties were caused by early life trauma, limited language abilities, exposure to family violence, cannabis withdrawal symptoms and an anti-social peer group.

A host of recommendations from the psychologist were made, such as mental health support, seeing a regular GP, and returning to school, but Mr Crocker said few if any of those recommendations happened.

Cleveland was bounced between the youth detention centre and Unit 18 — a centre for hard to manage youth detainees. He was put there one time for climbing onto a roof at Banksia Hill.

Six months before his death, Cleveland’s uncle died and the teenager was unable to go to the funeral. He spent various periods with an internal ‘youth at risk management system’ designation.

“The consistent view expressed in mental health assessments and risk assessments undertaken in detention for Cleveland was that he did not plan or intend to harm himself, or complete suicide, but rather that he used self-harm or threats of self-harm to have his needs met, or as a way of expressing his distress,” Mr Crocker said.

Cleveland was taken off the ‘youth at risk’ 10 days before he took his own life, in part because of a record which showed he had not self-harmed for 11 days.

On the night he took his own life, Cleveland repeatedly told staff via the intercom he would hurt himself, apparently sparked by various issues such as another detainee self-harming, Cleveland’s neighbour making noise and Cleveland himself being refused water.

Mr Crocker told the inquest staff and the detainees did not know about a planned power outage the night Cleveland took his own life, and one staff member was reclining in a dark office, not fully dressed when Cleveland was found.

Unit 18’s radio was not on, nor were the youth custodial officers carrying radios.

How the death of a child occurred in a facility designed and built for maximum security men begged the question “how could such a thing happen?” Mr Crocker said.

Cleveland died in hospital one week after the incident.

Oral evidence from the youth custodial officers and the prison duty nurse is expected to begin on Friday, and continue next week.

The inquest is scheduled to then be adjourned until July, when the senior officer on duty that night, superintendent of Unit 18 and medical professionals who treated Cleveland are expected to give evidence.

In total, the inquest is scheduled for 21 sitting days.