Chris Dawson guilty of wife Lynette’s murder as motive revealed

After a marathon five-hour judgment, a judge has found Chris Dawson had three motives to kill his wife Lynette.

Justice Ian Harrison SC has found Chris Dawson had three motives to kill his wife Lynette, finding him guilty of her murder after a marathon five-hour judgment.

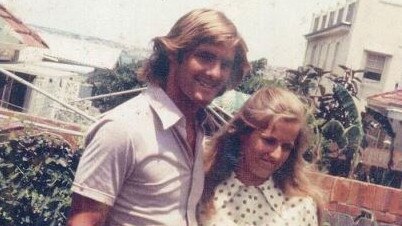

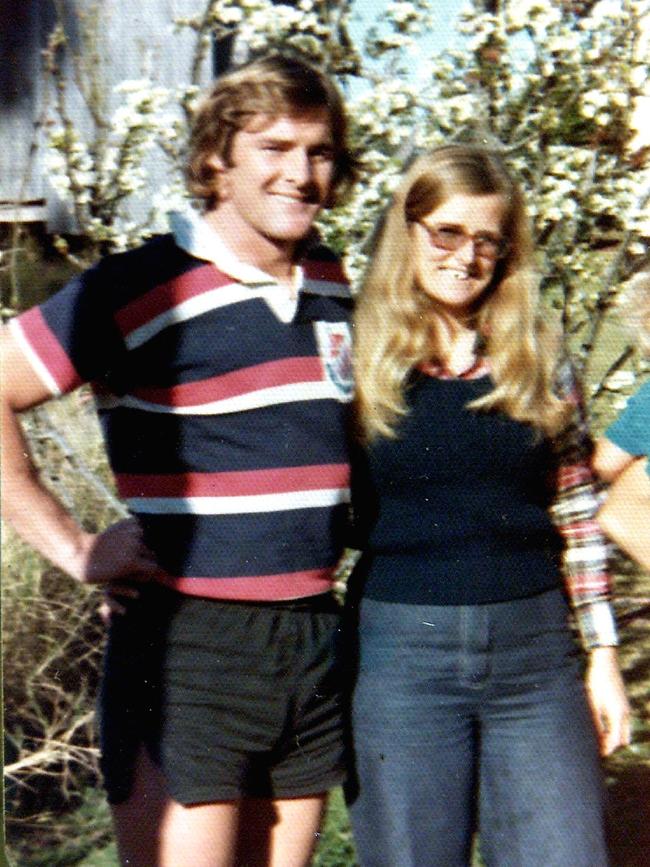

The former teacher and rugby league player was accused of killing his wife to be with the family’s teenage babysitter, known as JC throughout the trial.

Justice Harrison agreed with the crown’s argument that Dawson had a deep animosity to his wife, wanted “unfettered” access to his teenage lover and was determined to avoid the financial implications and custodial arguments of a divorce.

Delivering his findings on Tuesday afternoon, Justice Harrison said JC’s desire to end their affair had pushed Dawson to kill his wife.

“I am satisfied that distressed, frustrated and ultimately overwhelmed and tortured by her absence up north Mr Dawson resolved to kill his wife,” he said.

The judgment follows earlier rulings that Ms Dawson had died on or around January 1982, and a claim that she left the family home voluntarily was not true.

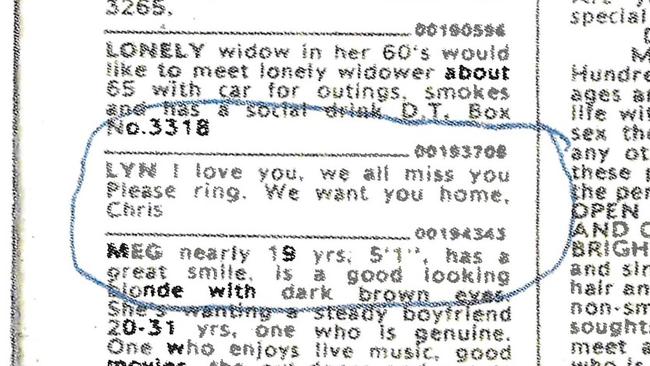

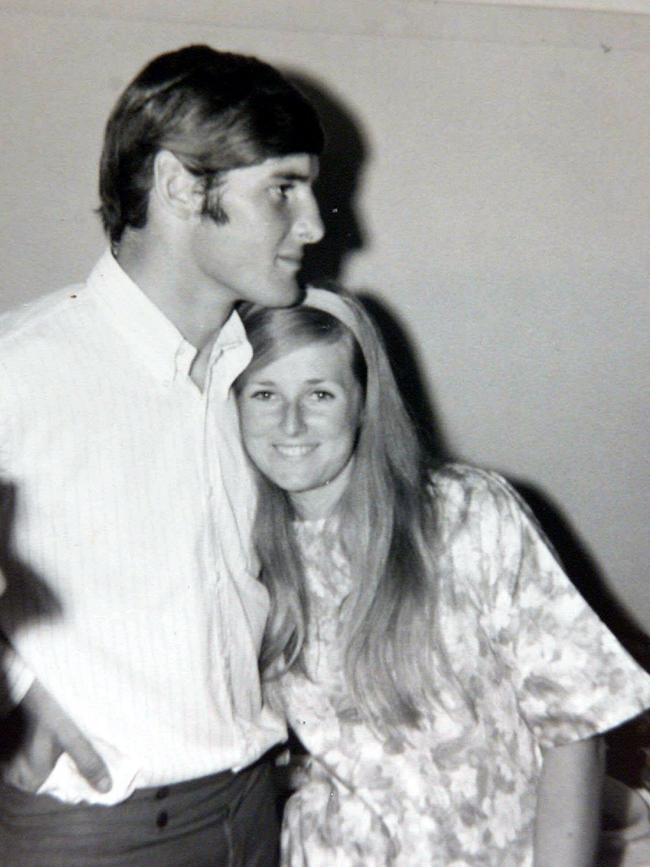

Ms Dawson mysteriously vanished from the family home in Bayview in the summer of 1982, just weeks after her husband had unsuccessfully tried to run off with the babysitter.

The 33-year-old nurse was last seen on Friday January 8, 1982, when she spoke to her mother on the phone. She was never seen or heard from again, and her body was never found.

Police alleged she was killed either Friday evening or early the following morning.

Dawson has always maintained his innocence.

Dawson fought the murder charges in a sensational 10-week trial before Justice Harrison, with sordid details of his relationship with JC front and centre of the claims.

JC was one of Dawson’s former students who came to live with the family and care for their children in 1981 in order to escape her own turbulent home life.

The Crown argued during the trial that one of three motives Dawson had to murder his wife was a desire to have an “unfettered” relationship with JC.

“The heart of the Crown’s circumstantial case is said to be Mr Dawson’s very strong motive that flowed from what it said was his utter infatuation with JC and his desire to be with her,” Justice Harrison told the court on Tuesday.

The court was told that JC and Dawson first had sex at his parents’ home in 1980, well before Ms Dawson’s disappearance.

JC told the court that she regularly had sex with her former teacher while his wife was asleep or in the shower and claimed Dawson regularly fed alcoholic drinks to his wife that would make her fall asleep.

Justice Harrison said Dawson and JC were in an “energetic sexual relationship” before and after his wife’s disappearance, and Dawson was “obsessed” with the teenager and the prospect that she would leave him.

He said the intense relationship between the pair and Dawson’s fear of losing JC was “not by itself sufficient to establish the crime”, but he was satisfied beyond reasonable doubt that Dawson’s intent was to leave his wife for JC.

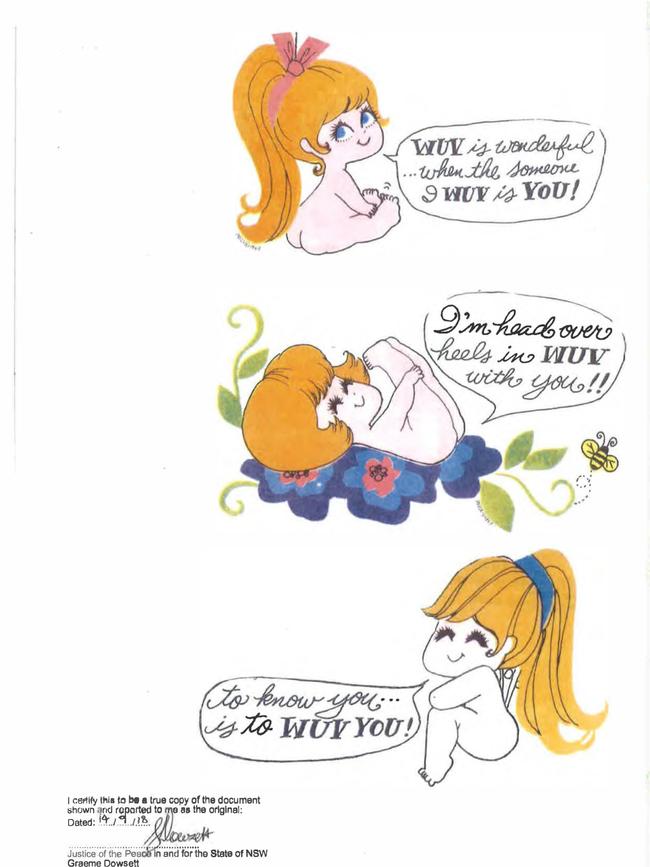

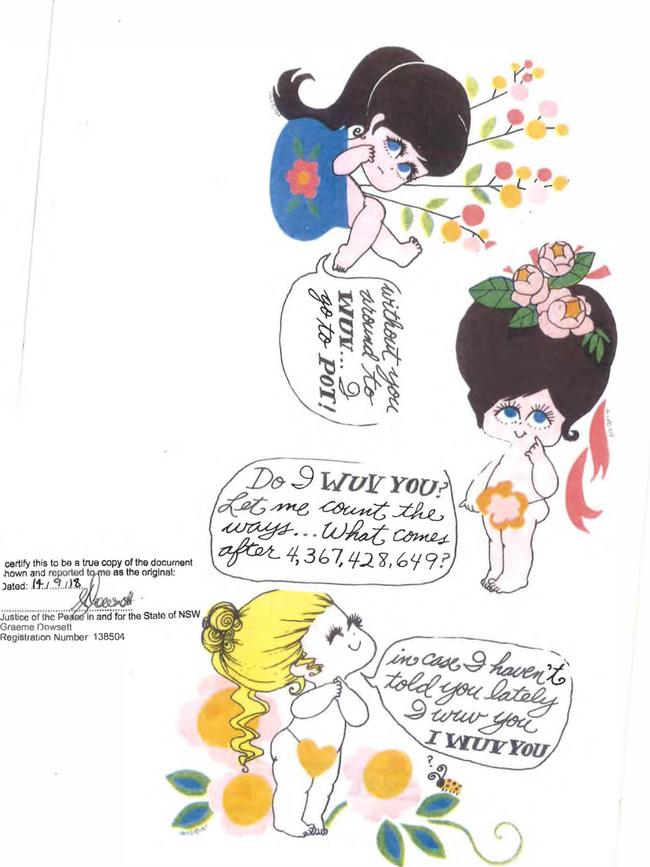

Notes from Dawson “professing his love” to JC were tendered to the court during the trial, including a Christmas card that suggested she would one day be his wife.

Justice Harrison said he accepted the Crown’s argument that Dawson “became infatuated with JC before she left school”.

Justice Harrison also accepted a claim that Dawson had threatened a 16-year-old boy, known in the trial as PS and who worked with JC at Coles, to stay away from her.

In late 1981, Dawson and the babysitter packed a car with their belongings and set out to move to Queensland.

The couple didn’t make it to Queensland, instead turning around when JC felt ill. JC and Dawson spent Christmas Day 1981 at his brother’s house.

A few months later, in early 1982, the babysitter told the court that she received a call from Dawson telling her “Lyn’s gone, she’s not coming back”.

JC married her former teacher two years later, but the couple bitterly split after six years together.

Justice Harrison found JC’s evidence to the court to be “truthful and reliable” and said he did not believe the couple’s acrimonious break-up had tainted her evidence.

In 1990, JC claimed Dawson had contemplated hiring a hitman to kill his wife but had refrained because, as she told the court, he said “innocent people would be killed, could be hurt”.

Justice Harrison said he was “not able to be satisfied” about this claim.

Dawson’s defence team had argued during the trial that his relationship with JC had pushed Ms Dawson to leave of her own accord.

When ruling against this, Justice Harrison told the court the mother of two was dependent on her husband to drive her everywhere, had only about $500 in cash at the time, and crucially, had left her beloved children behind.

None of her personal belongings appeared to have been taken from the home, which Justice Harrison suggested was “unlikely” in the event Ms Dawson had left of her own accord.

An extensive attempt by police to find Ms Dawson had found “no trace” of her.

Justice Harrison said Ms Dawson had not been seen or made any contact with family or friends and noted there was no record of her holding an Australian passport or drivers licence, being registered with Medicare or the Australian Taxation Office, and she had not been identified in any discovered human remains.

He also noted that despite huge national and international interest in the case, no one had ever come forward to suggest she was alive or confirm she was dead.

Dawson had maintained he dropped his wife off in Mona Vale on January 9 and she was meant to meet him at Northbridge Baths later but had instead called him to say she needed time to herself.

Justice Harrison found there was “no truth” to the claim.

He told the court: “I’m satisfied beyond reasonable doubt that Mr Dawson’s reported telephone calls with Lynette Dawson after 9 January 1982 are lies.”

Justice Harrison also labelled the idea that Ms Dawson would call her husband and nobody else after disappearing – referencing a claim Dawson had made to police that his wife had contacted him after going missing – “absolutely absurd”.

Dawson was silent as he walked into the Sydney Downing Centre on Tuesday morning to hear the judge’s final decision. He was supported by his lawyer and elder brother as he walked through the tight crowd of journalists reporting on the case.

Ms Dawson’s family and supporters arrived at the court alongsideThe Australian journalist Hedley Thomas, all wearing pink in her honour as they awaited the verdict after 40 years of wondering what happened.

The courtroom overflowed with journalists and interested court watchers, many of whom were directed to a nearby screen where the verdict would be broadcast to those who couldn’t be accommodated in the room.

But Justice Harrison said even after Dawson and JC had left together, Ms Dawson told others that she was “waiting for her Chrissy to come home” and was speaking of him in “affectionate tones” just days before Christmas.

She “adored her husband”, he said.

Mr Dawson’s defence team argued that Ms Dawson was alive after her disappearance.

They relied on five sightings in the two years after she vanished by people who knew her, including the Dawsons’ former neighbours, Dawson’s brother-in-law and family friends.

The defence argued that Ms Dawson had willingly abandoned their northern beaches home and her children, who never heard from her again.

In Justice Harrison’s judgment, he said he found that “none of the alleged sightings were a genuine sighting of Ms Dawson”.

One witness had told the court that Ms Dawson had told him she was planning to run away from her marital problems.

Justice Harrison ruled the mother of two was dead and had not left her home of her own accord.

“Lynette Dawson is dead … she died on or about 8 January 1982 and she did not voluntarily abandon her home.,” he told the court.

The court heard evidence from Ms Dawson’s colleagues and friends that Dawson was physically abusive and despised her.

Tuesday’s decision marked the eagerly anticipated conclusion of a captivating murder trial that bore all the twists and turns of a Hollywood film plot.

The case of Ms Dawson’s disappearance had gone cold, but it was revived after an award-winning podcast called The Teacher’s Pet sparked international interest.