Australia’s 1960s concrete buildings are under threat, but are they worth saving?

THEY’RE big, grey and some say ugly. Australia’s 1960s concrete constructions divide views. But in our rush to rebuild are we bulldozing our best buildings?

TO SOME they’re eyesores, to others a sight for sore eyes. But whether you love or loathe big, brooding 1960s buildings, what’s not in dispute is that in Australia they’re under threat.

Battle lines have been drawn pitting preservationists, who want to see the structures survive, against developers — and even the odd former prime minister — who want to tear them down.

The most famous structure built during the sixties in Australia, perhaps the world, is the Sydney Opera House, which gained UNESCO heritage listing in 2007.

But other buildings of the period have been less enthusiastically embraced with Brisbane’s Law Courts, built in 1968, demolished this year.

Sydney’s Sirius building — revered and reviled in equal measure by the thousands who pass it every day as they cross the Sydney Harbour Bridge — came one step closer to the wrecking ball earlier this week.

Looking like a child might have constructed the building from giant Lego bricks — if every block was grey — the NSW Government's family and community services department has recommended its demolition although the final say lies with the planning minister.

Leading the charge to save these beauties of brutalist architecture is the National Trust’s advocacy director Graham Quint who nominates the High Court of Australia in Canberra and Melbourne’s National Gallery of Victoria as prime examples of the form.

He admits it’s no easy task to persuade people they are more than ugly carbuncles.

DRAMATIC BUILDINGS

“They’re dramatic and they’re meant to make a statement,” Mr Quint told news.com.au. “I don’t know whether beautiful would be the word, but not everything’s meant to be beautiful.”

The Sirius building had a unique history, said Mr Quint, built specifically for housing commission tenants turfed out of harbourside suburbs when the area was being redeveloped in the 1960s. Plans are afoot to replace the building, which most tenants have now moved out of, with apartments sporting million-dollar views and price tags to match.

Far from blocking views of the harbour it actually “steps down” to reveal a wide sweep of Sydney, said Mr Quint. Any replacement could be even bigger.

With older buildings now largely protected, more modern buildings were in developer’s sites, he said. But in some cases, concrete constructions were coming down simply for aesthetic reasons.

The 87m high Sydney Ports’ harbour control tower, built in 1974 and nicknamed “the pill” when it controlled all the berths along the city’s waterways, became redundant in 2011. It now lies at the heart of the multi-billion dollar Barangaroo redevelopment of the city’s disused commercial port.

“It’s probably the last remnant of maritime Sydney, it’s in good condition and it earns $100,000 in rent from the transmission towers so it pays its way,” said Mr Quint who advocates for its reuse as an observation deck or the centrepiece of a new museum dedicated to the harbour.

A very powerful voice wants to be rid of it, though. Former prime minister Paul Keating is a driving force for the new Barangaraoo Reserve where the tower rises and in December told Fairfax that the tower “does not have a shred of heritage about it”.

A spokesman for NSW heritage minister Mark Speakman told news.com.au nine buildings from the era had been heritage listed in the past two years but the tower did not “demonstrate aesthetic characteristics in a way that is of state significance” and was “incapable of reasonable or economic use”. In July, the NSW Government gave the site’s owner, the Barangaroo Development Authority, the green light to tear the tower down.

A spokesman for the authority said revenue from the tower’s mobile phone masts “helped offset maintenance costs” and that they remained committed to removing the structure “as soon as is reasonably practicable”.

Victorian opposition leader Matthew Guy is also a vocal critic of brutalist buildings.

In 2014, when he was planning minister, he said, “I don’t think we should be saving ugly buildings in Melbourne”.

But Mr Quint said he was concerned that in decades to come, the country might regret its demolition frenzy.

“It seems to be a thing in Australia to demolish and build again and you can end up losing a whole period of architecture for no good reason,” he said.

SAVE OR SACRIFICE?

Australia Square, Sydney

Designed by renowned Australian architect Harry Seidler, this 1964 building is arguably one of the country’s most iconic skyscrapers. Perfectly cylindrical, visitors continue to flock to its revolving bar and restaurant for 360-degree panoramic views across the city.

Total House, Melbourne

Built in 1965, this quirky building features an office block precariously perched on top of a car park. In 2012, a developer proposed to tear it down and build a 70-storey hotel. Campaigners successfully applied for heritage listing and the offices are now a favourite with architects and designers.

Sydney Masonic Centre

Passers-by could be forgiven for thinking this riot of concrete was all built in the mid-1970s. But the distinctive tower, which seems to defy gravity teetering on a point, was only added in the mid-2000s to complement the original building below.

National Mutual Life Centre, Melbourne

One of the city’s first brutalist office blocks, the building was originally trimmed in gold and marble. In 2014, it was torn down after unsuccessful attempts to save the structure.

High Court of Australia, Canberra

Suitably sober and stern, the design of Australia’s most important court building seems to reflect the decisions made inside. The 1975 building is heritage listed and was designed by the same architects as the nearby National Gallery.

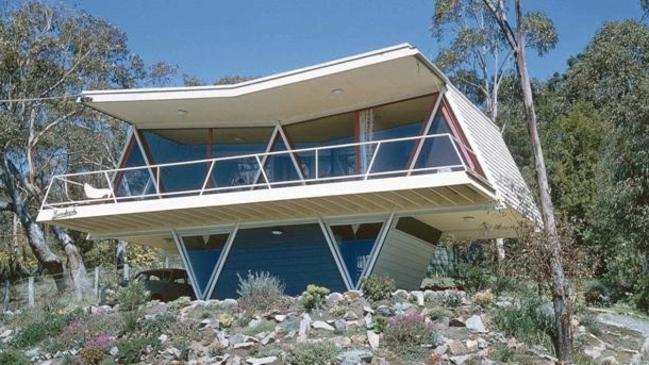

McCraith House, Dromana, Victoria

The National Trust awarded a heritage award for restoration and refurbishment works at this brutalist landmark home.