Australians would support changes to organ donor registration system

A liver transplant at nine months changed Anthony Schiller’s life, allowing him to walk, then run, then become the youngest competitor at this year’s World Transplant Games.

The majority of Australians want the ability to register as organ and tissue donors when renewing or applying for their driver’s licence, new research shows.

Six in 10 respondents to a YouGov poll were in favour of having this power – which is supported by the nation’s Organ and Tissue Authority – with backing rising to 71 per cent among Baby Boomers.

Only South Australian residents currently have this option and DonateLife figures show the state has the nation’s highest registration rate of 72 per cent. Seven in 10 SA families are also saying ‘yes’ to their loved ones becoming donors when asked in hospital.

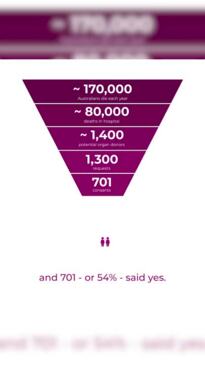

These figures are well above the national averages of 36 per cent for registration and 54 per cent for family consent.

The OTA aimed to have 50 per cent of people aged 16-plus on the Australian Organ Donor Register and a 70 per cent national consent rate in five years’ time, chief executive Lucinda Barry said.

This would result in an estimated 300 more people per year receiving lifesaving and life-changing organ transplants.

“To achieve that, we need to make sure people can register easily,” Ms Barry said. “The evidence from SA shows one way of achieving that is through driver’s licences.”

In 2022, 1224 Australians received organs from 454 donors.

Fifty-seven per cent of respondents to the poll of 1025 people were also in favour introducing an opt-out system where all people are presumed to consent to organ and tissue donation, unless they specify otherwise.

Changes like these are being considered in Victoria and Western Australia, as the states undertake parliamentary inquiries into the effectiveness of the current system.

The OTA – which has provided submissions to both inquiries – says an opt-out system would not be a “silver bullet” for boosting donations.

“The perception that opt-out means there would be thousands more donors (is) not true,” Ms Barry said.

“Only 2 per cent of people who die in Australian hospitals die in a way they can be considered for donation. In 2022, that was only 1400 people.

“And regardless of whether we’re opt-in or opt-out, families will always be asked to consent to donation. In opt-out systems across the world (including in Spain and the UK), if the family objects, donation won’t proceed.”

OTA national medical director and senior intensive care specialist Helen Opdam said for families asked to consent to donation, knowing their loved one wanted to be a donor was “incredibly important”.

“The big problem is families not knowing what their relatives wanted,” Associate Professor Opdam said. “Having a system where people can easily opt in, such as through their driver’s licences, is so helpful to that conversation.”

All four UK nations have introduced opt-out systems over the past eight years, while retaining the ability for people to opt-in.

Representatives of the UK’s National Health Service told Victoria’s parliamentary inquiry this week that the countries were still seeing significant opt-in registrations – up to a million a year – following the change.

Assistant director for organ donation John Richardson said the first UK nation to introduce opt-out, Wales in 2015, launched the new system with a “comprehensive media campaign and household mail drop”. Wales’ family consent rate increased in the years to follow, but Covid had since negatively impacted consent across the UK.

“Potential organ donors who have an opt-in registration still represent our highest rate of consent, about 90 per cent,” he said.

“The bulk of our opt-ins come from people renewing their drivers’ licences (73 per cent in 2022).”

The YouGov poll also reveals seven in 10 Australians mistakenly believe not everyone can register to be a donor – particularly those who have had cancer, smoke or drink or are generally unhealthy – and three in 10 don’t know how to register.

“It doesn’t matter how old or unhealthy you are,” Dr Opdam said. “Anyone aged 16 and above, please register and leave it up to the health professionals to determine whether you’re suitable to become a donor.”

Australians can register at donatelife.gov.au or via the Medicare app.

From transplant baby to gold medallist

The change in nine-month-old Anthony Schiller after his liver transplant was almost instant.

His swollen belly went down and the yellow jaundiced tinge to his skin and in his eyes went away.

The baby, who hadn’t even been able to roll over yet and who had very little appetite, was rolling from side to side in his cot and interested in food by the time he left Melbourne’s Royal Children’s Hospital.

It was a joy for Tanunda parents Louise and Cameron Schiller, who had watched their little boy struggle since being born with biliary atresia, a blockage in the ducts of the liver.

“In the first eight hours after surgery, Anthony had a bleed, so he had to go back into surgery to find the source. But after that, he came around in leaps and bounds,” Mrs Schiller said. “By the time he was discharged, you would never have known he was sick a day in his life.”

A week after his biliary atresia diagnosis, Anthony had his first surgery to try and save his liver. It was unsuccessful, so he was placed on the organ donor waitlist. Within three months, a match was found.

While he had missed a few early developmental milestones, the toddler soon made up for his slow start. He was walking by 19 months, his language development progressed rapidly and his poor muscle tone was soon a distant memory as he threw himself into swimming and Little Athletics.

In April, four-year-old Anthony was the youngest competitor at the World Transplant Games in Perth, competing in a sprint race, shot put-like “ball throw” and long jump, earning gold and silver medals.

“He met so many people from around the world,” Ms Schiller said. “International athletes were teaching him how to start at the starting blocks and he was having a ball interacting with them all.

“He’s a happy, normal little kid who has been given this amazing gift.”

Family celebrates Mia’s second and third chances at life

Mia Geise was “full of life straight away” after her second liver transplant.

It has been almost a year since the 11-year-old learned the liver she had received as a baby had “packed it in”. Fortunately, on the same day, her parents were told a new organ had been found for her.

“She was back at school six weeks later,” said her dad, Michael Geise. “Her teachers and everyone were so overwhelmed by how good she looked.

“She was back in the pool for swim training, doing squads. We have been careful managing the reintroduction of other activities, but she will also go back to dance this term, which is great.

“Before this transplant, Mia was feeling very unwell and struggling to do even routine stuff. In the 18 months leading up to it, she’d had to give up dance, drama and music.

“It’s fantastic to see how well she is doing now.”

Mia received her first transplant four months after she was born with liver failure. The Toowoomba girl suffered issues throughout the 10 years with that organ, but she has been luckier the second time around.

Mr Geise said he, Mia’s mum, Annie, and 13-year-old brother Henry were thankful every day for the two gifts that have allowed their little girl a second and third chance at life.

“As a family, we celebrate yearly on the date of her first liver transplant,” he said. “Without that first liver, Mia wouldn’t be here.

“We think of that donor and their family often. We also received a letter from the second donor’s mother, it was very heartfelt and I think it was important for her to know Mia was travelling well. We also share the grieving she has for the passing of her son.”

The Geise family urges others to register for organ and tissue donation.

“You’re never too young or too old to have organs that can help to improve the life of someone – or even save a life,” Mr Geise said.

Sydney dad feels a ‘real connection’ to heart donor

Jayden Cummins thought he had contracted the worst flu ever when he went to the chemist for over-the-counter medication in 2017.

One look at the Camperdown man and his pharmacist told him to go to his GP, who discovered he had a very fast irregular heart rate. She sent him straight to hospital where it was discovered he was suffering severe cardiomyopathy, or end-stage heart failure.

At St Vincent’s Hospital in Darlinghurst, Mr Cummins’ condition deteriorated and he was placed on a life-supporting extracorporeal membrane oxygenation machine.

The last words he remembers saying to his sister were, “please look after my boy”, referring to his then-13-year-old son, Henry.

Mr Cummins woke up from a coma three weeks later with a mechanical heart.

“For 436 days, I literally wore my heart on my sleeve,” the filmmaker joked about the artificial heart that temporarily replaced his damaged organ, and which was powered by a portable machine he carried outside his body.

“I was so glad to be alive. I wanted to do BridgeClimb but they wouldn’t let me, so I climbed Mt Kilimanjaro with my cousin and a mate. It took us nine hours and I cried all the way up there, I was so appreciative.”

Mr Cummins went on the organ donor waitlist in May 2018 and received his new heart nine months later.

He woke up the day after his surgery feeling “a million bucks” and with a new lease on life.

He has continued to embrace an active life, completing the City2Surf and the 28km 7 Bridges Walk, and winning the Anytime Fitness National Success of the Year award in 2018. He also got engaged to girlfriend Sanda Bowing after his transplant.

“I think about the person whose heart I have every single day, without fail,” he says. “I even talk to him.

“I feel like I’m the guardian of this heart, it’s not mine, it’s his, and I feel a real connection with him.”

From nightly dialysis to dancing, swimming and a normal life

Ruby England has been a “completely different child” since receiving a new kidney, her grandmother says.

Donna England will never forget the words the doctor uttered five years ago, when she took her then-four-year-old granddaughter to hospital on the advice of her doctor: “she has end-stage kidney failure”.

Ruby would sometimes complain she was tired and wake up with a swollen face, but her doctor would dismiss those symptoms as being caused by a virus when they quickly disappeared each time.

A strange bruise on Roby’s chest ultimately caused the doctor to send her straight to hospital, where blood tests revealed kidney failure.

“It was the worst night. To hear those words about a little girl who up until then had been like any normal child was rough,” said Ms England, who had been Ruby’s carer most of her life, alongside husband Craig. “I spent the night crying my eyes out.”

Ruby immediately had a tube inserted into her tummy so she could begin dialysis.

Every night for a year, she was hooked up to a dialysis machine from 7pm to 7am, even if it was her birthday or Christmas. This ruled out sleepovers or going on school camps. Even baths and showers were a tricky obstacle, as her tube had to stay dry and sterile.

Almost a year to the date that Ruby was put on the organ transplant waitlist, a perfect kidney match was found for her. She had the surgery in January 2021 and it wasn’t long before she was up and about.

Of the now nine-year-old, Ms England said: “She loves dancing and has singing lessons, she has such a very sweet voice. And she loves her swimming lessons and cooking.

“As a family (which includes Ruby’s brothers, Connor, 16 and Ashton, 13) we always remember that Ruby has this life because of the gift from the donor.”

Darwin woman’s post-pregnancy transplant a lifesaver

Three months after the birth of her second child, Efronsi Soula Yiannakos was diagnosed with a rare blood disorder that ultimately landed her on the organ transplant waitlist.

The 38-year-old Darwin resident was told she had atypical haemolytic uraemic syndrome (aHUS), a one-in-a-million nightmare triggered by her pregnancy.

Ms Yiannakos had already suffered from Type 1 diabetes since the age of five. Her aHUS, which causes blood clots to form in the kidneys, led to kidney failure and weeks of hospitalisation, dialysis and plasma exchange.

With a newborn daughter and four-year-old son at home, Ms Yiannakos spent seven weeks in hospital coming to terms with life on the transplant waitlist.

“It was devastating, I couldn’t be home to look after my daughter, or my son who was constantly asking ‘when’s mum coming home?’” Ms Yiannakos said.

For 22 months, she endured three-day-a-week dialysis sessions while navigating physical and emotional challenges.

After 11 months on the waitlist, Ms Yiannakos underwent a successful kidney and pancreas transplant in Sydney, freeing her from dialysis and insulin dependency while granting a second chance at a fulfilling life.

“My diabetes was well controlled with insulin and there was no evidence of the diabetes anywhere else in my body but the pancreas,” she said.

“The minute I had the transplants, my body took to them so well that I didn’t have to have the insulin, I didn’t have to do dialysis again.”

As Australia’s organ and tissue donation program maintains strict confidentiality, preventing health professionals from disclosing any information that could identify donors or recipients, Ms Yiannakos will never know who her donor was.

“I can’t thank them and their family enough,” she said.

“It’s hard to express because you don’t know these people, they’re complete strangers and they want to help others in a time where they’re grieving the most.

“I would still be on dialysis and I wouldn’t be well at all (without them). You don’t last forever on dialysis.”