When kids become violent: ‘It was like he was possessed’

ANGELA’S son is so violent and intimidating she used to hide from him in a wardrobe. She’s one of thousands of Australians who fear their children.

“I MISS him desperately,” says 54-year-old Angela* with eyes full of tears, “I do love him but I understand that the boy I knew up until he was 18 or 19 is no longer around. He’s gone.”

Angela isn’t talking about someone who is dead. She’s discussing her violent and ice-addicted 28-year-old son, Joshua.*

“I was giving him money all the time. And then when I would try not to give him money, that’s when the abuse would start,” Angela says, “he’s a lot bigger than I am and he’d sort of be standing over me and intimidating me.”

Eighteen months ago, Josh’s behaviour reached a new low.

“His bedroom door has got a glass pane and he’s punched that and sliced all his arm,” Angela recalls, “at that stage he was threatening me with a shard of glass.”

Angela was so frightened she got in the car and drove away. And as she did so, Josh was continually texting her photos of his cut and bleeding arm. He wanted to know: “Would I please come back and help him?” Angela explains.

No matter what was happening at home, Angela tried to always front up at work. Sometimes though, the pressure of “putting on a happy face” for her colleagues was overwhelming.

“It was hard every day getting up and going to work,” she says, especially because “people didn’t know what you were going through.”

Meanwhile, Josh was “unrelenting” — he would often phone his mother up to 25 times a day with different accusations and requests.

If going to work was hard, her home had become a prison.

“When he was intimidating me, the only place I felt really safe was in my wardrobe because I could sit at the back and have my legs pushed up against the door so he couldn’t get in,” she says.

On bad days, Angela would stay locked in the wardrobe until she heard Joshua retreat into his bedroom. It might be minutes. It might be hours.

“Once I’d heard him go his room, I knew that he wouldn’t come out,” she says.

Another altercation occurred when Angela tried to prevent Josh from driving her car while he was “off his face” on drugs.

“When I tried to stop him out the front of our house, he just flung me like I was a rag doll,” she says, adding: “It was like he was possessed.”

In an attempt to explain to me just how desperate she became, Angela says: “There was a really, really scary night that I was cooking dinner and chopping vegetables and I could have quite easily stabbed him. I had had enough. He was in my face standing over me and bullying me. I just wanted him gone.”

The years of escalating violence, stealing and manipulation by her son have certainly taken their toll.

“I was a good happy person but I just feel destroyed,” Angela says with emotion in her voice. “It was four or five years of just walking on egg shells.”

As the parent of a violent child, Angela is not alone. According to the ABS’s Personal Safety Survey from 2012, 63,100 Australian parents have experienced at least one incident of violence perpetrated by their child.

In Victoria alone, police recorded 11,770 individual parents who had been the victims of violence perpetrated by their children in the 2015-16 financial year. This accounts for just over 15 per cent of all family members affected by domestic violence in that state.

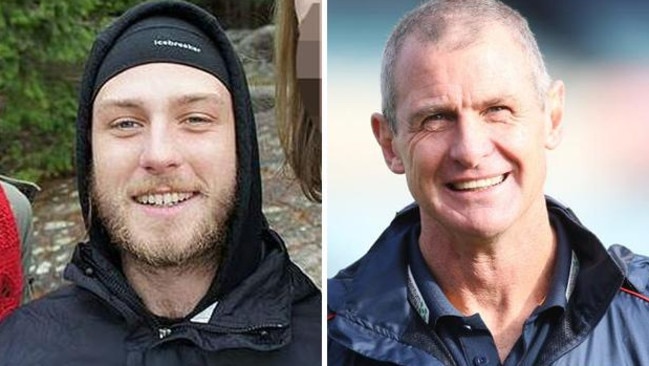

Eddie Gallagher is a Melbourne-based psychologist who has been working on the issue of child to parent violence for 25 years. In that time he’s worked with nearly 500 families experiencing this type of violence.

“In many cases these are well-educated, articulate, intelligent, modern parents and usually very caring,” he says.

“The parents are more child-focused than probably any parents were in the past. They’re spending a lot of their time doing stuff with their kids and for their kids, and their lives revolve around the kids.

“And that can make some kids very confident [and] secure but some kids have a sense of entitlement, where they treat their parents like servants,” he explains.

However, Mr Gallagher is careful not to blame parents for their children’s actions.

“This kind of parenting works really well with some kids and backfires with certain types of children and certain temperaments,” he says.

He adds that, “in about half of the cases I’ve seen, there’s a history of domestic violence.”

Although child to parent violence can start from the age of eight, Mr Gallagher says: “The key age for this kind of behaviour would be about 14 to 16 years old.”

In all the cases Mr Gallagher has seen, the children are verbally abusive to their parents. Many also make threats and destroy property.

“Some will, quite methodically, target belongings that their parents care about.

By way of an example, Mr Gallagher says, “Mum has got a collection of antique teapots, and they get a teapot and hold it up and dramatically smash it or tear up mum’s old photographs.”

“Kids are waving knives around, threatening not just the parent but even holding them to their own throat or threatening brothers and sisters,” he continues, “and that has become much more common in the last 10 years.”

Mr Gallagher says the verbal and physical abuse usually gets worse over time.

“So it often starts with verbal abuse and threats, and low-level violence like blocking and pushing. And it often escalates,” he says, “I’ve had parents with broken bones and brain damage.”

Pointing to a specific case where a teenage girl gave her mother brain damage, Mr Gallagher says: “The girls are just as physically violent as the boys. In fact, some of the most extreme violence I’ve seen has been girls.”

Even so, Mr Gallagher’s sample shows that roughly “twice as many boys as girls” perpetrate child to parent violence.

Mr Gallagher says victims are frequently single parents — both men and women — and parents in blended families. In two-parent families, all the mothers in his sample are abused but only half the dads.

Surprisingly, girls are slightly more likely to hit their father or stepfather than their mother — because they suspect their punches won’t be returned.

“I see it as a chivalry effect,” Mr Gallagher says.

Just as Mr Gallagher suggests, Josh’s behaviour got worse at he got older and only became unmanageable after adolescence.

Angela separated from Josh’s father when her son was three. But still, her son wanted for nothing. She moved in with her mother and sister and there was plenty of love and support to go around.

“I read to him every night and helped out at school canteen and was involved with all his sporting activities,” Angela says, “we were really close because we knew it was just us.”

Angela smiles with pride when she thinks of Josh’s childhood. She describes the lad she raised as “a really great kid” with a “great sense of humour” and “a super caring personality.”

While Josh wasn’t academically inclined, he loved sport. With deep sorrow, Angela says: “We always thought that he would make a great primary school teacher.”

The incident that finally broke Angela and Josh’s relationship occurred last year. Over a number of years, Angela had given Josh hundreds of thousands of dollars. Now she was using up the savings she’d accrued in a joint bank account with her long-term partner, Charles*.

“I just knew that I had to stop, I knew that it needed to stop,” Angela says. This time, she refused to hand over money. Josh became enraged and tried to leave the house with Angela’s mobile phone and tablet.

At Angela’s insistence, Charles had never previously intervened when Josh had an outburst. This time was different. A fight broke out and Josh slammed Charles into a chair and “cracked his ribs.”

Josh fled the house and Angela called the police. She took out an interim intervention order against her son.

“The hardest bit was that night when he came home breaching the intervention order, to actually then have to ring the cops and to have him carted off in handcuffs [and] loaded into the back of a divvy van,” she says.

Since then, Josh hasn’t been allowed back to their home. While Angela is making tentative steps towards contact with her son, it’s never easy. He’s still constantly requests money or other favours, such as being driven around.

However, these days Angela feels far more able to set boundaries. Through a relative, Angela got in touch with a local branch of Tough Love, a national support group run by parents “experiencing difficulties with their children.”

For Angela, it was a revelation. She wasn’t alone. And not only that, these were caring, loving parents just like her.

“[To] be able to share with other parents and have other parents ring you during the week to find out how you are, that was great,” she says.

Mr Gallagher agrees that meeting other parents in the same situation can be the best salve. Twelve years ago he developed a program for parents with children who exhibit challenging behaviours titled, “Who’s in Charge?”

The program — which is currently running in six states and territories across Australia and also a number of locations in the United Kingdom — gives parents a chance to meet each other. It also helps them to work through any guilt they might feel and set logical consequences for their children.

In contrast to other forms of domestic violence, Mr Gallagher believes it’s vital to address the perpetrator’s behaviour with the victim.

“Most of these children are reluctant clients,” he says, “they may not be motivated ... to come for counselling.”

On the other hand, “if the parents change their parenting style, that is far more long-lasting and can have a much bigger impact — especially if the child is in early adolescence or younger,” Mr Gallagher says.

Angela believes shame and stigma both play a key role in this type of family violence.

“As a parent I would ask myself: ‘Is this my fault? What did I do? What didn’t I do?’

“I was embarrassed and humiliated to say [to others]: ‘I’ve got a violent, ice-addicted son at home,” she says.

For Sharon*, a 46-year-old mother of five, her family’s cycle of domestic violence has been nearly impossible to break. It started three generations ago.

“My dad used to hit my mum and then when my mum left him a long time down the line, she met somebody else and he was worse than my dad. He actually put my mum’s head through a wall,” she says matter-of-factly.

It took a long time — nearly a decade after they married — before Sharon’s own husband, Michael*, became violent.

“It got worse after the kids were born,” she says, “I used to always stick up for the kids and that’s when I used to get it.”

“They saw their dad yelling at me all the time, most of the time.

“He had a lot of [chronic] pain and so he used to drink a lot ... and that’s when he used to get violent,” she says.

The violence wasn’t just directed at Sharon, but the children too.

“If they’d did something wrong he would slap them across the head, hard,” she explains.

Sharon’s oldest son, 19-year-old Martin*, was always a challenging child to parent. He suffered developmental delays and was diagnosed with ADHD as a teenager.

By the age of 10, Martin had started having angry outbursts and hitting his mother and sisters.

“You just used to say something small to him and he’d go off his head,” Sharon explains.

Two years ago Sharon and Michael separated — and that’s when Martin’s behaviour really escalated. He’d punch holes in the walls and throw things.

“He used to punch me in the stomach [and] he’s pushed me over once or twice,” Sharon recalls.

Reflecting on her son’s violence, Sharon confesses to feeling “guilty because of the way his dad ... used to hurt him. I couldn’t protect him.”

When a row erupted over Martin’s broken phone in April last year, Sharon was afraid he’d suffocate his younger sister, Carly.*

“He went really angry and started hitting her and pushing her head on the floor and on the couch and punching her.

“He really pushed her head into the blankets and I thought he was going to hurt her bad,” Sharon says.

This anecdote is so shocking, I’m forced to ask Sharon: Were you scared Martin would kill Carly?

“Yes,” Sharon replies without hesitation.

When child protection services discovered the extent of Martin’s violence, Sharon’s four daughters were taken into foster care. In order to get her daughters back and restore some peace in the household, Sharon took out an apprehended violence order against her son. Martin was forced to leave the family home.

“I found there were knives in his bedroom and I found out he was on ice and then I said, ‘That’s it, he has to go,’ she says.

That was more than a year ago and Sharon describes herself as “definitely hopeful” about the future. She’s being seeing a psychologist regularly and is taking part in an intensive family coaching and support program.

Sharon believes Martin’s his life is also getting back on track. He’s currently receiving ongoing support from an organisation that assists people with cognitive disabilities.

“There is hope out there if you ask for help and accept the help,” she says.

WHERE TO GET HELP

In an emergency, call 000

If you need support or counselling for domestic or family violence issues, call 1800 737 732 (1800 RESPECT). It’s a 24/7 national service, so it doesn’t matter where you live.

Tough Love: www.toughlove.org.au

Read this excellent booklet, put out by Relationships Australia (SA)

Eddie Gallagher’s website: www.eddiegallagher.com.au

* Names and some identifying details have been changed to protect the safety and privacy of those in this story.

Ginger Gorman is an award winning print and radio journalist, and a 2016 TEDx Canberra speaker. Follow her on Twitter @GingerGorman