The age when my life changed

ONE year Gary was a happy kid, doing cartwheels in the playground. A year later, his whole life had changed.

THIS story has a happy ending. But its beginning saddens me even now.

I choose not to tell the beginning if I can help it. I go straight to the positives, the progress, all I’m grateful for in my otherwise charmed life.

But today I’ll tell it because we’re approaching National Coming Out Day (11 October) and my story, like so many others before me, shows how much better things can get.

It’s an important message for anyone who can’t see that right now. Especially young LGBTQI people whose self-worth may have nosedived in the last 12 months, following the divisive marriage equality postal vote.

When I was eight, my show-and-tell was that I could do fifty cartwheels in a row. As classmates counted them, I felt free and proud of myself. It’d be the last time I’d feel that free for a decade.

Related: Uniting Church of Australia consents to same-sex marriages at its premise

Related: Royal family’s first ever gay wedding

By nine, I started to understand I was different from non-cartwheeling boys. By ten I learnt I needed to hide it, to assimilate. By eleven, my difference felt increasingly wrong.

Twelve was the first time I heard the word ‘queer,’ usually prefixed by ‘dirty.’ By thirteen I knew I needed a new persona and by fourteen the pretence was fully formed. I no longer knew who Gary was; only the version of him that felt acceptable to the world.

At fifteen I was utterly convinced what was festering inside me was a disease, was my fault, and I’d die a million social suicides if a single soul discovered. The word ‘gay’ was so repulsive to me, I heaved at it. Coming out didn’t just feel terrifying. It felt impossible.

Then, at 17, my dirty secret was discovered. That year is too painful and personal for me to put into words, but my world imploded. I was revealed as a phony, an impostor and a deviant. It was humiliating. I was ashamed.

But rock bottom is when things start to get better. The worst had happened and I was still breathing.

Aged 18, I made the best decision of my life. I vowed I’d never be in the closet again.

Looking back now, I was extremely lucky.

I’d secured a university place in a bigger city, miles from my hometown. An opportunity presented itself for me to re-create myself from scratch, away from everyone who’d known the old, closeted me.

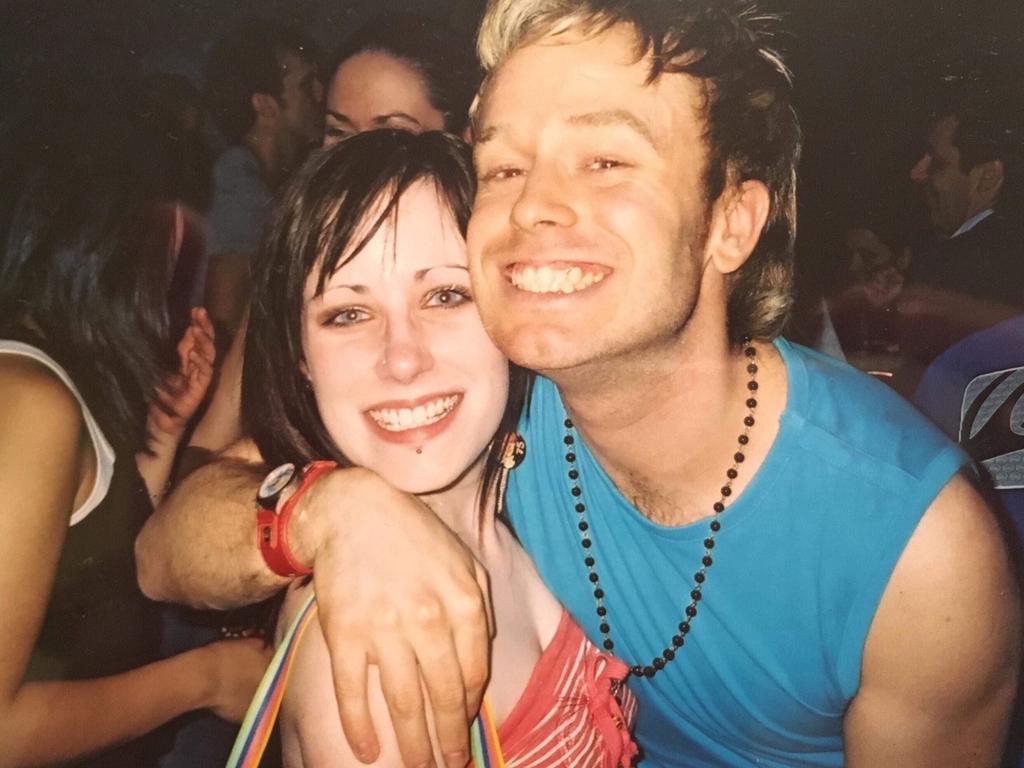

Really, I was doing the opposite of re-creation. I was, for the first time in ten years, giving myself permission to be myself — in a safer environment. I cartwheeled into those halls of residence with all the freedom and pride of that eight-year-old. I discovered who Gary really was. I decided I liked him. I still do.

The hardest thing about coming out was that the homophobic bullying wasn’t just in the playground. It was in newspapers. It was spouted by conservative MPs. It was in everyday conversations between adults who should know better.

I was born into a hostile world.

The lack of role models meant I felt so completely alone; there was no internet, no sense of the colourful, diverse LGBTQI community that would welcome me later in life. It didn’t occur to me you could be out, gay and happy. I couldn’t see it so I couldn’t be it.

My gay forefathers were largely a lost generation: either lost to suicide, lost to drink and drugs to cope with society’s ostracism, lost to the HIV crisis, battered by homophobic violence or closeted. It was fight or flight and they either fought to the death, or they fled this hostile world. I’m grateful to every single one of them for blazing a trail that now shines brighter than they could’ve imagined. I just wish more of them were here to see it. The fruits of their labour; their suffering.

The remaining few weren’t visible until I was brave enough to buy my first Gay Times magazine aged 17, my trembling hands fiddling for the change and my rosy cheeks betraying me. But the shaking and blushing was worth it, for here it was, what I’d craved for so long: solidarity.

The hangover effect persists. Statistics from Australia’s National LGBTI Health Alliance show that LGBTI young people aged 16 to 27 are five times more likely to attempt suicide than the general population. These are people like Brisbane’s Tyrone Unsworth, who took his own life in 2016 following horrendous homophobic bullying. He was 13.

LGBTI people are twice as likely to self-harm and nearly six times more likely to be diagnosed with depression. With the Safe Schools program now de-funded by many states, Australia is without a national program to tackle the epidemic of homophobic bullying that leads to these depressing stats.

But I told you this story has a happy ending. This year, as a journalist, I’ve told the stories of young people who’ve come out at ages that, to me, were stupefying.

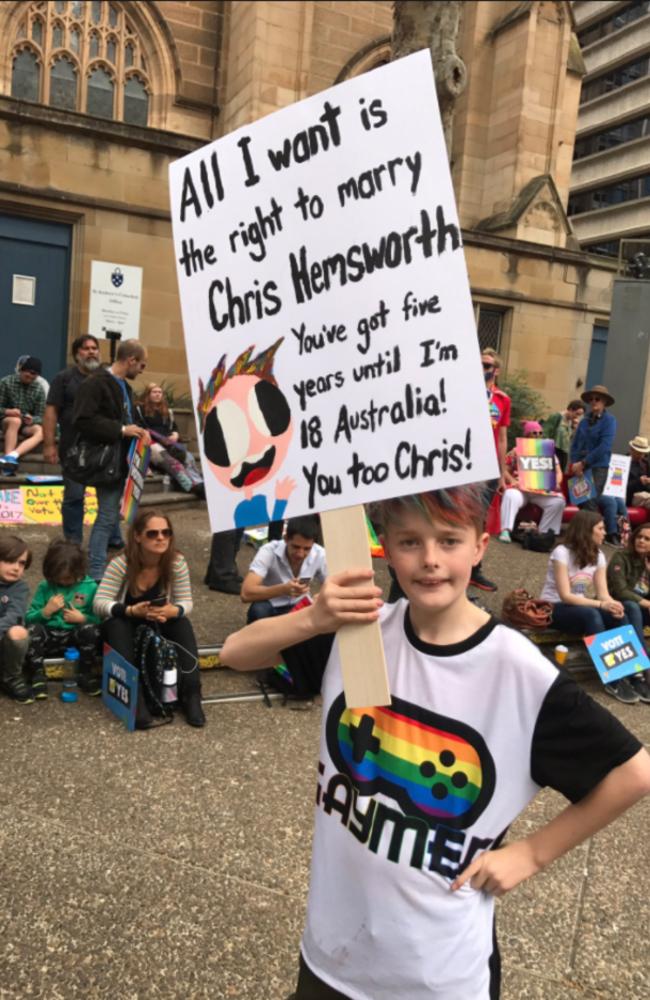

Reporting on Sydney’s huge marriage equality rally, I met Max Townes, 13, whose banner about wanting to marry Chris Hemsworth went viral.

He came out aged twelve. Twelve! His best mate said it felt like his birthday gift. At my school, my gift would’ve been pariah treatment.

I told Kate Rowe, one of the 78ers, about Max. She said “If I could meet him, I’d absolutely hug him. To be at ease with himself, and have the space to explore his sexuality so young, he’s going to be one very strong man.”

“Now that,” she said triumphantly, “is what you call progress.”

That hostile world, in my mind, was thawing.

It was positively warm when I interviewed Australia’s youngest professional drag queen, Cullan Jeffs, 15 (aka Verity Von Queef). His first drag performance was when he was 14. Fourteen! His mum is so supportive that she orchestrated for him to have his very own drag mother, Sydney’s Penny Tration. And he’s never been in, so he’s never needed to come out.

The story last year that Roman Blank came out aged 95 reminded me how lucky I’ve been to be born into a generation when coming out was even possible. Roman was married to his wife for 65 years; when deciding whether to commit suicide or remain closeted, Roman said “I chose to live.”

From 12 to 95 years old, the last 12 months have seen my gay brothers all over the world shunning society’s rigid expectations of masculinity, and choosing to live their own way.

It’s enough to make you want to do fifty cartwheels in a row.

- Gary Nunn is a freelance journalist. Follow him on Twitter @garynunn1