Miracle that saved girl from Auschwitz gas chamber

A SURVIVOR has told of the unlikely chain of events that saw her beat “pure evil”. WARNING: Graphic

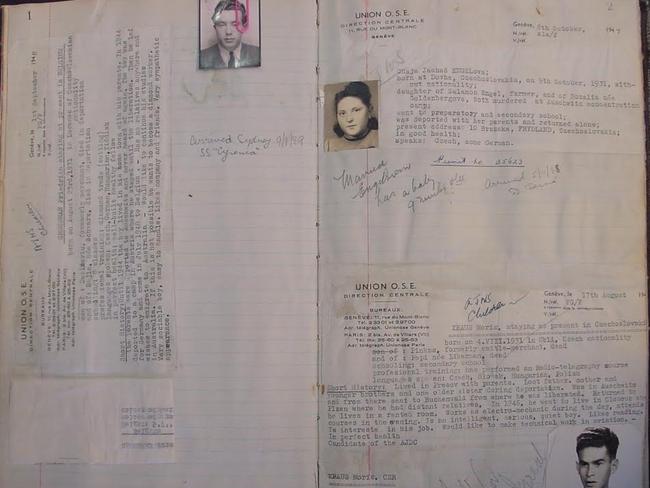

YVONNE Engelmann was just 15 when she was rounded up with her family and sent to Auschwitz concentration camp, one of the network of German Nazi extermination camps operated by the Third Reich in occupied Poland in World War II from 1940-1945.

But it was an unlikely miracle that saw her survive to tell the disturbing tale.

After arriving at the camp, Yvonne was immediately sent to the gas chamber. Thanks to some strange twist of fate, it malfunctioned and she was left naked in the chamber overnight before being freed.

By some miracle, the Nazi’s kept her alive, and she was sent to sort through the clothes of newly arrived Jews to find any gold or valuables they’d hidden.

Her “job” saw her stationed in between the crematorium (which burnt 24-hours daily) and the gas chambers. She ended up being the sole survivor from her entire family, and made a new life for herself in Australia.

This is Yvonne’s story.

**********

“I was 14 and a half when war broke out,” Yvonne tells news.com.au.

“I wasn’t allowed to go to school, I couldn’t walk on the street, I had to wear the yellow Star of David and couldn’t mix with any non-Jewish people. Friends I’d grown up with now totally ignored me, solely because I was born a Jew.

“My father was taken to the police station many times and we never knew if he would come back. One day he returned and his front teeth had been knocked out. We lived in fear constantly — we had no idea what would happen to us in the next hour, let alone in the next day.”

Born in Czechoslovakia to shopkeeper parents, Yvonne was an only child.

“I had the most wonderful childhood that anyone could wish for, but unfortunately it was short-lived.”

In the limbo of uncertainty, things went from bad to worse. Her parent’s shop was taken away and the family was forcibly removed from their home to a cramped Jewish ghetto.

At the approach of her 15th birthday, she and her family were taken from the ghetto — along with hundreds of others — to the railway station where they were piled into dozens of cattle wagons.

“Men, women, children, screaming babies — the journey was too horrific to even describe,” she recalls.

“There was no ventilation, it was hot, an overflowing tin bucket was the only toilet … we were stripped of our humanity.”

After five long, gruelling days, Yvonne and the rest of the human cargo had arrived at their final destination: Auschwitz. The most notorious Nazi death camp in history.

Forced out of the dark, stinking container into the bitter cold, Yvonne faced rows of menacing German officers and barking dogs. After being assembled into lines, a Nazi officer stepped forward and the “selection” began.

“Doctor Mengele,” she says, shuddering.

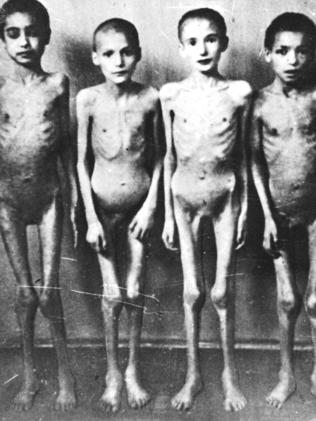

Responsible for sending countless numbers of innocent people to their immediate deaths with a casual flick of his wrists, history would later dub this evil doctor as “the angel of death” due to his twisted “scientific experiments”. Women were sterilised, men had their genitalia removed, children were infected with chemicals, dissected and even frozen to death.

“Death to the left, life to the right,” she recalls.

“If you didn’t look healthy or well-developed, you were shown with the finger to the left and if you were developed and fit-looking, you were shown to the right with the finger.”

Huddled in between her parents, Yvonne was ushered right and her parents to the left.

“Our eyes locked briefly and then they disappeared into the mass of terrified people. That was the last time I ever saw them,” she says, sadly.

Yvonne’s hair was shaved and she was forced to strip naked.

Yet Despite Mengele’s decision, Yvonne was ushered into what appeared to be a gas chamber, a simple room filled with what appeared to be shower heads.

“We were forced to strip, our hair was shaven and then — to this day I’m still not really sure what was happened.

“I had no idea what it was — I was in such a state of shock, I didn’t think anything. I was shaking with fear so much so that I was too afraid to even cry.”

Locked in the room in darkness with naked strangers all around her, they waited. Afraid.

Nothing happened.

“The gas chamber must have malfunctioned,” she reasons.

“In the morning we were marched out and then put to work.”

The fact she was shaved before means she was in a shower room as part of prisoners' registration process, not in a gas chamber. @newscomauHQ https://t.co/4tHKmDQ5rf

— Auschwitz Memorial (@AuschwitzMuseum) October 2, 2016

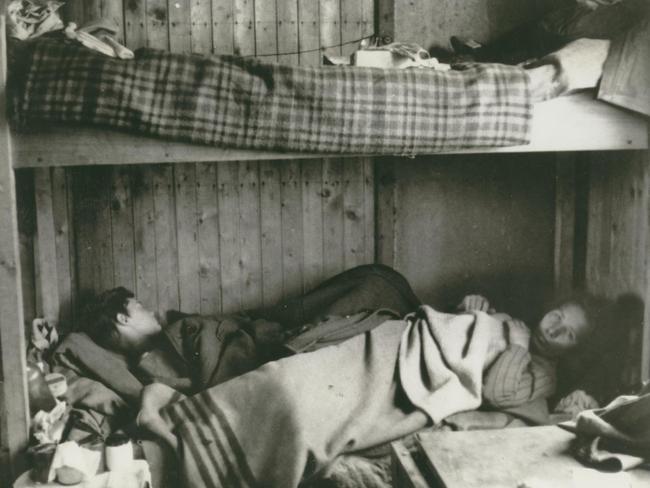

Life in the camp was a cycle of misery. Beaten regularly and surrounded by the prospect of death meant that surviving for one more day became her only goal.

“We were so hungry,” says the 88-year-old.

“When I see people throw out things today I feel so sad. I can’t even throw out a piece of bread. Until you suffered hunger like I did — real hunger — you can’t know what it’s like.”

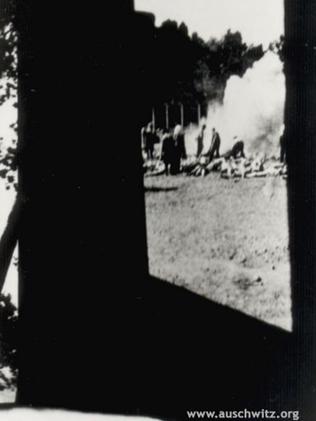

Yvonne’s job meant she had a ringside seat to the horrors of Auschwitz. Tasked with sorting through the garments of thousands of new prisoners in search of hidden valuables, she was positioned between the gas chambers and the crematorium, which was in operation 24/7, burning the bodies of some 6,000 people killed daily.

“The smell of human flesh being burnt filled my nostrils. When I think back to it now, I have no idea how I found the courage to go on,” she says.

It was at this point that Yvonne recalled the promise she had made to her father on their last night together in the cattle wagon.

“He made me promise to him that I would survive,” she remembers.

“I didn’t understand what he meant. I thought, ‘Of course I’ll survive.’ Keeping my promise helped me get through it all. Also, I never lost faith. When you’re in real, terrible trouble like I was then, if you have something to hold on to, it really gives you strength and courage.”

After close to six months in the camp, Yvonne and the other inmates were forced to leave as part of what is now known as the “death marches”. Faced with imminent defeat, Nazis devised a plan to kill as many of the remaining Jews as possible by marching the already ill and malnourished prisoners for weeks during the bitter winter. Anyone that was too weak to keep up was shot.

“Walking for weeks through freezing temperatures, through snow and hail I was hungry. I had no hair, no warm clothing and my body was riddled with lice. I ended up with bad frostbite on my face.

“I still have the marks,” she says, raising her hands to touch pronounced red patches on her cheeks.

Forced to walk to Germany, the Nazis put her to work for months in a munitions factory until being liberated by the Russian army.

It was May 1945 and the war was over, but for Yvonne her journey to recovery was only just beginning.

“I was the sole survivor of my family. Can you imagine how that feels?” she asks.

“Nobody to give you a cuddle, no one to say something to cheer you up, nobody to give you advice. At the age of 16, I was totally and completely on my own.”

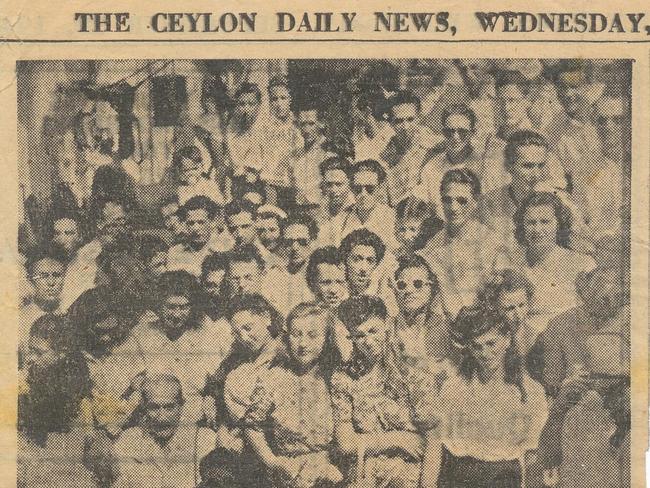

After spending months in hospital recovering, Yvonne had to look to the future. So, at the age of 17, she made the decision to emigrate to Australia and begin life anew.

“I had to be very strong,” she says, matter-of-factly.

“I didn’t know anything about the country, all I knew that it was far away — very far away and that suited me. I had nothing left in Europe.”

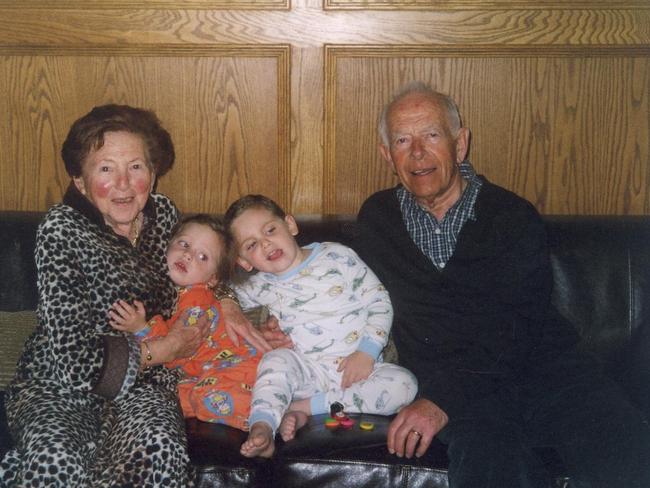

Taken in by a Jewish family, she gradually learnt to speak English and then married a fellow concentration camp survivor one year later, beginning the process of creating a family.

“First my three children, then nine grandchildren and then 11 great-grandchildren,” she says.

But the experiences in Auschwitz still haunt her — even at the age of 88.

“I have been in Australia for 68 years now, but it has never left me,” she says.

“Because of that horror, because of that constant fear, I’ve suffered from anxiety ever since.

“I never had any counselling — not even five minutes. We had to work everything out on our own and just make the most of it.

“Nowadays, it’s offered after any kind of trauma, but after our experiences we were just expected to get back on with our lives.”

Conscious that she’s one of only a handful of survivors left, she’s determined to make sure those who were murdered at the hands of the Nazis — including her own family — didn’t die in vain.

“I have a duty to tell my story,” she explains, her eyes filling with tears.

“At least 1.1 million prisoners died at Auschwitz — around 90 per cent of them Jewish — making up part of the six million-plus Jews killed during the holocaust. We need to teach people about what hatred can do.

“That was the first time and — thankfully — also the last time I have experienced pure evil.”

Yvonne survived the gas chambers and the brutal regimen of Auschwitz. And while she may have lost her family in the process, she has never lost hope.

— Yvonne Engelmann is a regular speaker at Sydney’s Jewish Museum. Find out more information at www.sydneyjewishmuseum.com.au.

— Paul Ewart has lived and worked in three different continents: from the heady metropolis of Dubai, to North America and — as of seven years ago — Sydney, Australia; a place he now calls home. You can find out more about Paul at www.paulewart.com.