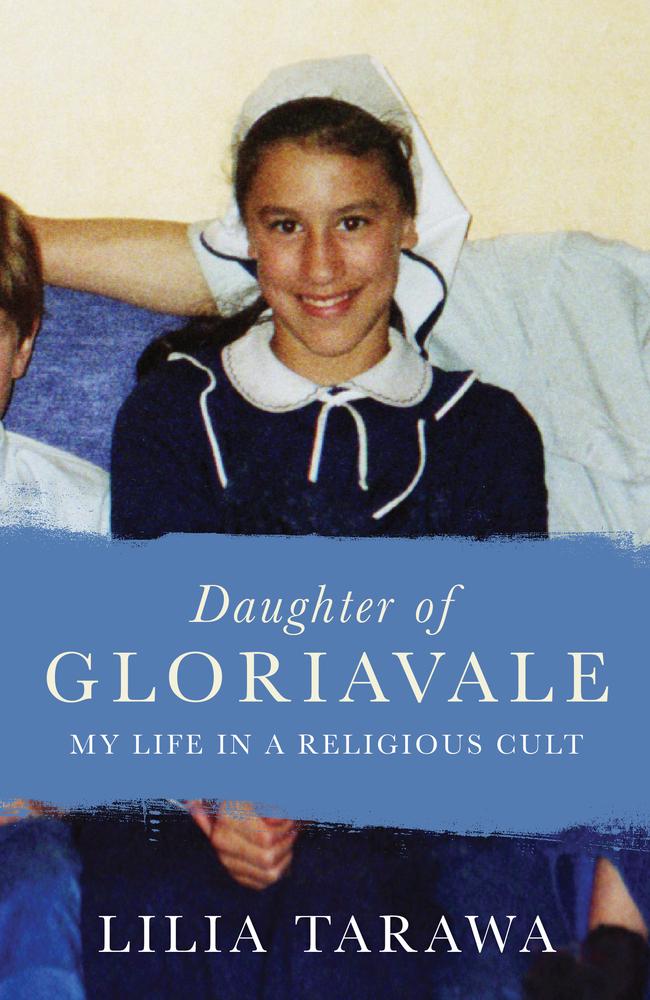

Life after Gloriavale, the repressive cult run by an Australian sex offender

LILIA Tarawa grew up in a fundamentalist cult where women had to submit to men. But she eventually broke free.

LILIA Tarawa is 26 years old, but she’s really only eight, she says. That’s how long she and her parents have lived in the real world.

The New Zealander grew up in the repressive, fundamentalist cult of Gloriavale Christian Community, founded in 1969 by her grandfather Neville Cooper, aka Hopeful Christian.

Australian-born Cooper — whose followers are also known as Cooperites — is a sex offender who was jailed on three counts of indecent assault against girls aged 12 to 19, and married a 17-year-old at the age of 69.

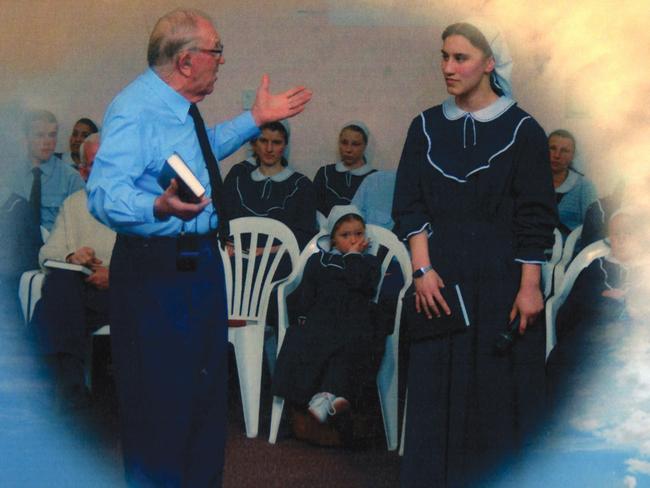

Around 90 families live at the commune on the west coast of New Zealand’s south island, following its strict, oppressive rules. Women are considered subordinate to men and live a life of domestic servitude, forced to submit to male community members at all times and wear headscarves, along with loose, full-length blue dresses with high necklines and long sleeves. They share everything — from meals to prayers to childcare — with mothers breastfeeding each other’s children. Young girls are married off as teenagers. Access to the media is tightly restricted. At times, the families take part in strict fasts, eating nothing for days or living on rice for a month.

The fear of eternal damnation hangs over their heads at all times.

‘HER CHILD HAD BLUE WELTS ACROSS HIS BACK’

Children are at the bottom of the Gloriavale hierarchy, and Lilia says old-fashioned corporal punishment was encouraged at the community-run school. “I remember seeing a boy belted with a rod in front of all of us,” she told news.com.au. “A schoolteacher beating and kicking a boy when I was 11.

“One of the wives once showed me her child with blue welts across his back. I started to think, ‘This isn’t right.’”

But Lilia pushed these thoughts away. “Even if you think it’s wrong, you’re not allowed to speak,” she says. “You learn to suppress those emotions. You just do it, everyone does, you are under the control of the leaders. We’ve been in a mindset since we were really young of, ‘I have to obey’. If you don’t, you feel really guilty. At the time, you think it’s your own will.”

When Lilia received a school report that praised her “leadership qualities”, her grandfather read it aloud at dinner and mocked her in front of everyone, announcing that they didn’t want “bossy” women like her at Gloriavale. She was “humiliated”.

Lilia knew as a child that her grandfather had been to prison but had been told he was “a martyr to the faith”, and was so young she “didn’t think anything of it”. When she discovered the truth about his crimes, she was extremely distressed. Today, she sees him as a “controlling and manipulative” person, but is oddly philosophical about this charismatic leader’s disturbing history. She says she never witnessed any sexual abuse in the community. “He’s my grandad, I will always have love in my heart,” she explains. “Not everything he’s done has been a mistake.”

‘TO EVEN MENTION THEM WAS A SIN’

At 16, Lilia made a vow to her grandfather during her commitment ceremony, promising she would submit to men, look after the home and remain “meek”, “modest” and “pure”. She renounced adultery, divorce, birth control and abortion.

It was Lilia’s two older siblings who began a rebellion. “It was simple things, listening to wordly music, wearing sunglasses, which we weren’t allowed to do, rolling their sleeves up. These were all signs of rebellion. They ended up running away. My brother was gone. My sister was gone.

“When people leave, they’re shunned, or excommunicated. For us to speak to them or even mention them was a sin. I watched it break my mother’s heart. I was 15.”

Lilia’s parents were deeply indoctrinated. They were leaders themselves — her mother Miracle, who grew up under the same rules, was House Mother to the women, while her father Perry travelled overseas managing a moss export business, one of several run by the cumminty alongside dairy and sheep farming.

But the couple’s love for their children made them do something unprecedented in the community: they moved to a separate house with all the kids close to Gloriavale, remaining part of the cult.

“I started to have more exposure to outside influences,” says Lilia. “Small things like pierced ears, shorts instead of trousers, T-shirts with graphic prints, hip-hop, Eminem.

“Those things drew me in. I was so torn and confused. I was living two lives.”

Eventually, the family that “had been broken apart by the rules of Gloriavale” decided to leave for good.

Cutting ties with friends and relatives was painful, however, and Lilia is still working on overcoming her old convictions and “rewiring her whole brain” today, working as a health and lifestyle mentor in Christchurch and publishing a book called Daughter of Gloriavale: My Life in a Religious Cult.

‘YOUR WHOLE LIFE IS LIVED IN FEAR OF HELL’

“You believe you are going to go to hell, burn in hell,” she says. “Your whole life has been lived in fear of hell. It’s an intense way to live ... It’s the religious control that takes over your life.

“It’s taken a long time to figure out who I am. You go from having no choices to having all choices, your career path, how you dress yourself, who you marry.

“Do I agree with the philosophy of Gloriavale? No, that’s why I left. But there are things we could learn that could be helpful to society. It taught me a lot about life ... awesome social skills, how to work in a team, practical skills, how to cook, sew, spin, care for a child ... I guess just skills on the domestic side.”

These days, Lilia wears fashionable clothes and lipstick. She’s given up religion, dated men and completed a university course. Unlike others who have left Gloriavale, she never went completely off the rails.

“It’s been baby steps, from subservient Christian teen to outspoken, gregarious woman of 26,” she says. Since writing her book, she has receives messages from people all over the world telling her how helpful her words have been.

“I’m writing the book speaking about discrimation and abuse for people who can’t,” she says. “Just maybe, my book will give people the courage to step out of it. These are disempowered people with other people in control, narcissists who are taking advantage of them.”

‘YOU LIVE IN THE SHELL OF THE PERSON YOU ARE’

Lilia says she is “pretty happy” with the person she is today. “No regrets,” she says. “None of us gets to choose our parents, the life we’re given, it’s more about how we can live.

“I meet people every day, their stories are powerful and amazing. They’re overcoming limits and breaking boundaries. I don’t feel special.

“Suppression doesn’t just happen in cults, it happens every day in the world, relationships, government. I’m giving those people a voice. I’m passionate about racism, sexism, child abuse. I’ve seen it first hand, how it can kill people’s mental health and rob them of joy.

“Living in suppression isn’t a nice way to live. You really lock away parts of yourself. You don’t know everything’s better outside because you don’t know what freedom feels like. African people in slavery had to fight for freedom and that’s how I feel about my time at Gloriavale.

“You take your creativity, voice, ideas, intuition and lock it in a box, bury it, pretend it’s not there and live in the shell of the person you were created to be.”

Lilia compares leaving the cult to a birth, like a snake shedding its skin or a butterfly emerging from a chrysalis. “New life is painful. When you find your voice, it’s one of the most painful things, but you feel everything so much deeper, the sky is so blue.

“To leave Gloriavale meant to sacrifice many people I loved, friends, family, people I went to school with and worshipped with. Leaving those people was the hardest thing I’ve ever done. I had to do through it for freedom, and when I came out, I still didn’t know who I was. I had to go through a grieving process for all the things I believed.

“I’ve been able to get a sense of who I am. That’s really empowering and what I’d call freedom.”

You can buy Lilia Tarawa’s bookDaughter of Gloriavale: My Life in a Religious Cult for $32.99 at Booktopia.

Leave a comment below or share your story — email emma.reynolds@news.com.au or tweet @emmareyn.