I wasn’t allowed to divorce my abusive husband

ANNE Aly was married only weeks after meeting her husband. When he started hitting her she went to a judge who refused to grant her a divorce.

ANNE Aly moved to Australia when she was just two years old, but was still very connected to her birth country of Egypt.

It’s where she met her husband, who she had known for just weeks before marrying. While neither were particularly religious, when their marriage was in trouble, he started threatening her with sharia law. Following is an extract from Ms Aly’s memoir Finding My Place.

SHERIF’S visa arrived just ten days before my due date and he flew over immediately.

I gave up working and we moved into the little home I had made for us with its second-hand furniture and handpainted baby bassinet.

As my due date approached, complications with the pregnancy started to arise. I was big. So big that I was sure I was going to be pregnant for the next three years and give birth to a baby elephant.

So big that excited strangers stopped to ask me if I was pregnant with twins — like they’d suddenly discovered a secret I had been hiding under my ugly maternity clothes. What do you say to that? All I could muster was a polite smile and, “No. It’s water. I have a lot of water.”

What I really wanted to say was, “Seriously? I’m already panicking about having to pass a watermelon through my vagina and you really want me to get excited about the prospect of having to pass two?”

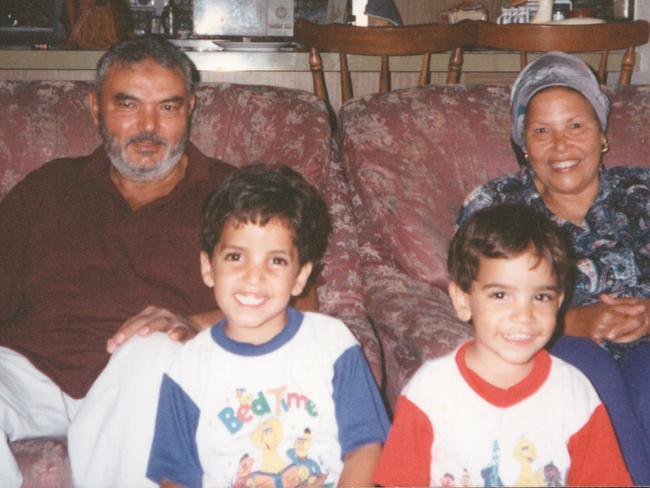

When my due date passed without a baby to show, my doctor admitted me to hospital. Three days later Adam, my firstborn son, mewed and puked his way into this world through an emergency caesarean section.

I didn’t get to hold him until he had been cleared and I had stopped shaking from the epidural. I don’t think I had ever laid my eyes on anything so beautiful or felt so much love for anything in my entire life until that day. It is so indescribable that I could never possibly have all the words to express what it feels like to hold your child in your arms for the first time.

And by the way, all that breathing and focusing and everything I had learned about how to have a baby went out the window with the proverbial bath water as soon as I felt that first excruciating pang of labour.

We took our little boy with his shock of dark hair and his little chin dimple home and I settled into my new role as Adam’s mum. We soon bought our first home — a three-bedroom, one bathroom house just three doors down from my parents’ home in Perth’s southern suburbs. Adam would have been around eighteen months old the first time his father hit me so hard it left me bruised and scarred.

The argument started — as all our arguments did since we had been married — with me demanding an answer to where he had been for the last twenty-four hours or so, and him answering me as he always did: “You can bang your head against that wall until you bleed to death, you will never know where I have been or what I have been doing.”

It was his standard answer for everything and the way he maintained his control by being the keeper of the information I so wanted to know. Where had he been? Why hadn’t the bills been paid? Who was the strange man that kept calling? Why did his stories never add up?

Why had his friends told me something completely different about where he grew up and what university he went to? Where was his American citizenship and why didn’t he use it to make it easier for him to come to Australia? Every question met with the same answer — “Bang your head against the wall.”

After days of pleading with my parents, my mother finally agreed to accompany me to the Fremantle courts to get a violence restraining order against Sherif. Divorce wasn’t something that my parents encouraged.

They were concerned about how I would survive without the shade of a man to insulate Adam and me against the harsh realities of single parenthood. Nobody in my family had ever been divorced. This wasn’t something that “we” did. “We” sacrificed; “we” were patient; “we” wore our unhappy relationship like a badge of honour that read: “This is what a good wife looks like.”

I stood in front of the judge, an older, grey-haired male, and relived every painful blow and every humiliating slap. The judge looked at me like he was examining a dirty nappy. “Have you thought about this?” he asked. “Do you really want this? Do you have any idea what it means? It means that the police will come to your house and take your husband away in front of your son. Is that what you want?”

He looked towards my mother, who sat silently behind me showing her support in the only way she knew how. “After all,” he began, “surely your culture and traditions would have their own way of dealing with this.”

As a twenty-something mother with a toddler to care for, the judge’s words eroded my resolve, and I didn’t pursue it. He might as well have banged my head against the wall until I bled to death.

I walked out of the courtroom that day knowing that if the judge in all his wisdom would not help me, then my mother, who still believed that women were too weak to withstand life outside the shadows, would withdraw what little support she believed she could give. So I stayed. I stayed because like so many other women, I had nowhere else to go.

********

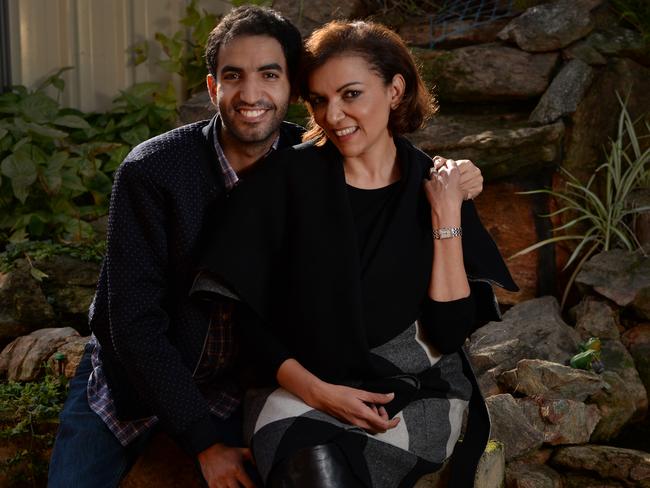

Less than a year later, I was blessed with another baby — a son. We named him Karim, and if I thought I couldn’t possibly have enough space in my heart to love another child as I did Adam, I was wrong.

I tried to follow my mother’s advice of being patient in the hope that my husband would turn into a good, loving man who wouldn’t hit me and who stayed home and looked after me. I tried that because as they say, the first five years are the hardest and all you need is just a little patience.

That’s not true. Patience actually got me f**k all. I went to work so that I could pay the bills that weren’t getting paid. I took my babies to play group and child care and to the park and movies and toilet trained them and loved them all by myself. I accepted that their father did not want to change their nappies or bathe them or hold their hands and I did it all.

And despite this — despite the loneliness and the beatings and all the s**t — leaving my husband, the father of my sons, was the hardest thing I ever had to do. I held my three-year-old and my one-year-old baby close to my heart and cried — my tears falling on to their sleeping heads and making their hair so wet it stuck to their little foreheads.

“I’m so sorry,” I sobbed. “I’m so sorry that I can’t do this anymore. I’m so sorry that I’m going to put you through this. Please forgive me. I love you.”

********

When Sherif finally did leave the family home, he did not do it compliantly. He wasn’t about to make things easy for me all of a sudden, and he left me with a mortgage and some pretty hefty debts.

In desperation, I went to the Department of Social Security for help. The glass doors of the department opened to a cavernous room where industrial-grade carpet and linoleum endured a million footsteps heavy with the weight of poverty and destitution.

I carried Karim on my hip and held Adam’s hand as I waited for my number to be called. The man behind the desk looked much like any of the other twenty or so white collars behind counters where all the other people who had nowhere else to go lined up waiting to be served. I sat on the chair opposite him with Karim on my lap and Adam by my side.

“It usually takes about five weeks to process a payment,” he told me.

“Five weeks? What am I supposed to do in the meantime?” I asked, horrified.

“Well, that’s how long it takes. Could be longer. Is there anyone who can help you out? Do you have any family who can lend you some money to tide you over?”

I bowed my head and shook it slowly. “No. Nobody,” I whispered, holding back the tears.

********

Within nine months of the end of my marriage, I had submitted my thesis in completion of my Master of Education. I immediately went to work teaching English at a language school in the city. It was casual work with no long-term security, but it was enough for our little family.

By then, Sherif had all but vanished from his sons’ lives. Occasionally, he would make the time to call from his new home somewhere in Sydney, where he had moved for work.

In principle, I believe that children have the right to form relationships with both their parents, even when relationships fall apart, so I’m a little apprehensive to admit that I welcomed him moving away.

I had lived in fear of him taking the boys as he had threatened to, despite knowing that he was neither willing nor capable of raising them on his own. In some of our many confrontations during the separation process, he had invoked the Islamic sharia, which gave custody of sons to the father, threatening to use it to exercise his right to deprive me of the only thing that I could find purpose to live for — my children.

Neither of us had been particularly observant in our faith, but suddenly he had found a purpose for his religion — invoking sharia to keep me married to him and to ensure that, even in his absence, he could exercise control.

He argued that, as we had married in Egypt, we could only get a divorce granted by a sharia court. For a while I believed him, but mostly because I didn’t care enough about the formalities of a divorce to warrant any action.

I was too consumed with trying to raise my boys (and keep them) to worry about the legalities and formalities of divorce. When Sherif threatened to exercise his rights to custody, I called my father and asked him if he was right. My father quietly told me that he was — that in Islam the mother has custody of the boys until they are two years old, then the father is given custody. “But,” I cried loudly, “he doesn’t want them. He never sees them. He’s never done anything for them. How can I agree to that?”

“Go to the courts,” my father advised, “we are in Australia. We live by the law here. Go to the courts, get a divorce and get legal custody of your children.”

As soon as I could afford it, I did.

********

In the five years it took me to gather up the courage and the money to challenge my husband’s power, I researched and met many women who, like me, were separated from husbands who refused to divorce them.

I learned that many of them believed that the only meaningful divorce they could get was from a sharia court. Some had even travelled to countries overseas where they had originally married to seek a divorce from the courts there.

They lived their lives in a kind of relationship limbo — neither married, nor divorced — tethered to men they despised because of an inexplicable loyalty to a system that was neither accessible nor relevant to their lives.

I learned that some women took this as an argument for the introduction of a sharia marriage and divorce system in Australia that would sit parallel to the existing legal system — similar to the beit din or rabbinic courts that oversee divorce proceedings for Jewish couples.

I’ve since watched with curiosity the very public spats between conservative politicians and some Muslim spokespeople about sharia in Australia. I’ve been somewhat amused by the sensationalist headlines spewed forth by current affairs programs, populist columnists and shock jocks screaming, “sharia in our suburbs!”

As a committed secularist, I stand staunchly against the imposition of religion into the laws and governance of the state. As a woman who, once upon a time, was held hostage by a man who argued that I would be married to him till the day I die, I don’t want to see other women go through the same.

If I was to strip away all my personal and political beliefs, I could safely say that I would never have accessed a sharia divorce even if I could have simply because it was the one thing that he wanted and that I could not give him.

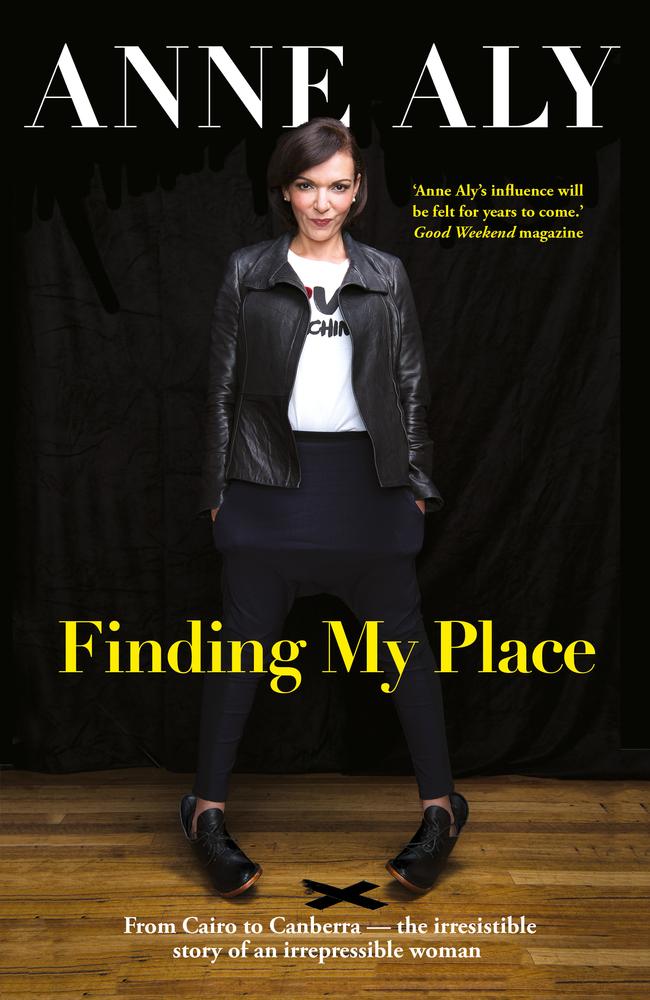

Anne Aly is the first Muslim woman to be elected to federal Parliament in Australia.

This is an edited extract from Finding My Place by Anne Aly (ABC Books) which is available now.