How one woman’s death from Spanish flu caused outrage in Australia

It was the pandemic that killed millions across the world. But when one Sydney woman contracted the Spanish flu, the country was outraged.

In the dying days of the First World War, a new battle was being waged.

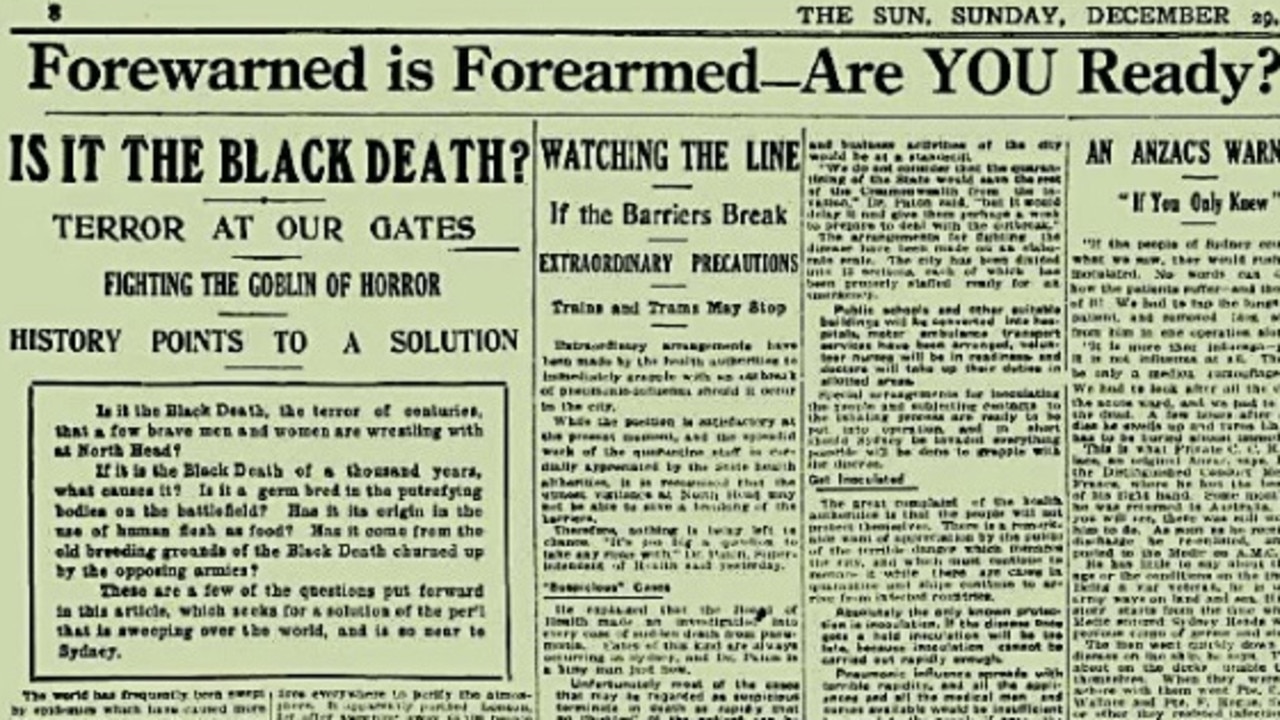

It was October 1918, just a month before the war ended, and most of the world was infected with Spanish flu. Of the populated continents around the globe, only Australia remained free of the epidemic. And it was clear that Spanish flu would be a disaster if it made its way Down Under.

All they had to do was look at other major world cities. Thousands of people were dying every week in places such as London, New York, Barcelona, Vienna and Cape Town. Nearer to home, across the Tasman Sea, New Zealand was already in the grip of the epidemic with people starting to die in Auckland.

As a safeguard, all ships arriving in Australia were ordered into quarantine for seven days. On October 18, the first infected vessel arrived in Darwin — the Mataram, from Singapore — and was immediately placed under quarantine. A week later, on October 25, the Niagara, a Canadian steamer, sailed into Sydney Harbour, flying the dreaded yellow flag of infection.

Sydney blazed with rumours that scores of people had died on its voyage. Actually, the death toll was five, though 155 of the 567 passengers and crew were sick. Niagara was ordered to anchor at North Head, with the infected treated at the nearby Quarantine Station hospital.

The next infected boat to arrive was the Atua, on November 8.

Of the 163 people board, more than half were infected.

So, while Sydneysiders celebrated the end of the Great War on November 11, a new war was raging at the Quarantine Station as staff tried to save dozens of flu victims. Sixteen from the Atua would die.

But for sheer patient numbers, the troopship Medic threatened to overwhelm the Quarantine Station.

The Medic had nearly 1000 people aboard, most of them Australian soldiers and Italian Reservists who had been sailing for the Western Front when the guns fell silent in Europe. Turning around, the boat docked off the shore of Auckland. Even though the city was raging with flu, officers were allowed to go ashore and to return to the ship four days later. Some of these men were infected, though yet to exhibit symptoms.

More than 300 people would become sick with the flu shortly after the Medic reached North Head in mid-November. With hundreds of patients now in the Quarantine Station hospital, many more medical staff were needed.

One of the nurses who answered the call was 27-year-old Annie Egan.

The fifth daughter in a family of nine children, Annie was born in 1891 near Gunnedah, northwest NSW, and raised on a farm called “Roseville”. The Egans had been among the area’s first wheat growers, a tradition carried on by her parents, William and Ellen. The family was also devoutly Catholic. An amiable, happy girl, Annie was schooled by the Sisters of Mercy at the local convent.

While three of Annie’s sisters became nuns, Annie found her calling to be elsewhere, and she went to Sydney to study nursing.

Living with one of her sisters in Annandale, she started training at St Vincent’s Hospital in Darlinghurst in May 1915. A photo of her shows a dark-eyed young woman, smiling warmly in her nurse’s tunic, a cow lick of dark hair curling from her white nurse’s hat. Annie passed her Australian Trained Nurses’ Association exam in June 1918. Proud, she returned to Gunnedah to visit her family, before returning to St Vincent’s to begin practice.

With medical personnel desperately needed to tend to wounded servicemen, Annie volunteered to become a military nurse, likely expecting that she’d be doing her duty at Randwick Military Hospital. Instead, she soon received a far more dangerous mission — caring for sick soldiers at the Quarantine Station.

Annie knew the risks. A Canadian nurse had been on the Niagara, sailing to visit family in Sydney, when the influenza outbreak began on the ship. She volunteered to look after the sick, became infected and died within a matter of days.

Even knowing these dangers, Annie had to be shocked by what she saw when she walked into the Quarantine Station’s Hospital wards. As one of her colleagues would later recall about Spanish flu: “I am sure others will bear me out when I say that it is about the most painful illness known to the medical profession.”

The disease struck with such dizzying quickness that people often collapsed in the street almost as soon as they felt symptoms. Sufferers were wracked with headache and back pains.

They became light sensitive, developed pharyngitis and their temperatures soared to around 40C.

The next three or four days were crucial, particularly for patients who developed bacterial pneumonia. Telltale signs were two reddish spots, one over each cheekbone. Faces flushed dark red, the colour of plums, then turned blue and purple on the way to going black. Feet and hands darkened and these shadows crept along the limbs and across the torso and abdomen.

People could lose their hearing, sight, sense of smell. Insomnia meant even the relief of sleep was denied. Victims bled from the nose and mouth. Teeth and hair fell out. The smell they gave off was like musty straw. Death was usually then imminent — days away at most. Chests distended as lungs filled with blood and froth. People drowned in their own fluids.

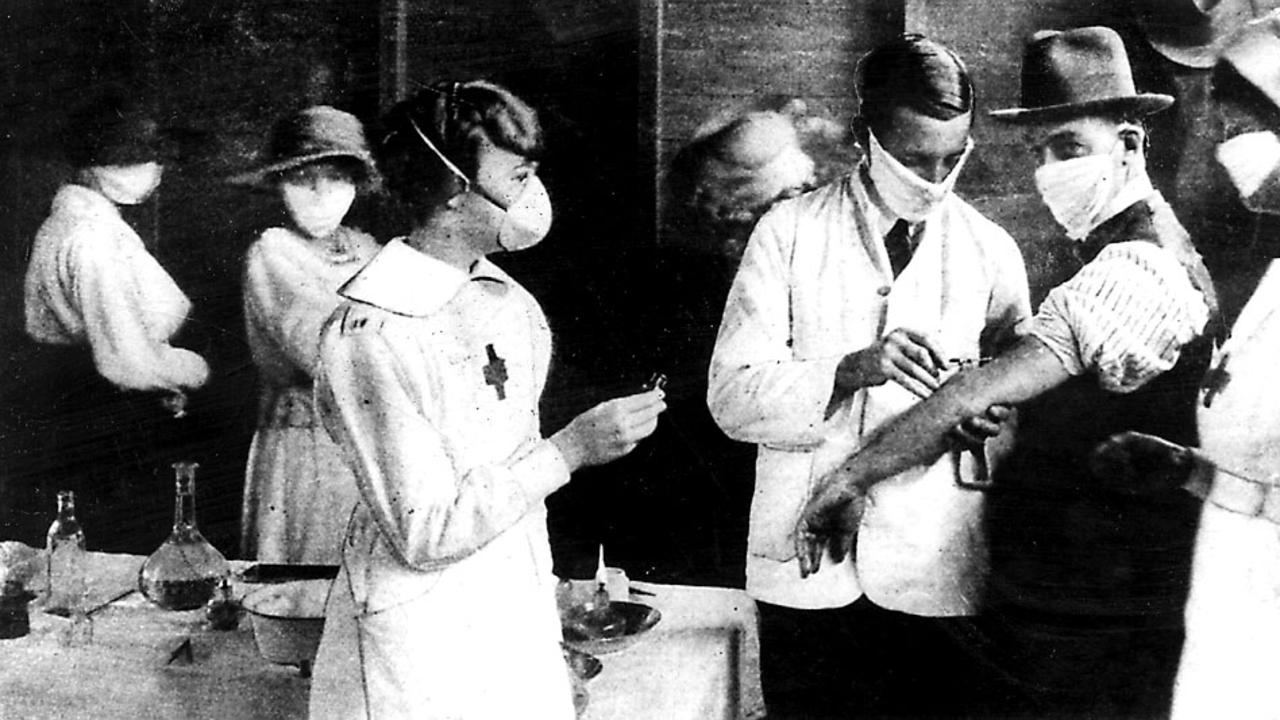

In 1918 antibiotics and antiviral drugs were yet to be discovered, though an experimental vaccine had been developed locally. While such inoculation couldn’t protect against the flu, it was thought effective in helping to protect against secondary bacterial infections. So, with their limited means, medicines and understanding of the flu, Annie Egan and other medical staff at the quarantine station did what they could for sufferers. They gave inoculation jabs and held a “thermometer parade” each morning in which everyone in wards and on anchored ships was tested for fever.

They operated inhalation chambers where patients breathed in fumes from a zinc sulfate solution, which was thought to help sterilise their airways. Similarly, huge autoclaves were used to disinfect clothing, luggage and linen.

Flu sufferers were given painkillers like aspirin and quinine, bathed and cooled, nourished and made as comfortable as possible as the disease ran its course.

To protect herself, Annie wore a mask. But proper care of wearing masks wasn’t observed at this time at the Quarantine Station.

By November 26, 1918, Annie was infected. Her condition — along with that of other patients, including several other nurses — was reported daily in the Sydney papers. At first she was merely listed as “ill”. But as her condition worsened, Annie knew the fate she might face. Six Australian soldiers had died since being brought ashore.

Realising nothing might save her life, Annie’s focus became her afterlife.

Annie needed the spiritual comfort of having her confession heard and, if it came to that, the last rites administered.

“Let me have a priest,” she said. A man of the cloth from nearby Manly volunteered to see her. He realised the risks and was prepared to submit to any regulations even if it meant himself remaining in quarantine. But the federal government, which had control over the Quarantine Station, refused him permission to visit the young nurse.

Letting a priest in, federal authorities argued, risked giving the infection another host and thus prolonging the epidemic. Over the next four days, Annie pleaded — but the government wouldn’t budge.

On December 3, she was listed as “dangerously ill”. Annie was allowed a phone call from the priest at Manly. “I will say Mass for you,” he told her. “You will be all right.”

That afternoon, Annie died.

Bodies were highly infectious so she had to be buried on site. Her funeral service conducted by a Catholic nurse, Annie received full military honours, with a bugler playing the Last Post as troops fired a salute. Soldiers and station staff placed wreaths made from wildflowers on her grave.

When the story of Annie’s last days made the newspapers, there was immediate outrage; not at her death, but at the religious rites she had been denied. On the day she was buried, the Catholic Press thundered: “While the authorities blundered, blustered and bluffed, this girl, who, for conscience sake, was offering her young life to help secure health to the community and her fellow citizens, was callously permitted to pass hence without the consolations of religion and the rites of her Church.”

Two days after Annie died, a Requiem Mass was held at Sydney’s St Mary’s Cathedral.

The congregation of mourners was huge and included her grief-stricken family, friends from St Vincent’s, the city’s Catholic hierarchy and numerous politicians both state and federal. Speaking at the service, Archbishop Michael Kelly called Annie a martyr and railed against what he called the federal government’s “impious refusal”.

From across the country, politicians, judges, clergymen of Christian denominations and even prominent atheists lent their voices to the protest. With Prime Minister Billy Hughes in London, Archbishop Kelly sent a protest telegram to the acting prime minister William Watt. When he didn’t get a reply, the Archbishop took a carriage to the Quarantine Station and demanded admission so he could minister to the sick. He was politely told he’d be arrested if he tried to force his way in.

But the publicity stunt had the desired effect and the government, now copping criticism from all quarters, backed down. From then on, patients at the Quarantine Station would at least have the comfort of their religions.

To hear the rest of the story, go to www.forgottenaustralia.com