How convict Thomas Jeffries became cannibal bushranger

He was known simply as the Monster. And when bushranger Thomas Jeffries was executed, an entire island breathed a sigh of relief. WARNING: Graphic.

WARNING: Graphic

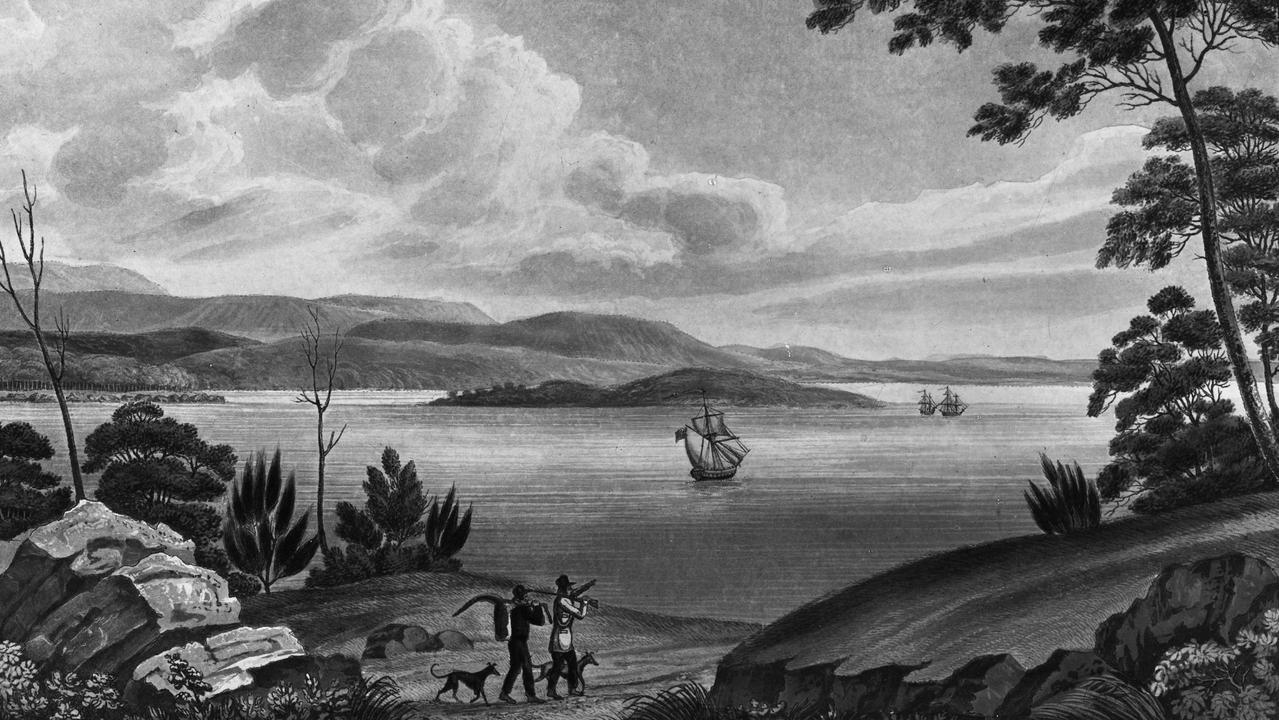

On New Year’s Day in 1826, a woman stumbled alone through the Tasmanian bush, dazed and distraught. It had been a terrifying 24 hours for 18-year-old Elizabeth Tibbs.

Somehow, miraculously, she had survived an encounter with one of the most evil bushrangers in Australia’s history.

Tragically, her five-month-old baby had not. The child had been killed in the most brutal way, beaten to death by the bushranger – simply because having to carry the baby meant Elizabeth struggled to keep up with the outlaw and his men.

The bushranger was Thomas Jeffries. Over the course of his infamous criminal career, he was guilty of serial rape, murder and cannibalism.

He liked to call himself Captain Jeffries, perhaps a nod to his naval roots, or perhaps because he saw himself as more powerful than the law of the land.

But everyone else simply called him the Monster.

Jeffries the child killer

Though Jeffries had lived as an outlaw before – both in Sydney and Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania) – at the time his path crossed with the Tibbs’ family, he had been on the run for around three weeks.

On December 11, 1825, Jeffries along with convicts John Perry and Edward Russell escaped from Launceston Watch House. They spent the next six weeks terrorising the local inhabitants in the north of Van Diemen’s Land.

On Christmas Day, they shot one man they came across in the thigh, then demanded he carry their loaded knapsacks. When he couldn’t, they shot him again and left him to die.

Then on New Year’s Eve, they came across a labourer working on the farm of John Tibbs. John and Elizabeth had been married for less than two years, they’d only lived on the farm for a few months which they rented from John’s father, and had a five-month-old son, John Isaac Tibbs.

The labourer mentioned the farm to the bushranger, telling him that only the couple and a stockman were at home, so Jeffries, Perry and Russell headed there.

They rifled through the house, taking what they wanted, then marched the stockman, John and Elizabeth with the baby in her arms into the bush.

A few years later, in a letter to the Land Board, John Tibbs recounted the events of that day.

“The notorious Jeffries came to my place with two other armed men and dragged your petitioner, his wife with a child at her breast and my assigned servant into the bush,” he wrote.

After meeting others along the way, Jeffries and his men ended up with seven prisoners.

“When about three miles distant from my house they ordered us to stop and then ordered two of the strongest men that they had captured to fall out, of whom I was one,” John Tibbs continued. The other man taken was his stockman.

“We were tied up and ordered to proceed to the side of a steep hill, which I refused unless my wife and child was permitted to accompany me,” he wrote.

“The bushrangers … demanded our names [then] ordered [us] to go on [our] knees and pray as [we] had only a few minutes to live. I reasoned with Perry but without effect.”

The stockman got on his knees, and was shot dead. But John Tibbs remained standing.

“I was saying my prayer, at [the] same time expecting the same fate as my partner, and my poor wife and child in her arms by my side in a state better to be conceived than described.

“Perry then discharged his piece at me, the contents of which lodged in my neck, where part still remains. I then made my escape by throwing myself down the hill in which I received several severe fractures; Perry came up to me again and struck me several [times] with the butt end of his musket. I then made my escape and did not see him more ’til in Launceston Gaol.”

By a miracle, John found his way out and raised the alarm. He eventually recovered from his injuries. Meanwhile his wife and child were still prisoners of the bushrangers.

Elizabeth by this point had been carrying her baby for hours, traversing miles of rough bush. Her speed didn’t suit Jeffries though.

In Jeffries’ own confession, which he wrote in prison in the days before his execution, he said: “We could not get the woman on; we did not know what to do.” He didn’t mention killing her child. He didn’t mention the child at all. Whether that was due to a feeling of guilt or indifference, we will never know.

“Jeffries demanded the child from Mrs Tibbs; the pressed men [prisoners] then went on, leaving Jeffries and one of his associates behind with the child, which afterwards Jeffries murdered,” John Tibbs wrote.

In Perry’s confession, he said: “Jeffries soon after took away Mrs Tibbs’ child accompanied by Russell, and after they had been absent about half an hour they returned without the child.”

When Jeffries came back without the baby, and Elizabeth accused him of murdering her son, the bushranger denied it, saying instead he had sent the child off with one of the other prisoners.

Elizabeth was ordered that night to sleep beside Jeffries. With a history of rape, it is likely he sexually assaulted her, though this is not mentioned in any official reports. The next morning, he let her go.

She found her way home. It was some days later that the baby was found dead. His body had been attacked by wild animals in the interim.

In his confession, Jeffries had a lot to say about his life in England, he gave details on other attacks he made, he even directly spoke of his cannibalism. But of the events of that New Year’s Eve, all he had to say was this: “I can tell no more of that; the great God I hope will forgive the three of us.”

Jeffries the thief

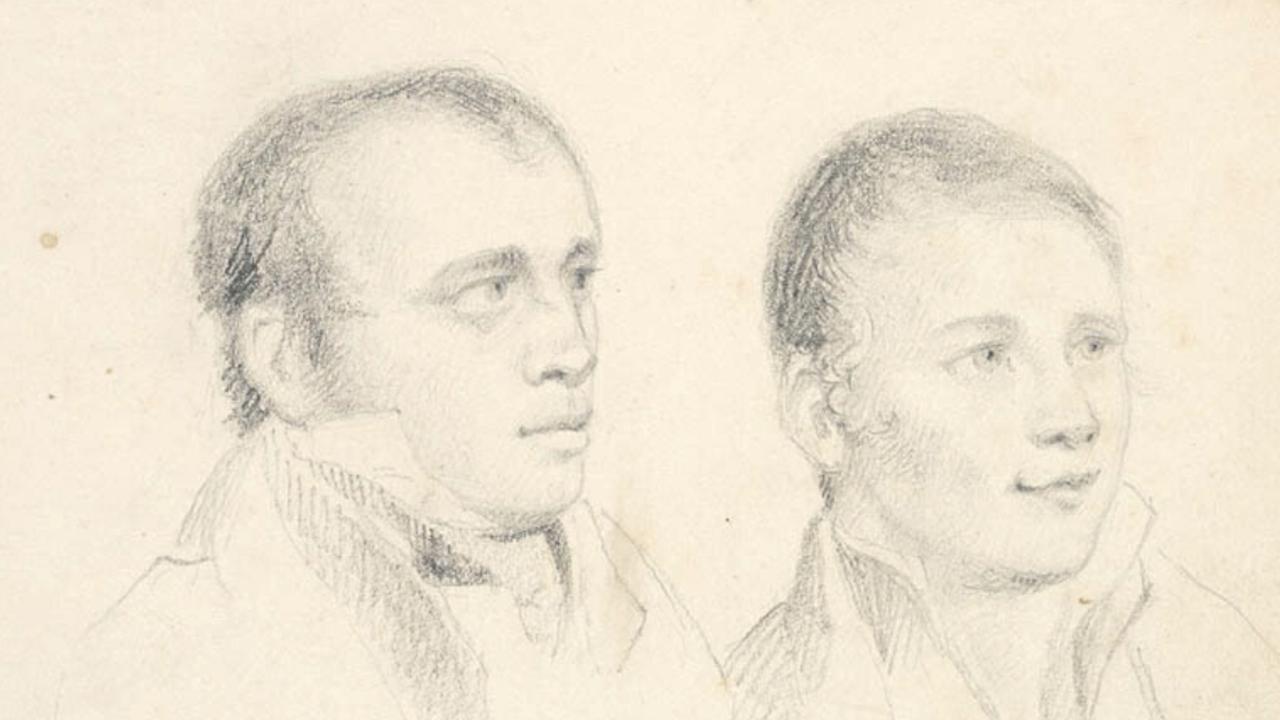

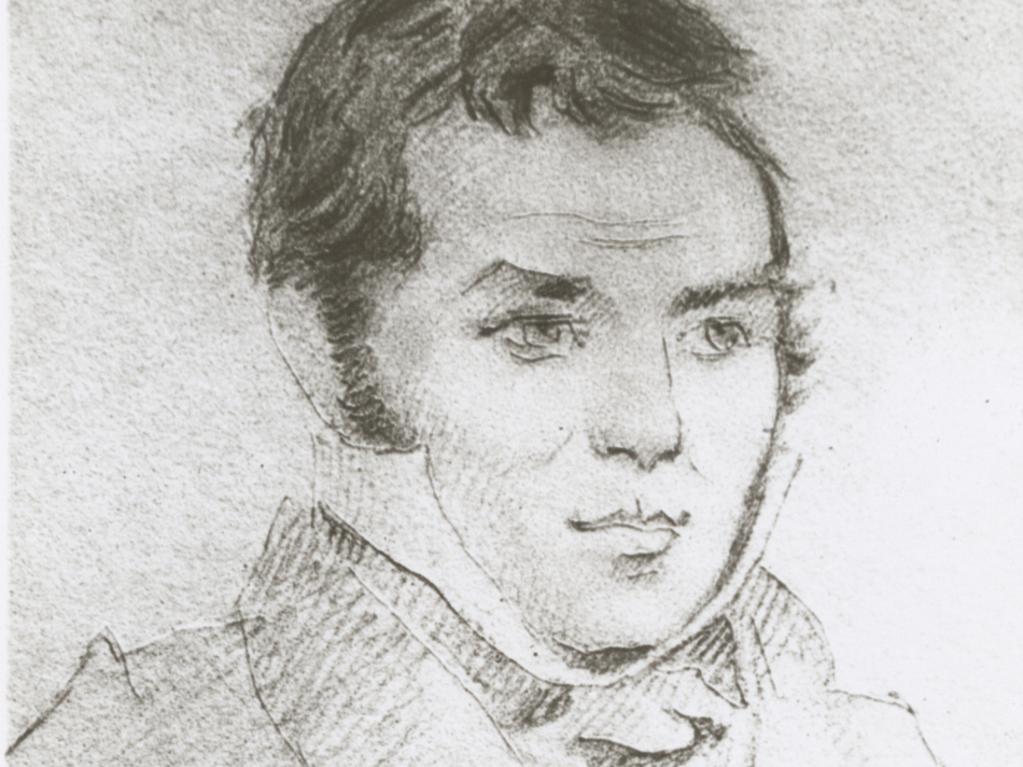

Born around 1791 in Bristol, England, Thomas Jeffries was the son of a butcher. As a teenager, he began his naval career on the man-of-war ship Achille. The ship took part in the Battle of Trafalgar, and it’s possible Jeffries was on it at that time.

After almost five years, he deserted, and after that he quickly became dissatisfied with any new position he tried.

Instead, he became a thief, stealing from his father, his friends and other relatives.

Once he’d pilfered from everyone he knew, he began stealing from strangers and it was a house burglary that eventually saw him sentenced to life transportation to New South Wales.

On the journey out, due to his sailing experience, his chains were struck off and he was put to work on the ship. But once at Port Jackson, it didn’t take long for Jeffries to fall foul of the law again, absconding to the bush with a band of outlaws.

“We did some of the most daring robberies ever were known,” Jeffries wrote of this time. His lawlessness saw him captured and sent to Van Diemen’s Land, where at first he seemed to do quite well.

In George Town, he was appointed as an overseer and constable. But soon it all unravelled.

“I was sent for Launceston, where drink was the total ruin of me,” Jeffries wrote. “I was made watch house keeper, a situation unfit for a drunkard. I tried to leave it long before but could not; it was to my ruin.”

Jeffries the rapist

In August 1825, Elizabeth Jessop was ordered to the watch house by then-constable Jeffries. But when she went, he locked her in a cell, tried to ply her with alcohol, appeared at the cell door undressed and, according to her witness statement, told her: “If you let me sleep with you tonight, I will let you out in the morning before any person is up and will not make any complaint against you.”

Jeffries was known for his ill-treatment of women.

A newspaper article in the Colonial Times dated February 10, 1826, said: “The treatment of many women who had been placed under his charge in the watch house is monstrous beyond description.”

In his convict indent – a record of every time a prisoner misbehaved or offended – as well as the incident with Mrs Jessop, it mentions another time he was caught “taking a female prisoner out of the watch house”. He was given a fine for the offence.

But perhaps the most telling sign of his treatment of women was provided by another bushranger: Matthew Brady.

Jeffries the bushranger

In these early years of the convict settlement in Van Diemen’s Land, there were several bands of bushrangers roaming the countryside. One of the more famous was led by Matthew Brady.

While Jeffries was known as the Monster, Brady was known as the Gentleman.

One time, when Brady and his men took a family prisoner, he sat them down around the dining table, fed them, and even took care of their horses.

After dinner, he collected up their watches, rings, money and other valuables, thanked the family profusely for their hospitality and rode off.

Above all, Brady would not stand for any of his men harming a woman.

Early in Jeffries’ bushranging career, he fell in with Brady. But it didn’t take long for Brady to see how Jeffries treated women – and to banish him from his group.

Brady’s hatred was so intense for the loathsome Jeffries, that when they both happened to be captured around the same time, Brady called to the jailer, saying if Jeffries wasn’t removed from the cell, “he would be found in the morning without his head”.

In the days leading up to their execution, Brady was sent gift baskets and flowers and fruit from his adoring fans. On the gallows, women wept for the Gentleman Brady.

None wept for the Monster.

Jeffries the cannibal

Perhaps the most gruesome part of the Jeffries story was his proclivity for eating his associates. After the Tibbs encounter, the three bushrangers continued their spree, killing Constable Magnus Baker, before heading east from George Town.

By Perry’s reckoning, they were about 50km northeast of Launceston when they ran out of food.

Jeffries had already eaten two of his companions back in Sydney – and it was Jeffries who now came up with cannibalism as a way out of their predicament.

“When we were much exhausted for want of food, Jeffries said to me and Russell, ‘If you like, the first man that falls asleep shall be shot, and become food for the other two.’ Russell and I said, ‘We board it’ – were glad of it,” Perry said in his confession.

“Two days after, we were going up a rocky and scrubby high hill. When we all sat down to rest ourselves … Russell fell asleep. I was sitting close to him. I took a pistol from my knapsack … and shot Russell,” he said.

“He expired without a groan. I took out my knife and cut off about seven or eight pounds of flesh,” he said.

“Jeffries and I ate about a pound of it. I put the rest into my knapsack and Jeffries and I travelled on.”

Jeffries at the gallows

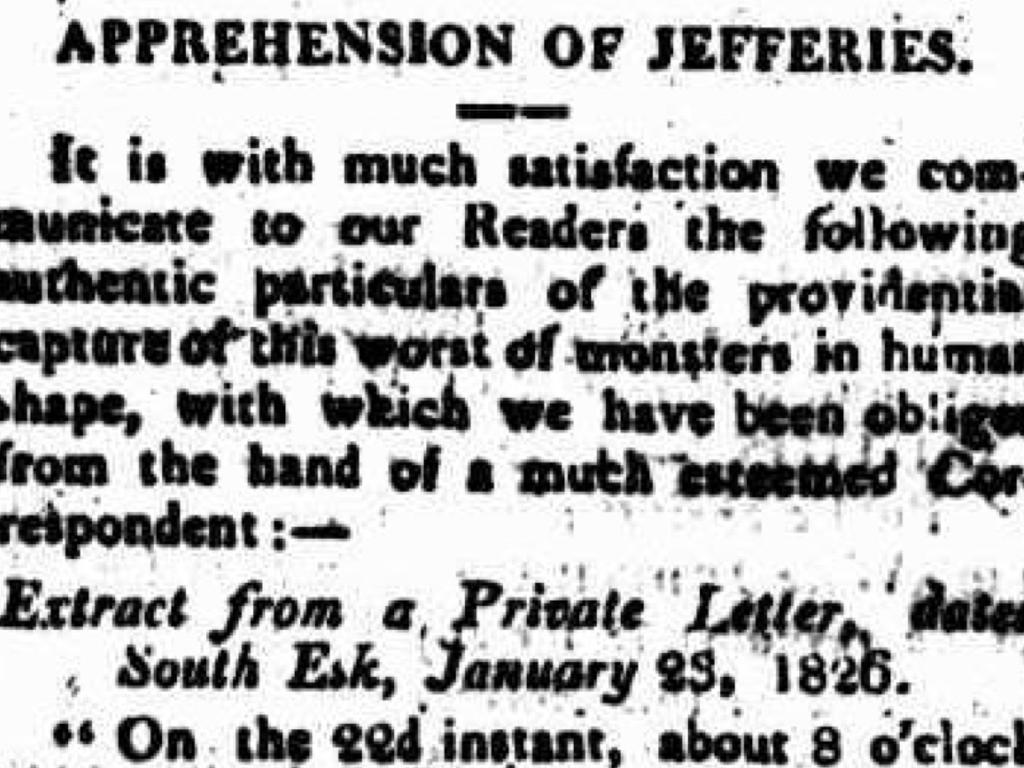

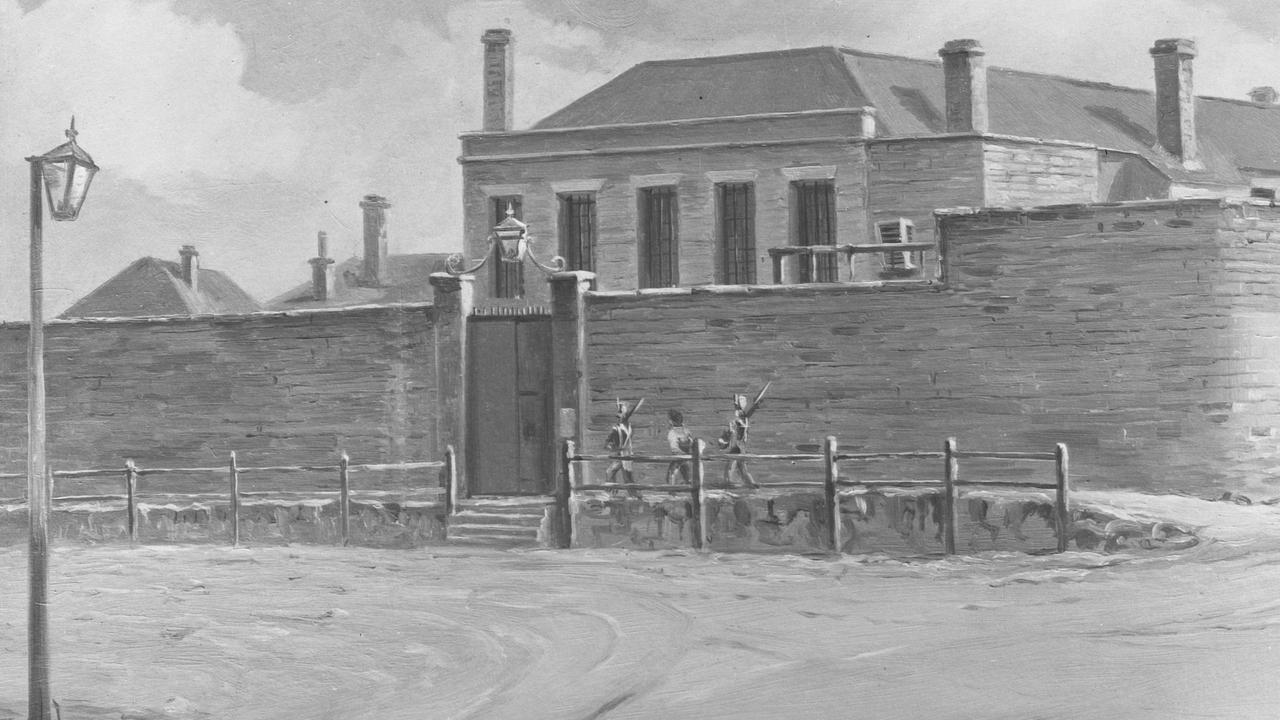

Russell and Jeffries separated soon after. But it wasn’t long before they were both caught. On January 22, 1826, Jeffries was captured near Launceston.

When news spread through the town that he was being brought to Launceston Gaol, the grandmother of the Tibbs baby ran out of her house, brandishing a fork in her hand, and ran up to the man, driving the fork into his thigh as she screamed that he had murdered her grandchild.

Unfortunately she didn’t know what Jeffries looked like and had mistakenly injured a soldier.

But she wasn’t alone in her anger.

The Hobart Town Gazette described Jeffries being brought into Launceston.

“The town was almost emptied of its inhabitants to meet the inhuman wretch. Several attempts were made by the people to take him out of the cart, that they might wreak their vengeance upon him,” it said.

“He entered the town and gaol amidst the curses of every person.”

When asked why he had murdered the infant, “he said that he looked upon every human being as his personal enemy,” according to a report in the Sydney Sportsman in 1911.

During the bushrangers’ trial, though, it was 18-year-old Elizabeth Tibbs who stood up to the men who had murdered her child – and sealed their fate.

“When Mrs Tibbs came into court, and her eye glanced on the insatiate murderers of her babe, she was so affected as to be unable to stand,” said an article in the Hobart Town Gazette dated April 29, 1826.

“Her situation powerfully excited the commiseration of everyone present.

“The bare recital of the dreadful journey which the Monster had compelled her to take with him in the woods, was a painful addition to her sufferings.

“When it was necessary for her to look at the prisoners, in order to prove their persons, the suddenness with which she withdrew her eyes, and the tears with which the effort was accompanied, was an instance of detestation more strongly depicted than any assembly of spectators perhaps ever witnessed.”

On May 4, 1826, Thomas Jeffries was executed at Hobart Town. Standing at the gallows, the crowd was informed by Reverend William Bedford: “The unhappy man, Jeffries, now before you, on the verge of eternity, desires me to state that he attributes all the crimes that he has committed, and which have brought him to his awful present state, to the abhorrent vice of drunkenness.”

Elizabeth and John Tibbs went on to have a daughter the following year. The year after that, aged 21, Elizabeth also died. Her cause of death is unknown.