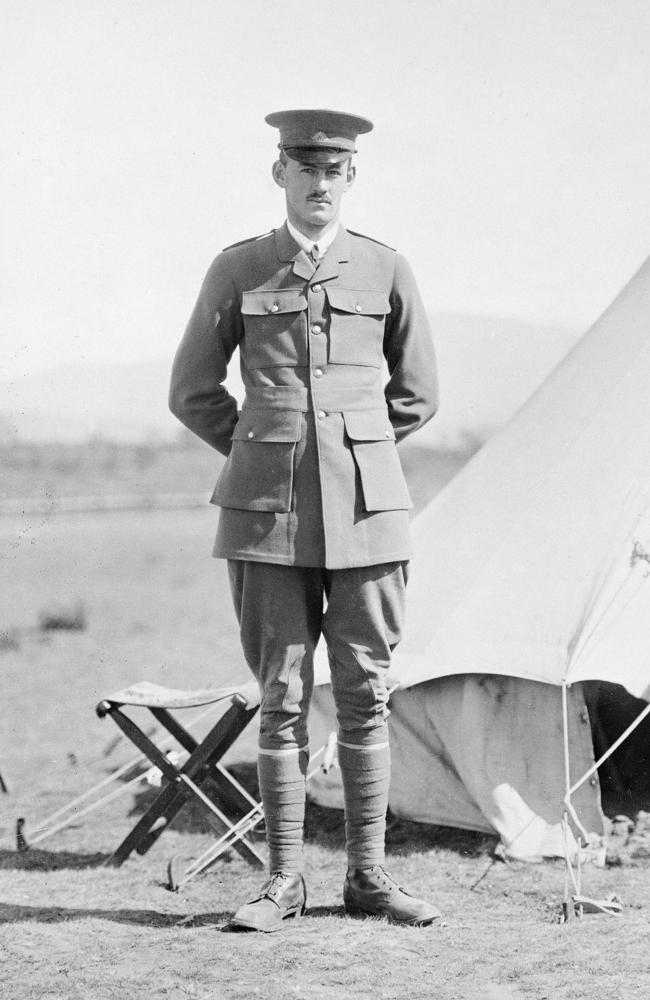

First Anzac Capt Ivor Margetts survived Gallipoli, only to die at Pozieres

A SINGLE white cross stands on a barren landscape after one of the worst battles of WWI. But the story behind it, and the man buried under it, are not easily forgotten.

THE wound was the size of a penny, and it was over his heart.

It didn’t take long for Ivor Margetts to die in the end. He never saw who killed him. A shell burst, a piece of shrapnel, and his part in the Great War was over.

He called to one of his men, Private George McKenzie, who had been with him since they left Hobart, and through every day of the Gallipoli campaign.

Now, cradling him in his arms on a war-ravaged road in Pozieres, France, on July 23, 1916, Captain Margetts told him that he had “got one at last”.

As soon as McKenzie saw the wound, he knew there was no hope.

It didn’t take longer than 20 minutes for Capt Margetts to die. The 24-year-old’s final words to Pte McKenzie were: “If you get through this stink lad, which I hope to the God above you do, let my people know how I got hit and died thinking of them.”

And then he was gone.

Later, Pte McKenzie would write to Captain Margetts’ parents back in Launceston of their son’s death, which was reprinted in Les Carlyon’s book The Great War. He wrote: “There was never a better officer living than Capt Margetts. He was the most popular man in the Batt and he never done a bad turn to anyone since we left Hobart Shore. It is the worst shock the 12th Batt has had since war started. Any one would of gave their life for to save his little toe.”

It was Pte McKenzie who buried his beloved Captain close to where he was hit. It was he who placed the little white cross which draws our eye in this iconic picture.

Two days later, the Germans blazed through and destroyed the cross. Now no one knows exactly where Ivor Margetts is buried.

AN ORDINARY BLOKE

By all accounts, Margetts was a genuinely nice guy. The kind of bloke you’d want to be mates with. And he was my ancestor — my grandmother’s first cousin, making him my first cousin, twice removed. He was a legend in my family. His friends called him Margo, but in my family, he was always referred to as Captain Ivor.

He was tall — 6ft 3 — tanned and cheerful. He grew up in Launceston, the second of five boys, and when war broke out he was working as a school master at a boys’ school in Hobart, keeping the students in line and coaching the sports teams. He was one of the first to join up as war broke out, and the Hutchins school held a party in his honour, the teachers chipping in to present him with a pipe.

“In making the presentation, Mr Bullow spoke of the happy disposition Mr Margetts possessed, and his power of keeping the masters’ study in harmony by his ability for turning everything into a joke,” a report of the party in the Hutchins school magazine of September 1914 said.

“Mr Margetts suitably responded, saying that, if his nature was a happy one, he couldn’t help it, he had been born like it.”

On the weekend, he played Aussie rules. He was as professional as you could be in those days, playing for Lefroy Football Club.

At Gallipoli, he played footy too. One game in particular is described in Les Carlyon’s book Gallipoli. “In December he played Australian football against the 10th Battalion. ‘Beautiful match. Led at three-quarter time, lost by seven points.’”

ANZAC DAWN

Ivor was a month off his 23rd birthday when he joined up to the First Australian Imperial Force (AIF) in August 1914. Starting as a lieutenant, he endeared himself to his men, just as he had gained the love of students and fellow teachers at the school where he worked.

A report in the North Western Advocate in September 1916 said fellow Hobartian, W H Facy, received a letter from his younger brother in which he described Margetts.

“A gentleman and a soldier — and I think that covers a great deal. The men simply worshipped him, and what’s more he had that knack of knowing how to treat his men. He always got the best out of us without any trouble.”

He left with the 12th Battalion on October 20, 1914, headed for Egypt and then Lemnos, unaware that the same time the following year he would be fighting for daily survival in the horrors that awaited them all in Turkey.

His battalion was among the first ashore at Gallipoli on April 25, 1915. Margetts would later write an account of that day. He described how the captain gave the order to man the boats; how the first tow headed for the beach under heavy fire; how just as he was getting the second tow ready to go, a man right in front of him was hit in the head and dropped dead.

Survival was a game of chance — standing a metre to the left or right, leaving a minute earlier or later, was often what stood between you and a bullet.

Ivor’s brother, Ralph, was with him in Gallipoli, but stationed on a medical ship in the Dardanelles Strait. In a letter dated May 5, sent to their parents, which was printed in The Mercury in June 1915, Ralph wrote of word he had received about his brother.

“[Ivor] was well but very untidy — said he was fighting like a wild Irishman, with most of his clothes torn off. I have since heard that Ivor was seen on the beach with what few of his men were left.

“You can’t imagine how pleased I was to hear about him. It was reported on board that he was the only officer left of his battalion.”

He went on: “You should just hear, the naval men who put our men ashore speak of the way our lads charged up those hills! They say it was simply wonderful, and they have made a name for themselves forever.”

Despite many close calls, Ivor survived Gallipoli, where so many others didn’t. But the end of the campaign wasn’t the end of the war for those first Anzacs. France beckoned.

POZIERES

The battle of Pozieres began on July 23, 1916. But for Capt Margetts, it also ended that day.

By the afternoon of July 23, it was reported the northern French village was clear. Ivor went with a small party of men through the village to choose a site for trenches. At around 10pm, a sudden burst of fire from the Germans took them by surprise. A shell burst nearby and a piece of shell hit Ivor in the chest, over his heart. He had survived the whole Gallipoli campaign, to be killed on the first day at Pozieres.

Pte McKenzie told the Red Cross: “The men loved him. I cried like a kid when I found he was dead … I think he went because he was too good for the beastliness of war.”

OUR STORIES

My nana was a cheeky, red-haired 13-year-old when cousin Ivor went to war. We had a picture of him on the bookshelf in our home growing up — a young, smiling man with a pipe in his mouth, the pipe his beloved students had given him, with the hope he would come back to them.

And as Ivor was dying on that road in Pozieres, another young British private with a Royal Army Medical Corps pin on his cap was nearby, working as a stretcher bearer among the mud and devastation, bringing the wounded off the battlefield. His name was John Langford and he was my grandfather. He survived. If he hadn’t, I wouldn’t be here today — or my brothers and sisters, nephews and nieces.

And each Anzac Day, there are countless households around the country also remembering their family members who fought in conflicts across the years.

Time goes on, and the distance to these first Anzac stories becomes greater, but that doesn’t mean they’re forgotten. Stories are passed on and heroes become legends. The passage of time makes them stronger. And in a world of conflict and fighting and fear, we remember those who came before. Lest we forget.