Beatings and torture: ‘I spent five months in solitary confinement’

THE natural beauty of a tiny island in South Africa belies the horrors that took place in its notorious prison.

SOUTH Africa’s Cape Town boasts stunning views of the notorious Robben Island from across the deep blue, shark-infested waters where the Indian and Atlantic Oceans meet.

But the breathtaking sights belie the sheer horrors of the island’s grim past.

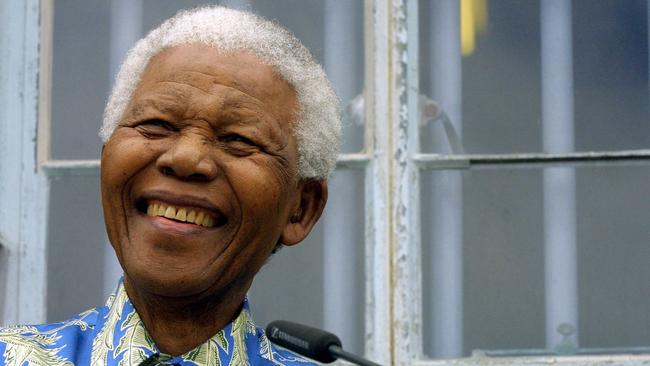

The maximum security prison located on the island, almost 10km from the mainland, is where thousands of political prisoners, including Nelson Mandela, were held captive, tortured or killed during the apartheid era.

Inmates endured regular beatings and extreme torture at the hands of sadistic guards whose tactics went largely unchecked. Black prisoners were subjected to the worst treatment in what has been referred to as “the Alcatraz of South Africa”, according to former inmate Sipho Msomi.

Mr Msomi, who spoke to news.com.au on Robben Island, was one of six young organisers for the African National Congress (ANC) arrested as a group for fighting apartheid in 1984.

They each went on to do years behind bars on the island. It was an extraordinary test of resilience — that many of South Africa’s towering figures in the anti apartheid struggle endured — but not all of them made it out alive.

Conditions inside the prison were tough. Inmates weren’t given shoes or sufficient clothing. Many were forced every day to do hard labour in a limestone quarry under the glare of the searing African sun. At night they slept on the stone floor of their tiny cells or on rickety spring beds in larger, overcrowded dorms. But those hardships all paled into comparison with solitary confinement, the punishment inmates feared most. It didn’t take much to end up there: being caught reading a newspaper or political literature, singing songs about freedom, organising card games or working too slowly were just some of the punishable ‘offences’.

‘EXTREME FORMS OF TORTURE’

Mr Msomi spent a total of five months in solitary confinement in a single 8x7 foot cell where the torture inflicted on inmates was so extreme that it often proved deadly.

“When we were arrested in late January 1984 we were six,” Mr Msomi told news.com.au.

“But coming out of that solitary confinement we were five.

“Because one of us, as we always knew would happen, was tortured to death at age 22 by security police.”

For those who survived the torture it “always came hand-in-hand” with long hours of being questioned and interrogated by South African security police, according to Ms Msomi.

“You would always be fearing for your life because of the extreme forms of torture in solitary confinement,” he said.

“You would always be feeling like ‘these guys may simply kill me whenever they want to because they’ve done it before with many other people.”

The mental torture was often just as severe as the physical.

“The way the prisoners were treated on the island was to demoralise them, to kill the human spirit,” Mr Msomi said.

Prison guards would cut out sentences or paragraphs from letters addressed to inmates from loved ones before delivering them to their cells. Inmates referred to them as “window letters”.

The only time prisoners were given their letters in full was when they received bad news, such as a death in the family “because they knew that it was going to hurt them”.

Additional restrictions designed to cause distress would be placed on prisoners in solitary confinement.

“Generally privileges like receiving letters would never be allowed, getting visitation rights would never be allowed, talking to each other as prisoners would never be allowed, getting a simple thing like a book would never be allowed,” Mr Msomi said.

“It was so you really feel the sense of being isolated.”

Prison food — which mainly consisted of rice — would be drastically reduced as a form of punishment.

“They would systematically starve you by reducing your diet,” Mr Msomi said.

“There was always a lot of mental strain in solitary confinement ... it was always a very difficult and stressful experience.

“But as prisoners we would always be defiant: We would talk to each other and we would sing freedom songs, even though that was not allowed.”

LIFE INSIDE ROBBEN ISLAND MAXIMUM SECURITY PRISON

A typical day in the prison saw many inmates forced to do labour work in the island’s limestone quarry, from 7.30am to about 4pm, seven days a week. Armed authorities stood guard on the boundaries of the quarry. To avoid them, prisoners, including Mr Mandela, were forced to “share buckets as a toilet” inside a cave. The cave came to double as a learning centre known among inmates as ‘the Robben Island University’. It was there that the most prominent prisoners would speak freely about democracy, socialism and political protest.

“There were very few days when we were locked in the cells the whole day,” Mr Msomi said.

“I don’t think there were more than 10 days. We were always taken out to work.

“We were not happy we had hard labour but we welcomed any other kind of work.”

When they returned to their cells, some inmates would work in the prison kitchen. It was an opportunity to engage with other prisoners and exchange contraband.

“They were very influential circulating newspapers,” Mr Msomi said.

“If caught they would sentence you to solitary confinement or sentence you to one or two years more.”

Senior leaders took on the role of fighting for all prisoners’ basic human rights. Sometimes they were successful, but most often they were not.

Despite being pushed to the brink and back again, Mr Msomi said he was one of the “lucky” ones.

“Most did at least 10 years and others got 45, 47 or life sentences,” he said.

“So for me five years wasn’t bad.”

It’s that sheer triumph of the human spirit which has become globally synonymous with Robben Island’s former prisoners.

While Nelson Mandela — who served the first 18 of his 27 years sentence in Robben Island prison — was undoubtedly the most celebrated inmate he was also one of three who went on to become President of South Africa.

South Africa’s current President Jacob Zuma was also held captive in the prison — for a decade. Mr Zuma is currently at the centre of national backlash over the country’s economic crisis and accusations of government corruption. Kgalema Petrus Motlanthe served as president from 2008-2009, more than 20 years after he was released from Robben Island.

“We were a community of people who ranged from the totally illiterate to people who could very easily have been professors at universities,” Mr Motlanthe once said.

“We shared basically everything. The years out there were the most productive years in one’s life, we were able to read, we read all the material that came our way, took an interest in the lives of people even in the remotest corners of this wold. To me those years gave meaning to life.”

Other notable political prisoners included Robert Sobukwe, who became president of the Pan-Africanist Congress in opposition to apartheid in 1959, spent six years in solitary confinement.

His imprisonment was renewed annually by the Minister of Justice in a procedure that became known as the “Sobukwe clause.” The clause was never used to detain anyone else.

When former US President Barack Obama visited Robben Island during his term, he and then-First Lady Michelle Obama wrote in a guest book: “On behalf of our family we’re deeply humbled to stand where men of such courage faced down injustice and refused to yield. The world is grateful for the heroes of Robben Island, who remind us that no shackles or cells can match the strength of the human spirit.”

Ms Msomi was released in 1988 and today conducts tours through the prison, which has been operating as a museum since 1996 and is now a UNESCO World Heritage site.