Bali Nine executions: Does the death penalty stop crime?

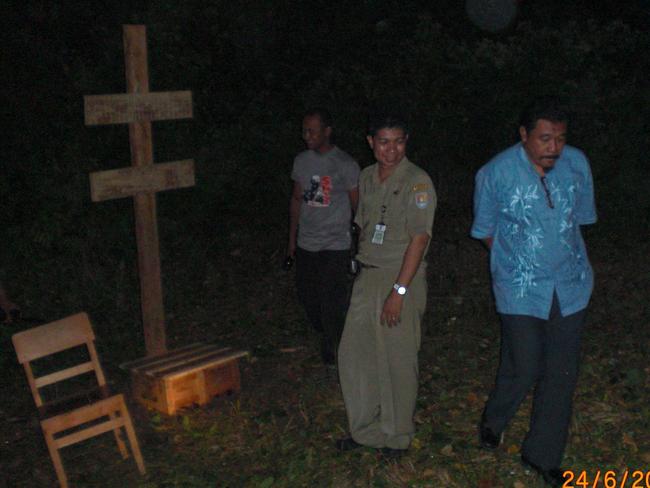

THESE men will be taken to a field, strapped to a cross and shot to death. The death penalty is common throughout the world, but does it actually work?

THE day is imminent.

They will be taken from their beds under cover of darkness, escorted to a secluded field, strapped to a wooden cross and shot to death.

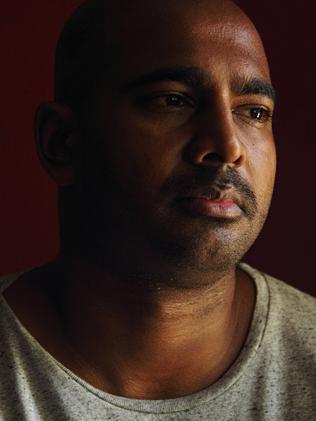

Yesterday Bali Nine death row inmates Andrew Chan and Myuran Sukumaranr learned their final judicial review had been rejected. Their fate is now sealed.

All reports suggest that the two Australians — who were convicted for their part in a plot to smuggle more than 8kg of heroin from Indonesia to Australia — are repentant for their crimes and are now reformed.

Yet, they are marked to be executed by firing squad with the next batch of criminals.

Given that they have evidently learnt from their mistakes and turned their lives around, why are they being killed at all?

RELATED: Grim execution awaits Bali Nine Australians Andrew Chan and Myuran Sukumaran

RELATED: Bali Nine drug smuggler Andrew Chan’s powerful message to Australians

Indonesian law expert Professor Tim Lindsey has shed light on the science behind the death penalty today and says the research is conclusive: There is next to no evidence anywhere in the world that the death penalty effectively deters crime of any kind.

“The overwhelming evidence around the world is that imposing the death penalty has very little effect on the extent to which a crime was committed,” Prof Lindsey, of the University of Melbourne, said.

“It doesn’t act as an effective disincentive in any case. That’s been proven in locations around the world. It doesn’t have any discernible impact on stopping those crimes occurring, which is the tragedy of the whole thing.”

Prof Lindsey said use of the death penalty had more to do with politics than any real desire to reduce crime.

He said the fact that because death penalty determinations were shared between the courts and law makers, they “always became extremely political”.

“Where the life of the subjects is involved, lawyers will push boundaries, and that’s certainly the case in Indonesia at the moment,” he said.

“It has more to do with the political tension of the moment than the merits of the case.”

Indonesia has hastily ramped up the execution of its criminals since the election of its new president, Joko Widodo. Six death row inmates have been killed in the country this year alone and another 11 are in line, including Chan and Sukumaran.

“Indonesia has not been one of the more aggressive users of the death penalty — that honour goes to Singapore and Malaysia — but that may be shifting,” Prof Lindsey said.

“Although it’s been legally ineffective as a response to rising drug use, (Indonesia) now wants to develop a reputation for being as tough on drugs as Singapore and Malaysia.”

Prof Lindsey said Mr Joko’s rival in last year’s election had put a lot of pressure on him to appear tough on crime.

And public opinion is on his side.

“Drug offenders are seen as mass murderers, along with terrorists … You could say most Indonesians certainly support the death penalty for those offences. A small minority are uncomfortable,” Prof Lindsey said.

Psychologist Jeffrey Pfeifer, of Swinburne University, said the US’s appetite for capital punishment excused other countries for continuing the practice.

“All empirical evidence indicates it’s not a deterrent … but there’s a split between the hard science and the political spin,” he said.

“One of the things that strikes me is the lack of attention placed on the US system, where death occurs almost weekly, if not daily, in that country but it seems to me that it flies under the radar.”

As an example, a man is scheduled to be put to death today in Texas, a state with a long history of execution.

Texas is but one of the US’s 32 out of 50 states that imposes the death penalty.

Debate is raging in the US at the moment about favouring firing squads over other means of killing criminals because it is less expensive than lethal injections or the electric chair. There is also discussion about whether 18-year-olds with the mental age of a 16-year-old should be executed.

“As a Canadian, and I’m sure Australians would feel the same way, I think it’s a strange debate to be involved in,” Assoc Prof Pfeifer said.

He also said the US system was psychologically “fascinating” because it is the jury’s job to decide whether a convicted criminal should be put to death or not.

“It’s a fascinating possibility that we can study (but) as a human being, I’m appalled that people are put into that position … it’s horrific,” Assoc Prof Pfeifer said. “You can only imagine the amount of stress that puts people under.”

He said Hispanic and African American people tended to be over-represented when death sentences were handed down in the US.

Assoc Prof Pfeifer said there was even a been a push in some conservative states to extend the death penalty to crimes where a death from drugs was involved.

Meanwhile, three former Indonesian judges have joined a chorus of criticism over the country’s death penalty regime, saying the executions won’t drive down drug crime.

“It isn’t effective in law enforcement, that’s a fact,” said Maruarar Siahaan, who was on the constitutional court panel that heard the 2007 appeal of Chan and Sukumaran.

“As long as there’s continuing weak law enforcement, there will always be continuing drug crime. When the opportunity to escape detection is high, the threat of the death penalty won’t scare those who are in business of drugs,” he said.

“In the future, there’s got to be an ideological platform for the state where we follow the global trend (away from the death penalty).

“We can no longer rely on the idea that this is for a deterrent effect.”

Indonesia ended an unofficial four-year moratorium when five prisoners were executed in 2013.