Australia’s ‘unclaimed persons’: what happens to those who die alone?

THEY are unclaimed and unidentified. So what happens to the bodies of many Australians who die with no next of kin or known identity?

YOU live as long as you are remembered.

It’s a sentiment that brings hope of eternal life to some but means little for the many others already forgotten by the time they draw their last breaths.

A person dies on average about every three minutes in Australia.

Most of those people will be celebrated at funerals and mourned long after by their family and friends. Flowers will be laid. Photos of their once smiling faces framed and displayed. Their names will be spoken through tears and funny stories told of times past. They will be thought of on ordinary days and sentimental ones; birthdays, Christmases and anniversaries. Their belongings will be held close by surviving loved ones as if each item was the last tangible piece of them.

But that’s not how the story ends for everyone.

There are hundreds of ‘unclaimed’ bodies left in morgues across the country every year.

A body becomes classified as “unclaimed” when no family, friend or community member comes forward to organise their funeral and police can’t identify a next of kin. The names of the unclaimed bodies are often known to authorities but a minority are not.

The bodies can be stored in morgues for months, or even years, depending on inquiries made to contact family and friends.

The unclaimed bodies are typically elderly people without children who have outlived a spouse and siblings; immigrants; the poor; homeless and others estranged from their families.

If they remain unclaimed, the state coroner will release the body to a funeral home with a government contract.

The Queensland Department of Justice and Attorney-General is required to provide a “simple burial or cremation” to any deceased person whose assets cannot cover the cost of their funeral and whose relatives and friends also cannot pay.

The state’s Burials Assistance Act 1965 states that funeral directors must provide “a properly made, conventionally shaped, stained and suitably lined coffin”.

They are to conduct the funeral “in a proper and respectful manner” and provide either a gravesite or crematorium service.

In 2012, there were 385 cremations or burials under the Burials Assistance Scheme at a total cost of more than $600,000.

A NSW Health spokesperson told news.com.au the Local Health Districts were responsible for the processing and payment of destitute burials and cremations in their district.

Rookwood Memorial Gardens and Crematorium operations manager Kevin Morgan said paupers’ funerals were “just a normal service people can attend if they wish”.

“Sometimes there’s nobody that attends,” he said.

“If you were standing in our carpark you probably couldn’t tell the difference between a normal funeral and a destitute person’s one.”

An unclaimed person’s final resting place is dependant on instructions from “the applicant” — usually a funeral director — but most will end up “with their ashes scattered in the gardens or buried in an unmarked area”.

Mr Morgan said the bodies were buried unless the deceased’s identity is known and they signed a form when alive to authorise and request cremation.

‘WHAT WILL HAPPEN WHEN I DIE?’

Mr Morgan told news.com.au that most pauper graves had “no headstone or anything” and were located in a grassy public section area of most cemeteries. Some are sporadically marked with wooden cross, sticks or stakes with items including a flag on top.

He said there were 121 state-funded cremations of destitute and unclaimed persons at Rookwood Cemetery last year.

Northern Territory Detective Acting Senior Sergeant Tony Henrys told news.com.au there were “11 unclaimed bodies in the NT — eight in Darwin and three in Alice Springs — since May 2016”.

“There are no known long term unclaimed bodies,” Sen-Sgt Henrys said.

In February 2015, the NT News revealed that the bodies of 17 babies remained unclaimed in the Alice Springs Hospital morgue — some had been there since October 2014.

A spokesman from the Central Australia Health Service would not provide the causes of the deaths, but said the hospital was in the process of developing a policy for the management of the “unclaimed deceased”. He told the ABC there was no defined time limit for how long a body would stay in the morgue.

There were 159,052 registered deaths in Australia in 2015, according to the Bureau of Statistics.

Several charity organisations told news.com.au they “always assist with funerals” but that many people were still worried about dying alone.

Matthew Talbot Hostel Pastoral Care Officer Elizabeth Lee said she was often approached by elderly people with no next of kin who worried about what would happen to them.

“One man ... recently asked: ‘What will happen when I die? ‘my parents are both passed and I have no contact with my brother’,” Ms Lee said.

“I was able to assure him that we could and would treat him with dignity both in life and death.”

In April this year, two men who were long term residents at a Sydney homeless shelter and had no next of kin, were buried together after a joint state-funded ‘paupers’ funeral’ at Rookwood Cemetery. No one who attended the service knew or had ever met the men. A bishop conducted the service which was organised by a funeral home and St Vincents de Paul.

Mark Gerhard of Catholic Cemeteries and Crematoria gave a touching tribute to them.

“We never met you; never looked into your eyes, shook your hand, smiled, laughed or cried with you. We never knew you … but we know you,” Mr Gerhard said at the service.

“We know that you once laughed, dreamt, hoped and sought love. We know that you felt success and achievement, loss and failure. We know that you were hurt and that you probably hurt others on occasion as well.”

“You probably loved ice cream and hated vegetables. Enjoyed a beer or two, a chat, a good yarn and a joke.

“We hope that in your life you were loved by someone special to you. That you were held, shown off and boasted about by proud parents or grandparents. We hope that a wounded knee or heart was met with love, care, hugs and understanding. We hope that you found true love and were truly loved in return.

“Whatever the specifics of your lives which we do not know, we know you. You are us and we are you. Our humanity has bound us from time immemorial and will bind us forever more; in pain, in suffering, in hope, in love in truth and in life.”

The two friends were cremated and buried together on the new ‘Charles O’Neill Walk’ in the St Vincent’s de Paul Society section of the cemetery.

JOHN AND JANE DOE’S

In the cases of unidentified deceased people, they are always buried, according to a Rookwood Cemetery spokeswoman.

“It’s so they can be exhumed later if someone comes forward to identify them,” she said.

“There’s a particular area we put those bodies in. You’ll find people also who can’t afford funerals.

“The funeral directors would come to us to organise a burial then we conduct the burial as an initiative of Rookwood.”

A spokesperson from the Coroners Court of Queensland told news.com.au there are “currently 101 unidentified matters with the Coroners Court of Queensland (CCOQ)”.

The figure includes both unidentified deceased persons and unidentified human remains recorded

prior to and since the introduction of an electronic case management system in 2007.

Northern Territory Detective Acting Senior Sergeant Tony Henrys told news.com.au that “at present the NT has 94 unidentified sets of unidentified human remains”.

The Aboriginal Areas Protection Authority has deemed at least 60 sets of the remains to be of Aboriginal origin.

“Where it most likely the skeletal remains have been disturbed from a traditional burial site the remains will be returned to local custodians or left at the discovery location and recorded,” Mr Henrys said.

“Numerous skeletal remains are located in the NT each year particularly in coastal areas after severe to moderate weather events. Further; with continuing development and access to remote areas more traditional burial sites are disturbed by visitors.”

NT Police launched the Cold Case Task Force (CCTF) “to accurately record the discovery of unidentified human remains”.

“This work is ongoing but will eventually provide a comprehensive database of unidentified human remains across Australia,” Mr Henrys said.

“Further investigation and advances in technology have allowed for the identification of a number of UHR since the CCTF was formed.”

Elite Funerals NSW manager Scott Rennie said it was rare for a body to “show up without a name” but in most circumstances it would be buried with a number.

“They get a number on their gravesite rather than a ‘John or Jane Doe’,” he said.

A spokeswoman for NSW Coroner’s Court told news.com.au “if investigations have been completed and fail to identify the deceased the remains are eligible for a funeral without funds”.

One funeral home director, who spoke on the condition of anonymity, told news.com.au that many unclaimed and unidentified people “fall through the cracks” and end up in “communal pits because there is no one to fight for them”.

“That has been going on for yonks,” he said.

STREET KIDS DUMPED IN UNMARKED COMMUNAL GRAVES

In the mid 1990s, several deceased street kids were reportedly unceremoniously disposed of in unmarked communal graves in Victoria. “People still care more when a horse falls and breaks a leg than when someone with nothing dies,” social campaigner Les Twentyman said of the incident in 2014.

Members of the Victoria crime identification squad have previously used morgue photographs and hi-tech facial reconstruction programming to reveal what unidentified people looked like, before their deaths. In 2009, Victoria Police released the computer-generated images to media in a bid for someone who knew them to recognise them. Their DNA was recorded in case a family member later came forward. The dead were later buried in paupers’ graves.

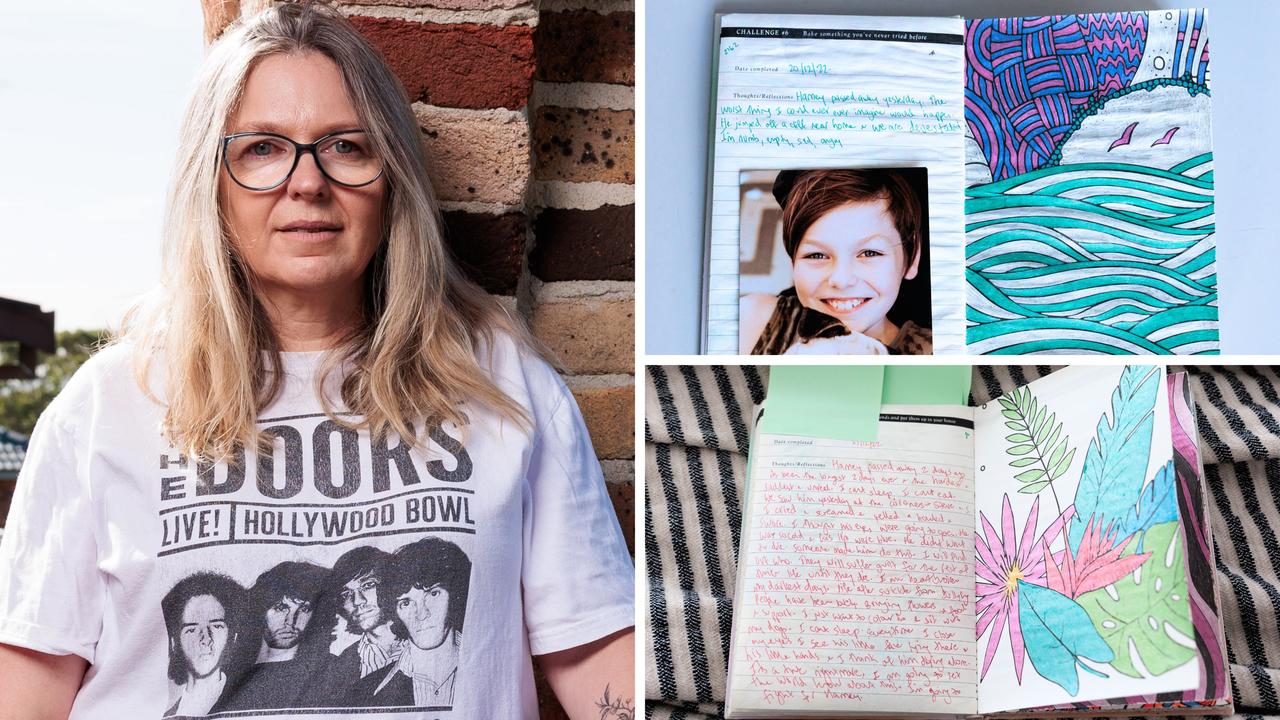

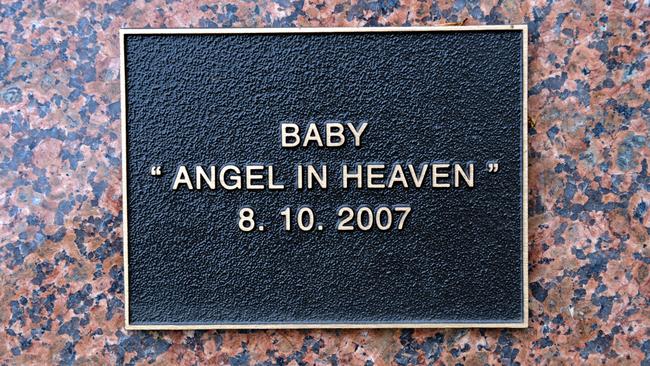

BABY WITH NO NAME: “ANGEL IN HEAVEN”

In Adelaide, a tiny grave bore no name and no epitaph — just the words “Unknown Male Infant” for a baby boy who’d had no life at all.

For the grandmother of a baby buried nearby, it was simply unacceptable; the infant, found stuffed in a sanitary bin in toilets at the city TAFE campus, deserved better than those three cold words. “Baby Angel in Heaven”, as the grave now proclaims, was dead for up to a week when a cleaner found him on October 16, 2007.

The efforts to identify the baby and his mother — which were ultimately unsuccessful — meant the child was not able to be buried until February 2008 in a ceremony organised by the Department for Families and Communities funeral assistance program.

Since 2010-11 — when the South Australia State Government started keeping statistics — the bodies of 53 people have remained unclaimed by family, and their funerals organised by strangers and funded by the Government, the Adelaide Advertiser reported last year.

Their resting places were marked by a name and date punched on a plaque, not much larger than an envelope. There were no heartfelt messages of love or sorrow.

THE SOMERTON MAN

Among older unidentified pauper graves is that of the Somerton Man in South Australia. His epitaph reads: “Here lies the unknown man who was found at Somerton Beach 1st Dec. 1948”.

The mystery first came to attention at 6.45am on December 1, 1948, when two jockeys found the body of a man slumped against a sea wall on Somerton Beach in Adelaide.

Despite the warm weather, he was dressed in an expensive suit and tie but the labels were removed from his clothes. A half-smoked cigarette rested on his shirt collar. There were no signs of violence to his body, no signs of a struggle. The sand around him was dry and undisturbed.

The pathologist was unable to establish a cause of death. He suspected the man had been poisoned but found no trace of poison in his system. The case of the Somerton Man remains one of the state’s most enduring mysteries which has ensured that — while no one knows who this man was — he will long be remembered.