Special biscuits, breakfast TV and endless escape plans — Ivan Milat’s secret life in Supermax

Special biscuits, breakfast TV, endless escape plans. This is what serial killer Ivan Milat’s life was like in Supermax before his death.

EXCLUSIVE

Its infamous serial killer inmate described a cell in Unit Nine of Supermax prison as not unlike an apartment, where he could watch breakfast TV, eat his special biscuits and write hundreds of letters.

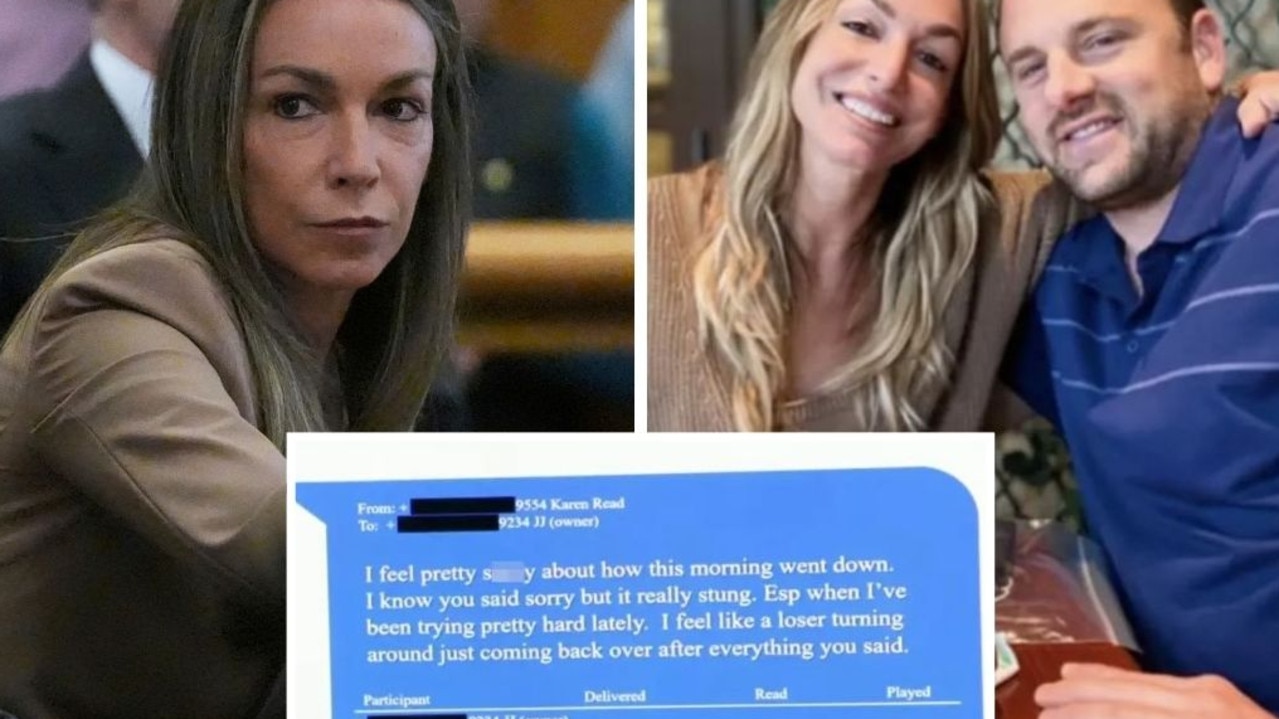

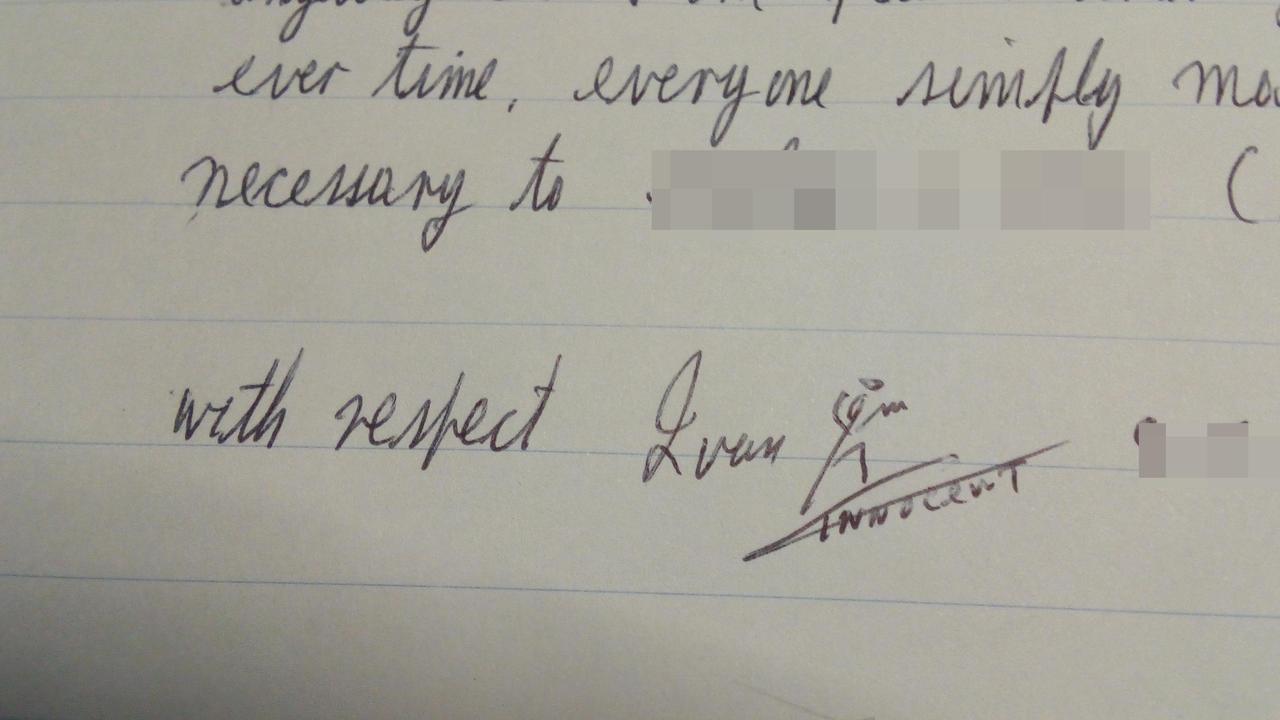

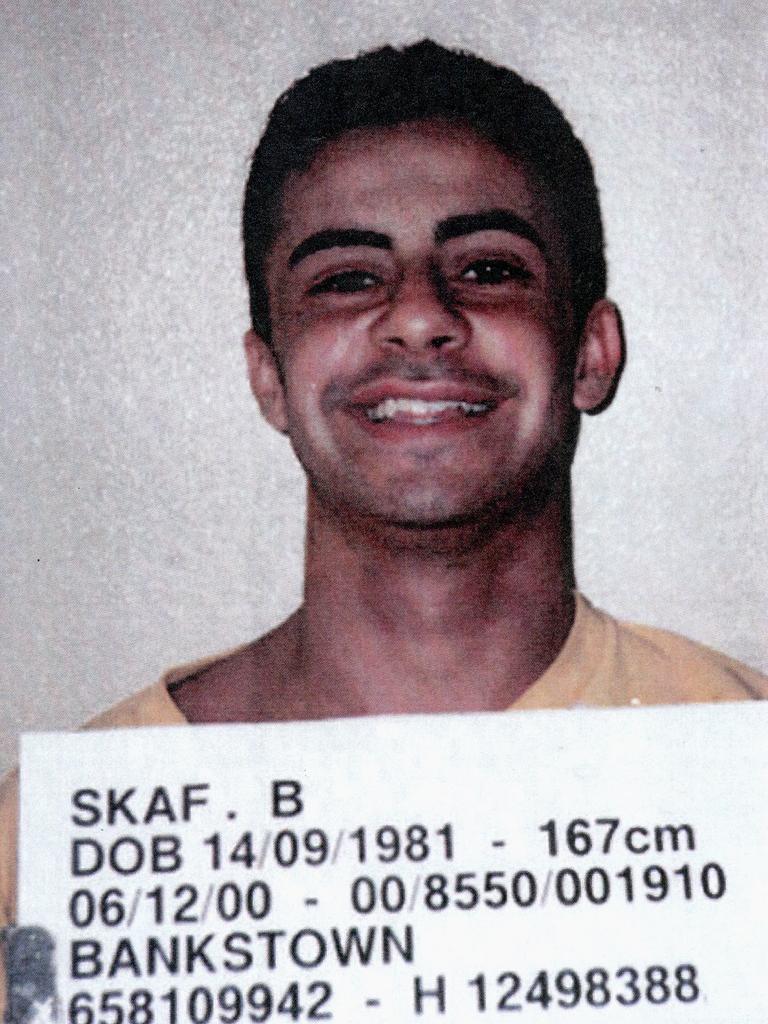

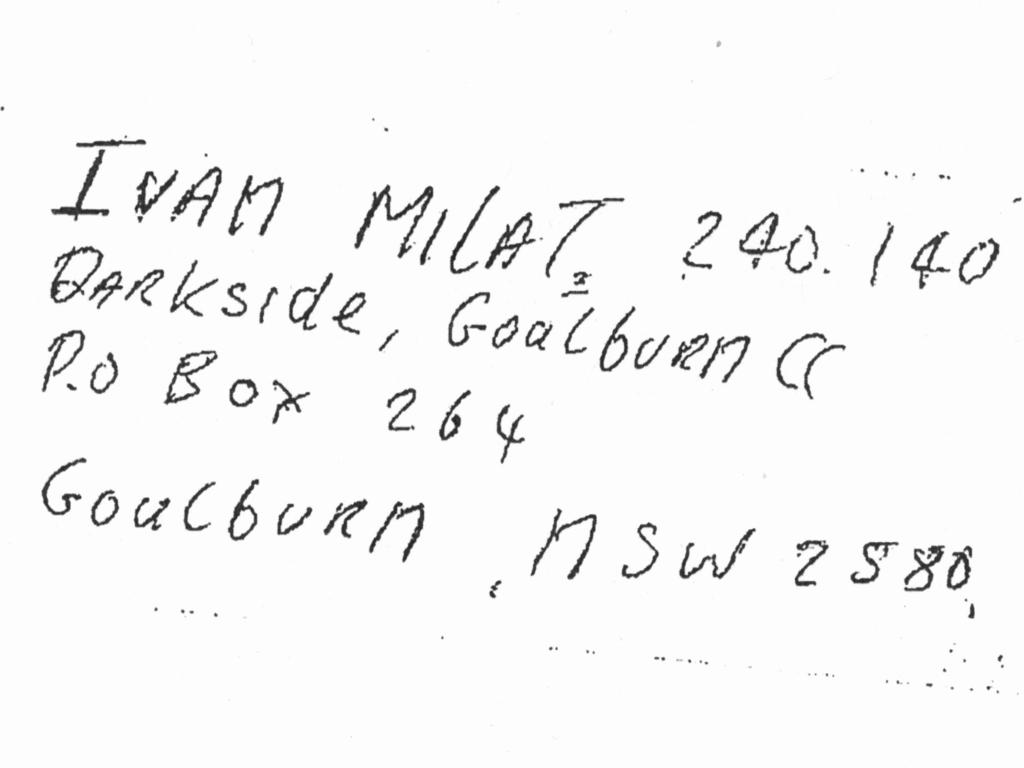

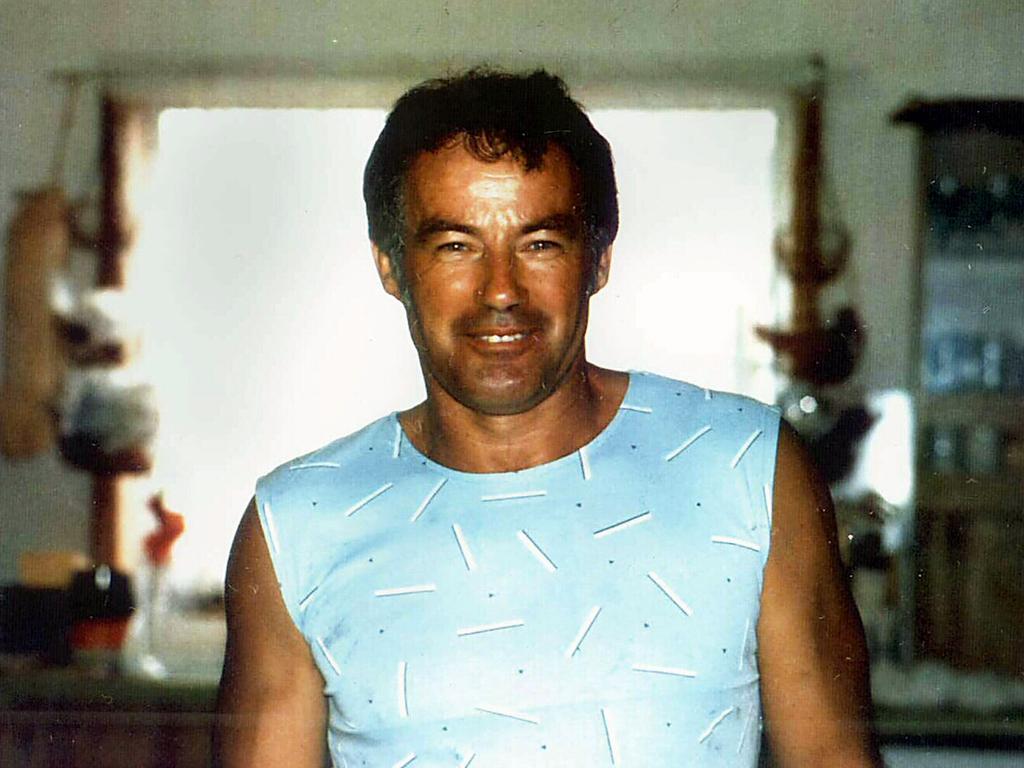

Inmate 240140, better known as Ivan Milat, always signed off his letters — whether they be to friends, the premier or the High Court of Australia — with his signature portrait.

A stick figure with a halo, it represented himself, Milat the innocent man, and often had the word “INNOCENT” written alongside it.

In the Supermax cell that was his home for almost 18 years before his death Sunday morning, Milat was always plotting his escape.

In between the special chocolate biscuits he ordered on buy-ups, toasties from his beloved sandwich maker and his coffees — he likes them black, with lots of sugar — Milat always believed he would be freed on a legal appeal.

If that didn’t work, he was always scheming an escape, usually via a hospital stay after self-harming by swallowing metal or, in his most famous attempt, by cutting off his finger.

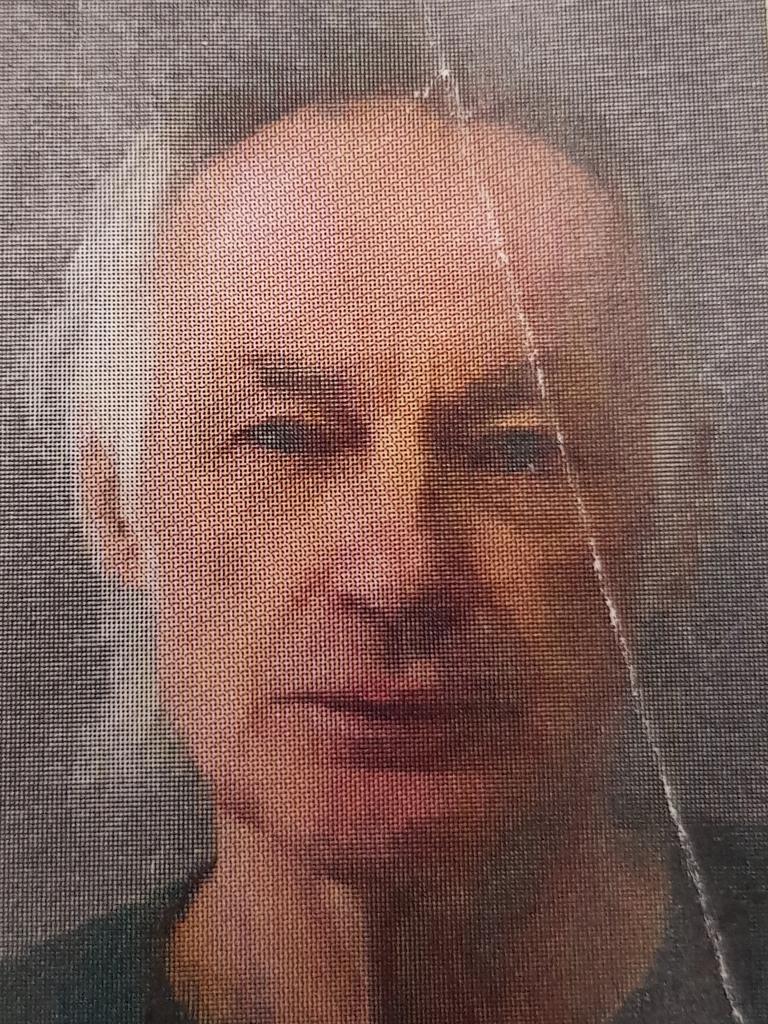

When news.com.au last saw Milat in Supermax, about a decade ago, he had a weird red mark blighting his brow.

Prison officers said Milat continually “bussed” his head against the prison wall to produce a rash or wound and a possibility of an external visit to hospital.

When Milat wrote a personal letter to news.com.au from Supermax he said his day-to-day existence was quite comfortable, the food was OK and his cell with extra rooms was a bit like an apartment.

Milat, who died aged 74 as a result of oesophageal and stomach cancer while being treated at Long Bay jail's hospital wing, said conditions inside Supermax were much better than other prisons he’d been in.

He could wander about during the hours outside his cell.

Referring to himself as “one” and using quaintly elaborate prose, Milat told news.com.au: “It’s not that we (are) just stuck in a cell all day. I have the front and back as well.

“During the day one can wander around the front or back yard,” Milat wrote in neatly penned handwriting.

“Of course, alternatively, one can elect to go to other areas, library etc, exercise yards, basketball court, the oval walk-running track.”

Milat also said he had hot and cold running water, power points and access to a phone in his Supermax unit (but not his cell) when he wanted to use it.

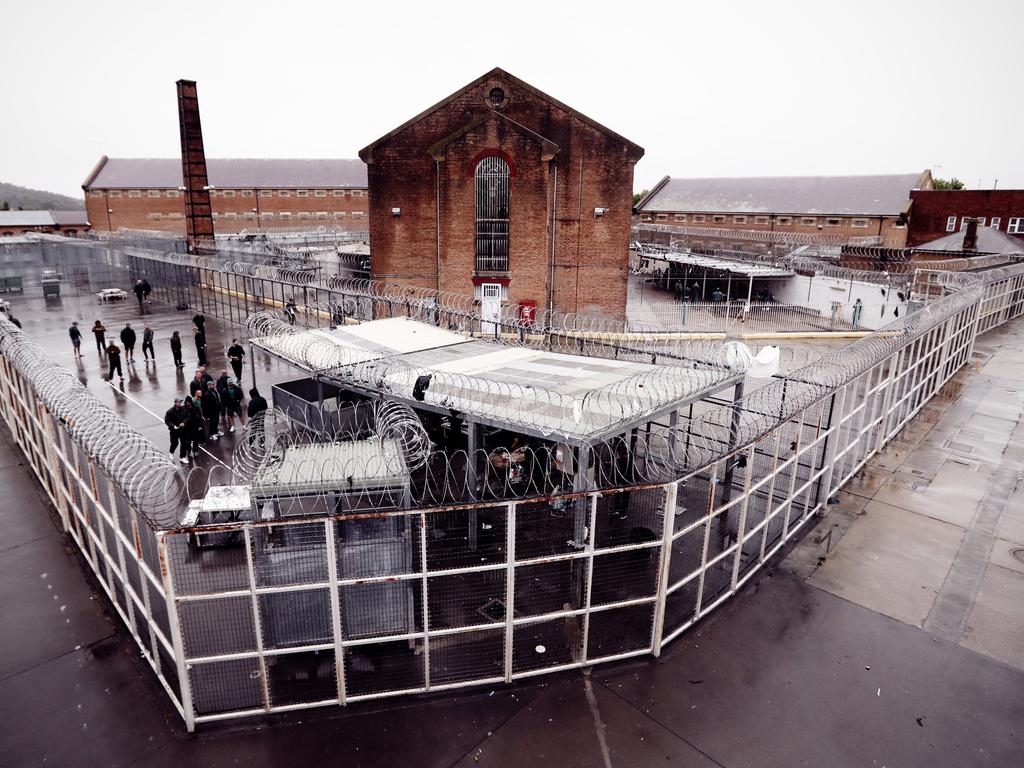

Supermax, or the High Risk Management Correctional Centre, is a jail on its own within the Goulburn prison complex on the NSW Southern Tablelands

Supermax, Milat’s home since September 2001 before being transferred to Long Bay, lies just an hour’s drive down the Hume Highway from the Belanglo Forest where he tortured, murdered and buried the seven backpacker victims he picked up on that road.

Milat was transferred to the Aged and Frail Unit for criminals inside Long Bay prison complex in southern Sydney as a result of his cancer cancer.

That unit has been home to gangster Arthur Stanley “Neddy” Smith for years and was where Anita Cobby killer Michael Murphy lived before his death from cancer in February.

Neither Smith nor Murphy were housed in Supermax, both killers presenting little threat to their jailers, despite a ludicrous report in 2017 Smith tried to escape from Prince of Wales hospital’s secure wing.

Smith — who has advanced Parkinson’s disease and some dementia — has used a walking frame behind bars for at least a decade.

But wiry and wily Milat has always posed a risk to prison bosses.

Milat’s Supermax prison file was marked “highly manipulative inmate” with a “high risk of self harm via hunger strike if things don’t go his way”.

And with each of Milat’s multiple attempts at self-harm in his Supermax cell, prison bosses always feared they were attempts to get him out of prison and into hospital, where he had a better chance of escaping.

Milat’s hunger strikes to the same end never lasted long because he “loved his tucker” too much.

But as his letters show, he may have been a psychopath and a merciless killer, but he was intelligent and always thinking.

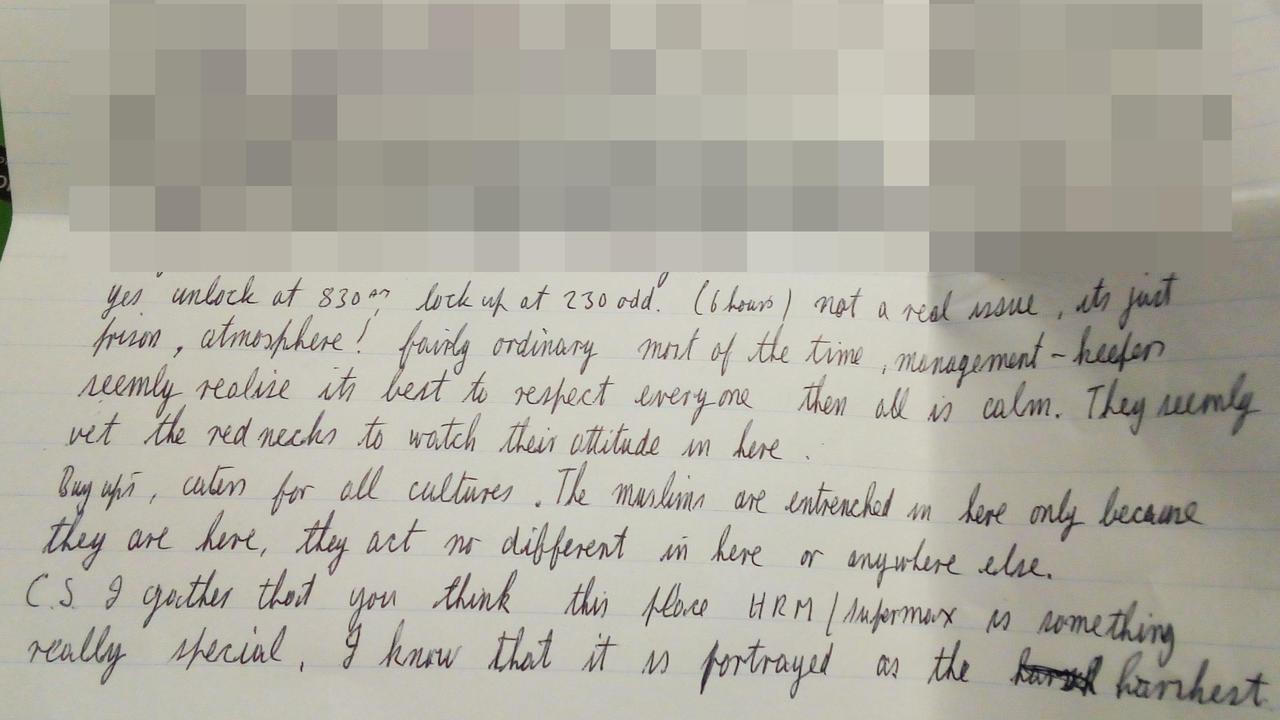

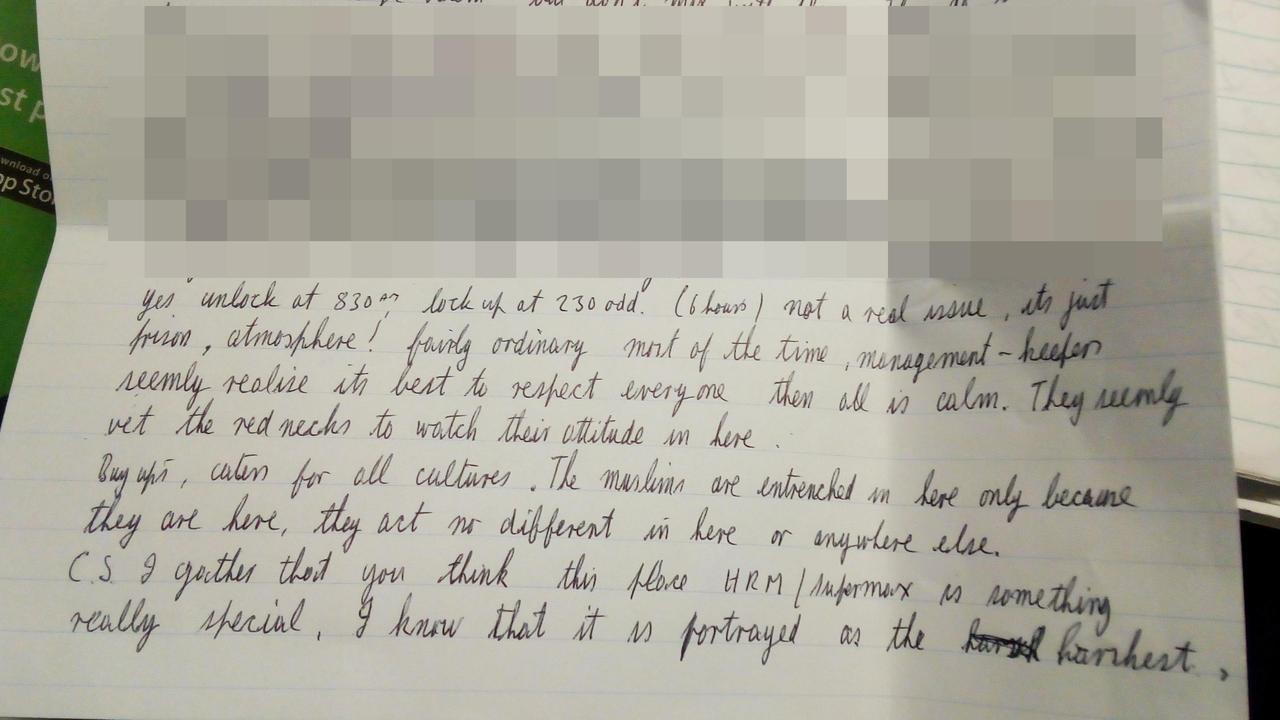

“I gather you think this place HRM/Supermax is something really special,” Milat writes.

“I know that it is portrayed as the harshest place in the system.

“I know that for (now retired) Commissioner Woodham’s tenure he certainly made out that it was a cross between a Russian gulag and Auschwitz.

“It certainly is high security, the number of keepers to care for us, five-six or more before they open up a cell even just to hand over the mail or our meals.

“It’s not a concern for me or anyone, it’s just how it is. I can see how it costs $320,000 a year per HRMU prisoner.”

Milat was 57 years old when he was moved into Supermax, three months after it had opened to house inmates who were violent, terrorists, or escape risks

The serial killer had been convicted in 1996 and handed seven life sentences for the murders of two Australian, two British and three German backpackers aged in their 20s.

In 1997, at (the since closed) Maitland jail, Milat hatched a brazen but doomed escape plan with drug baron George Savvas to escape.

Savvas had previously escaped from Goulburn jail by walking out of the visitors’ room wearing a blonde wig and fleeing to South America.

Milat and Savvas’s plan was to take guards in the reception area hostage, but their plans were leaked to authorities.

The next day Savvas was found dead in his cell, and Milat was transferred to a secure unit at Goulburn prison complex.

The following year he was taken under heavy guard, handcuffed and shackled, back to Maitland for the inquest on Savvas’s death.

In 1998, Milat also lost his appeal to the NSW Court of Appeal and launched an appeal to the High Court in Canberra, calling for his case to be the subject of a judicial review.

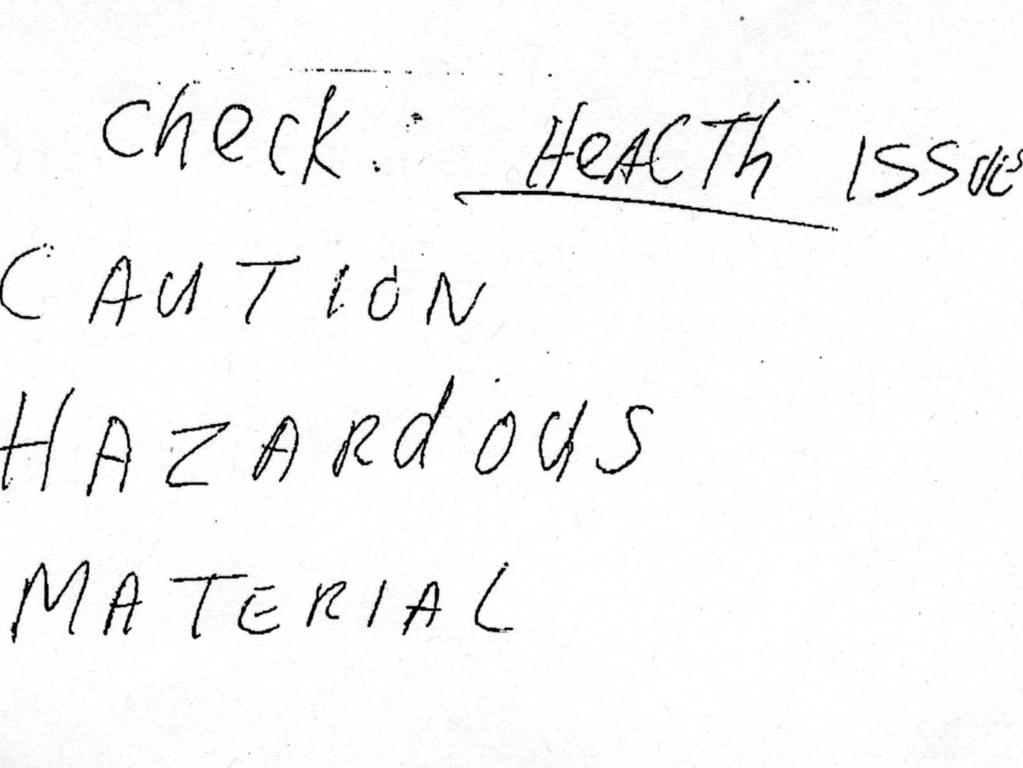

In early January 1999, prison officers using a metal detector found a 10cm hacksaw blade in a packet of biscuits in his cell.

He was immediately segregated in another cell.

Months later, writing to his old cellmate Makkah, with whom he had been locked up after his original May, 1994 arrest, Milat complained he was still in virtual solitary confinement.

In the letter, of which news.com.au has a copy, Milat writes about doing legal study on his case and his hopes of new DNA tests on evidence from his victims.

“Still in segro-solitary conditions,” he wrote, “no chance of it changing unless I take real drastic steps.

“But at least at this point I get an hour a week with the legal tutor.

“Anyway thanks again — I am very aware of DNA but under the impression that it all gone.

“They would refuse an independent report.”

Milat then notes the three murders of women on the Sunshine Coast in two years.

He is probably referring to the disappearances of Jessica Gaudie, Celena Bridge and Sabrina Ann Glassop.

British backpacker Celena Bridge vanished in July 1998, followed by Ms Glassop in May 1999, and 16-year-old schoolgirl Jessica Gaudie three months later.

Farm worker and Aboriginal tracker Derek Sam was later sentenced for Ms Gaudie’s murder, but police have been investigating whether Sam killed all three.

“I have my own ideas on that and who,” Milat writes about the murders.

In 2000, he staged four hunger strikes and slashed his arms with a sharp instrument in an effort to draw attention to what he alleged was his path to appeal being blocked.

Prison authorities suspended his privilege of using the jail’s law library and confiscated books, letters and documents from his cell.

On February 22, 2001, Milat swallowed three razor blades, 24 paper staples and a tiny metal chain in protest against his continued solitary confinement.

He was serving the longest spell in solitary given to a prisoner in NSW since the last century.

He was rushed to the clinic inside Goulburn maximum security jail where the metal objects were detected on X-ray.

In a letter to a friend on the outside, Milat wrote: “Today I swallowed a quanity (sic) of old pieces of razor blades, a heap of staples (24 I believe), some other bits and pieces of iron work.

“This act, like previous past acts, are solely done to highlight the problems I face in attempting to get my appeal going.

“It is not a suicidal thing.’’

After the incident, Milat’s brother Wally told The Sun-Herald he was seriously concerned about Ivan’s health.

“The prisons department is determined to make things difficult for him,’’ Wally said.

He said family letters sent to the prisoner often took weeks to arrive, and Milat’s letters to his sisters and brothers were subject to long delays.

Another brother, Bill Milat, said: “Ivan will continue to do these things until his appeal is heard.

“All kinds of obstacles are being placed in his way.

“It’s his only course of action … but being Milats, nobody is going to take any notice of us.’’

After the razor blade incident, Milat wrote, “After three years and eight months in this solitary-segregation I don’t care how long they keep me like it.

“But I do expect basic services available to others to be given to me.”

Supermax jail opened in June 2001, a 75-bed facility billed by the state prison system’s then boss Ron Woodham as his toughest jail and virtually “escape proof”.

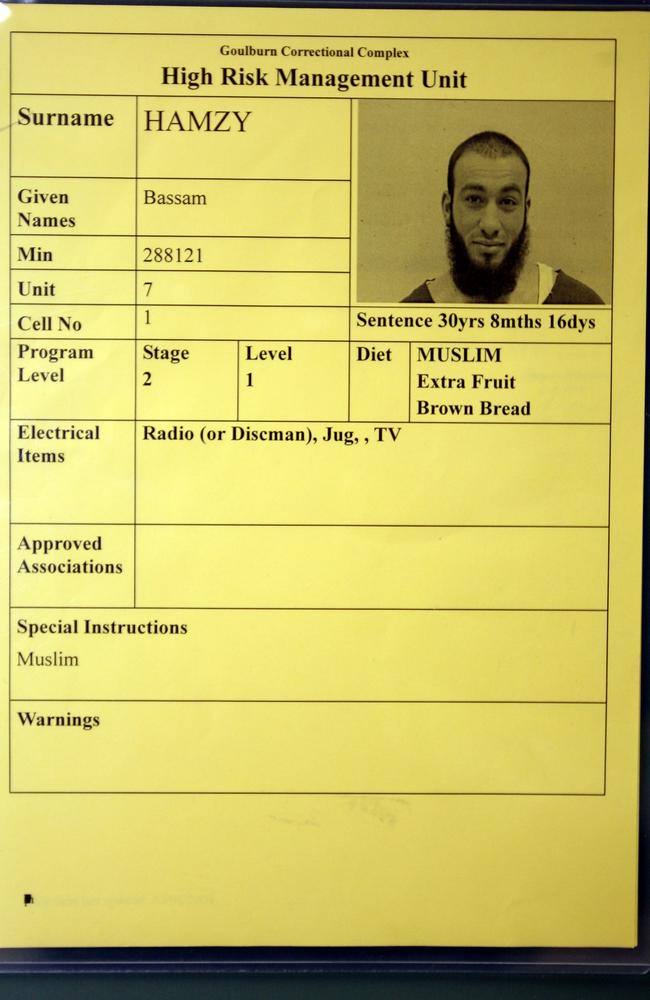

By September, Mr Woodham had moved in 15 “guests” including Milat, multiple murderers Lindsey Rose and Malcolm Baker, gang rapist Bilal Skaf and killers Guy Staines (who has since died fighting in Syria) and Emad Sleiman.

Mr Woodham said the men, known as escape risks for their violent or disruptive behaviour in jail or for bashing other inmates or prisoners, would all be housed in single cells.

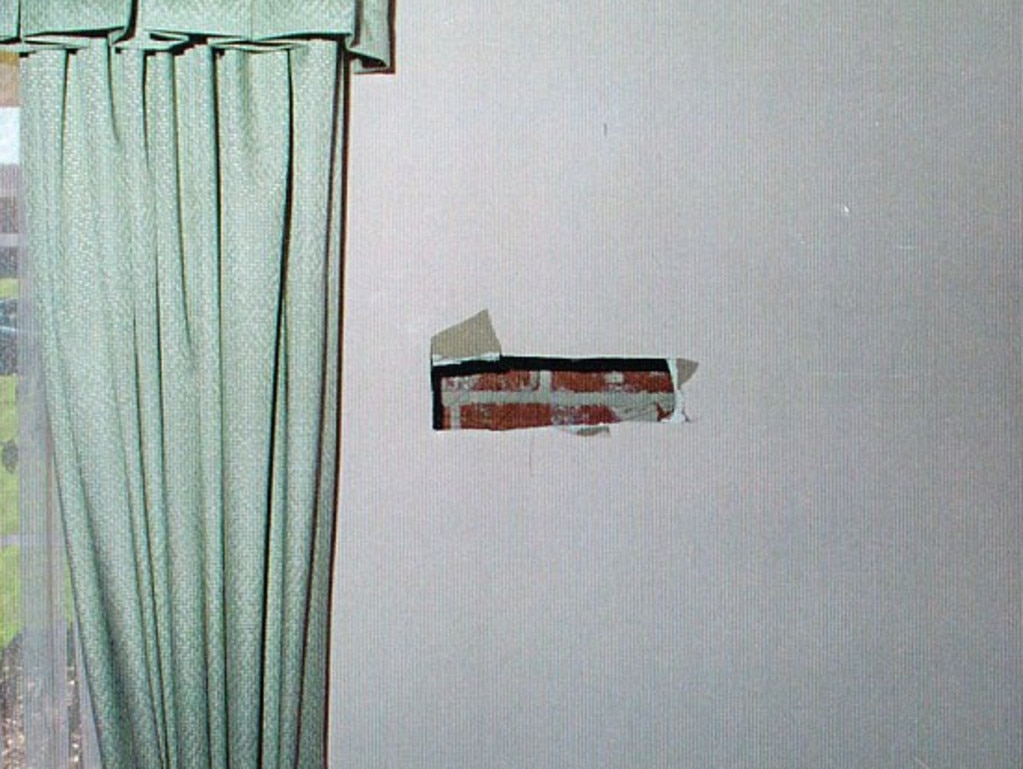

Each two-metre by three-metre cell had a cement base bed with a foam mattress shelf, toilet, shower and basin, and an attached steel cage where prisoners could breathe fresh air.

Each cell had access to a day room.

A small exercise yard with running track and two half-size basketball courts lay outside, but access to them would be a privilege earned by good behaviour.

High-powered rifles were trained on the yard, a camera rotated overhead 12m up in the sky and wires crisscrossed the air above the courts to deter aerial approaches.

“Ivan has already said he’s got no worries about coming in here,’’ Mr Woodham said.

Milat would earn privileges by good behaviour.

He was offered access to the Supermax basketball court and running track, but the once fit Milat declined, saying he was no longer fond of exercise.

Instead, he spent most of his day in his cell, occasionally taking visits from friends and family.

In April 2003, Milat sparked a security scare when he deliberately slammed his hand in a door.

He required 24 stitches to fingers on his left hand, telling officers he was protesting at not being given enough time to use the prison computer to work on his appeal.

However, prison bosses believe it was an attempt by Milat to be moved to an off-site hospital from which he could escape.

Milat continued to write letters, keeping in regular contact with one in particular of his brother's wives who believed strongly in his innocence.

In a letter she writes about family things, home renovations, holidays, and reveals one of his nieces wants to write a book about him.

She also writes his brother Richard had spoken to Channel 9, one of various relatives who have worked with TV producers, often for a fee, in shows about Milat’s dark deeds.

In 2004, police continued to investigate other murders that could have been done by Milat, and media coverage sparked Milat to write to then NSW premier Bob Carr.

Milat accused him of “discrediting me in the minds of the public” and marring his chance of appeal.

He wrote Mr Carr’s government had “succeeded in having me viewed … by much of the public as not being part of society at all”.

Talking about himself in the third person, the serial killer said “Ivan Milat” was the subject of a conspiracy and “the vilification of Ivan Milat” continued with other murders levelled at him.

On June 21, 2006, The Daily Telegraph revealed Milat had a television and sandwich maker in his cell.

The items were inmates privileges, a reward for not engaging in acts of disobedience or self-harm.

The storm of protest that ensued about the serial killer’s prison perks became known within corrections as the “Ivan Milat sandwich maker controversy”.

Premier Morris Iemma stepped in to remove both items, and Milat promptly went on a hunger strike.

Mr Woodham reported the killer had said to him, “You’d better put me in a safe cell”, which Mr Woodham interpreted as meaning “he was going to attempt to harm himself”.

“He does threaten suicide from time to time,” Mr Woodham said.

“Some of it is to get sympathy, but it’s a fine line between an attempt and a successful suicide.”

The removal of the toaster maker and TV sparked a letter from Milat’s elder brother Boris (a self-described Milat clan outcast).

Boris described his brother as a “sick and twisted human being” but someone who deserved not to be kept “isolated … in a cage” but treated by “counsellors and psychiatrists”.

“I am already a Judas to all my brothers and sisters for taking what I consider a civilised stand by not supporting the denial of his actions, as I see him guilty as convicted,” Boris wrote.

“He has been removed from society, and that’s where the punishment should stop.

“I have yet to see any jail that in anyway represents a ‘holiday’.”

Milat was on suicide watch for four days before returning to his Supermax cell and normal jail meals.

By July 15, 2006, Milat had his sandwich maker and TV back.

Mr Woodham said when Milat was watching TV, he wasn’t bothering the prison officers.

“The people that complain about him having a TV, I’d just like them to give some thought to my staff,” he said.

“They have to go with these psychopaths and manage them every day.”

One afternoon at Supermax when Mr Woodham and the senior police officer who tracked down the serial killer, Clive Small, were visiting inmates, news.com.au went along.

Inside Unit Nine, killers and rapists stared through the glass of their day rooms as Mr Woodham and Mr Small and the late ICAC commissioner Jerrold Cripps moved around.

When we got to Milat’s day room, the serial killer began to become agitated.

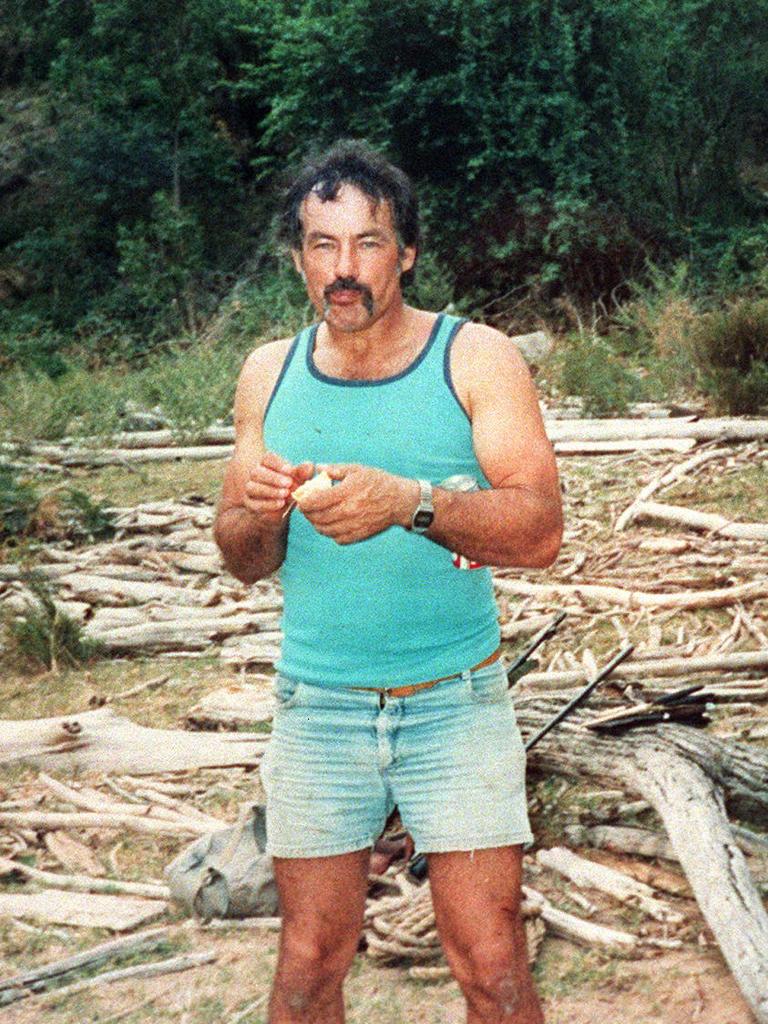

Looking old and paunchy, his belly extending over the elastic waistband of his prison green tracksuit pants, his hair long and grey, Milat stared at Mr Small.

Not sure exactly who he was for a few minutes, it would dawn on him this was the detective who basically locked him up.

Milat began talking quickly and punching the air, arguing a point about one of the young backpackers he shot or stabbed to death in Belanglo.

Inside Supermax at the time, Milat was one of 34 men who had committed 45 murders and are serving combined sentences of about 500 years.

The day turned out to be one on which Milat almost confessed to his crimes.

The tour group passed through two sets of locked doors, down a driveway through high fences topped with razor wire and into the clinical and creepy confines of the HRM.

Milat’s forehead was streaked red from bussing on the wall.

No other inmate had deigned to speak with the instantly recognisable form of commissioner Woodham, but Milat did.

He complained about Supermax, wanted more time in the yard and kept glancing back at Mr Small.

Gesticulating and talking about evidence, he said, “The DNA in the hair. Nothing to do with me.”

Milat was talking about strands of hair found in one of his victims, British backpacker Joanne Walters’ hand when her body was found in 1992.

Conventional DNA testing done by police proved the hair samples did not belong to Ms Walters or Milat, and the remaining uncontaminated strands were quarantined as evidence pending an advance in science to test them.

Mr Small fixed his gaze on Milat and told him the DNA evidence of the hair did not prove he was not guilty.

Milat did a double take.

“I know you,” he said.

Mr Small introduced himself, and a wave of something passed through Milat.

Milat began babbling about his late sister, Shirley Soire, who Mr Small’s investigative team had cleared of any connection with the murders.

But Milat’s lawyer John Marsden had, before his own death, said he suspected Ms Soire was involved.

“You said she was connected,” Milat fumed to Mr Small, “she wasn’t, she …”

Mr Small smiled. “No, Ivan,” he said. “I’ve always said you acted alone.”

“Yes, so why are you …,” Milat trailed off, staring at Mr Small and then retreating to his cell.

Not quite a confession.

On the afternoon of January 27, 2009, while sitting in his cell, Milat cut off the little finger of his left hand with a plastic knife and placed it in an envelope he had addressed to the High Court of Australia.

Her handed the envelope to a prison officer around 3.30pm.

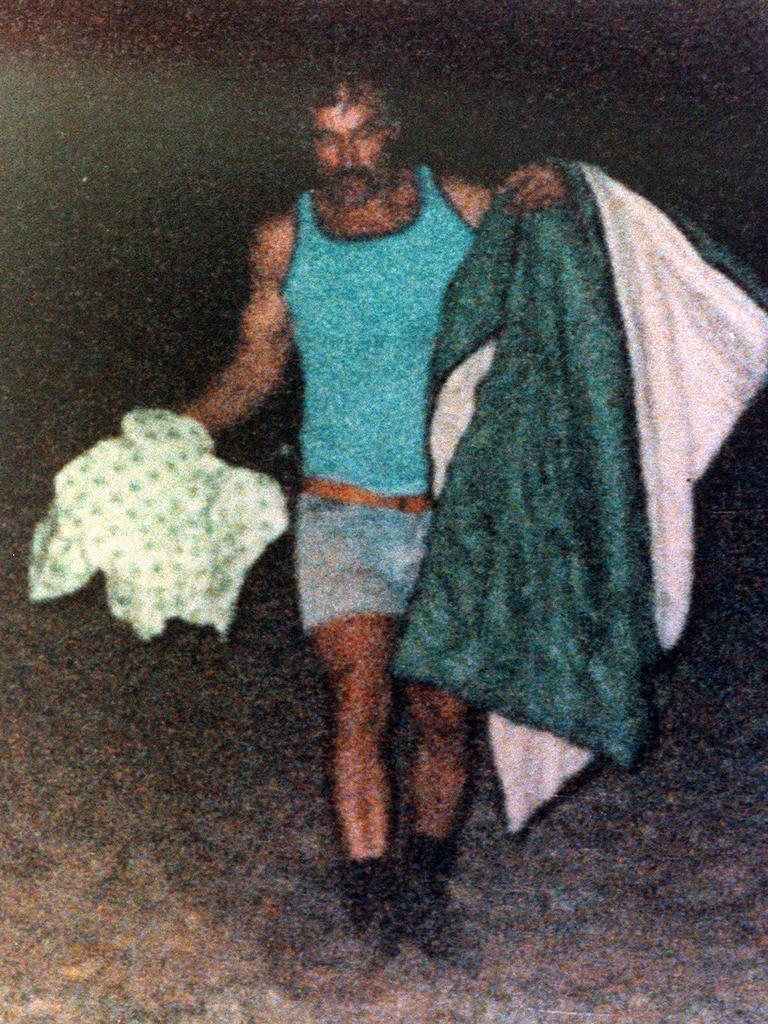

Four high-risk escort officers accompanied Milat, handcuffed and shackled in an orange jumpsuit, to Goulburn Base Hospital where surgeons were unable to reattach the finger.

Mr Woodham said at the time of Milat, “He is very close to losing his marbles.”

Milat later admitted in a letter to his brother Bill, it was “ridiculous” he had cut off the finger to get attention but, “I don’t regret it, though it was a stupid act.”

In 2016, I wrote to Milat and received a letter in reply in which he talked about his life in Supermax, the sandwich maker controversy and the prison’s mostly Muslim inmates.

He revealed how he had schemed to get his Breville sandwich maker back all because a few “aged pensioner” groups were upset by the supposed luxury.

“I recall that particular morning,” Milat wrote. “The headline news was how aged pensioner and victim groups was upset that I had a Breville sandwich maker and a TV set in my prison cell.

“Breakfast TV news certainly played it up and the Minister for Corrective Services now was ordering the Commissioner to remove those items from me.

“And of course the boofhead manager of HRMU carried out that task. I protest which annoyed boofhead so I thrust into the safe cell because of my attitude.

“Safe cell (a pseudo word for punishment) … in olden times called the ‘Black Peter’, no lights — utter darkness … now this safe cell is a cement box devoid of fittings and the lights left on continually whilst the prisoner is there.

“There is no openings once door shut, no windows, no contact, cannot hear anyone, very silent, deprived of any sense of time, a punishment place.”

But Supermax generally was an easier place to do time than out in the yards of Goulburn main prison.

Milat told news.com.au Supermax inmates at “HRM” received privileges “to keep us calm”.

“HRM they supply all our gear, TV radio etc, out in main prison one has to purchase all of it,” he wrote.

“HRM seemly they supply it to keep us calm. If it breaks down, they replace it.

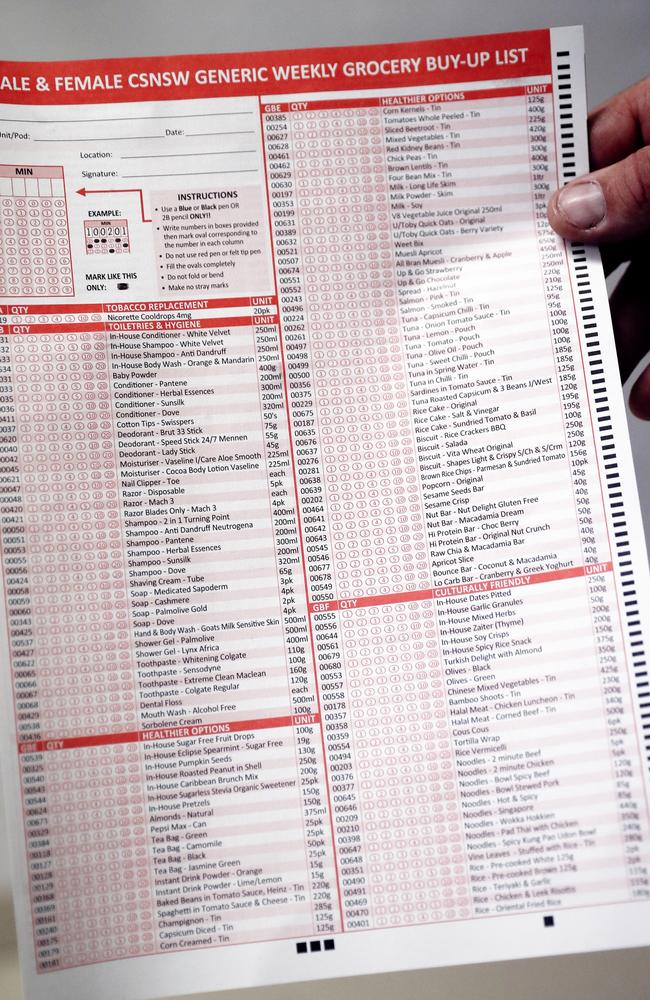

“The food is fairly good. In 2001 it came to us in sealed packs and that is how it is in all NSW prisons.

“Any special diets, Muslims etc. are catered for. No guess work on that, once a person declares himself a Muslim then he always issued the religious friendly meals.”

Milat, who is one of only two non-Muslim prisoners in Supermax, said he spent the time mostly to himself and conditions were not harsh as portrayed in the media.

“It’s not a luxury place for sure, it’s a prison, but compare the main prison, their conditions with this place.”

Milat also revealed the atmosphere in Supermax was fairly calm because prison officers realised they had to keep the violent murderers on an even keel.

“Fairly ordinary most of the time,” he said, “management-keepers seemly realise it’s best to respect everyone then all is calm.

“They seemly vet the rednecks to watch their attitude in here.

“In reality in this unit, I’m the only odd one out, as they all associate with each other. Unlock at 8.30am, lock up at 2.30 odd (6 hours) not a real issue, it’s just prison, atmosphere.”

Asked how he was affected by the overcrowded prison system, as it is often portrayed by Corrective Services NSW, Milat said crowding wasn’t an issue in Supermax.

“You refer to crowded in HRM?,” he writes, “it isn’t.

“I am aware of overcrowding in the prison system generally, mattresses on floor to accommodate prisoners!

“So if I’m in a group of 3 cells … they open up to a front common room and at the back a back yard so to speak.

“It’s not that we (are) just stuck in a cell all day. I have the front and back as well.

“Front room, table, chair, fridge, sink, hot/cold taps, bench, power points etc, and a similar space area at the back.

“If one wishes a phone call you tell the keepers and they take you to the phone.”