Why politics needs more bullshit and less honesty

THE world is built on a lie, and Australia is no different. The truth is, if you take away the crap, the whole thing collapses.

WE ARE often told that we need more honesty in politics, more people power, that our leaders need to speak the truth.

But the real truth is that we can’t handle the truth. The real truth is that the world is built on bullshit. Take away the bullshit and the world collapses.

This is true at every level of society. If everyone was completely honest with their partner — voiced every nagging criticism or every sexual fantasy — not a single relationship would survive. If every parent was completely honest with their children no child would ever eat their vegetables or have their bath or go to bed feeling safe and secure. If every worker was completely honest with their colleagues no workplace would function. Just look at what happens every time private office emails are publicly exposed: almost invariably someone gets fired and the company dragged into disrepute.

And now, due to a combination of public outrage and cynical partisanship, our political leaders have been forced to be completely honest about who they are and where they have come from — even when they themselves have no idea.

And, needless to say, the result has been nothing short of catastrophic.

A few months ago it would have been nigh on impossible to imagine Australian government getting more dysfunctional and chaotic than it has already been over the past decade and yet this current generation of parliamentarians has somehow managed to achieve it.

At first it seemed harmless enough. A couple of Greens senators had apparently forgotten they were born overseas and, like most misfortunes to befall the Greens, it was pretty funny.

Now it is likely to bring down the government, which might also be funny too if it didn’t keep happening so often.

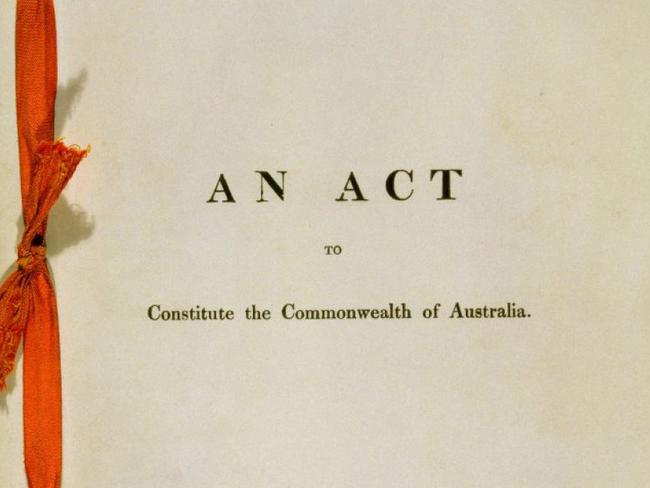

At issue, as everyone now knows, is the once relatively obscure Section 44 of the Australian constitution, which sets out what disqualifies a person from becoming a member of parliament. This includes, among other things, “any person who is under any acknowledgment of allegiance, obedience, or adherence to a foreign power, or is a subject or a citizen or entitled to the rights or privileges of a subject or citizen of a foreign power”.

The intent of this part of the section seems pretty obvious: You can’t be an Australian parliamentarian if you are not an Australian citizen.

There is only one catch: When the constitution was written there was no such thing as an Australian citizen.

In fact every so-called “Australian” — with the telling exception of those who had arrived some 60,000 years earlier — was assumed simply to be a British subject.

Even in 1906, a good five years after Federation, the same High Court declared: “We are not disposed to give any countenance to the novel doctrine that there is an Australian nationality as distinguished from a British nationality.” That concept didn’t exist in law until 1949, almost half a century later.

And so the constitution as framed assumes Australians are British citizens and when it warns against allegiance to “a foreign power” it means a power foreign to Britain.

And yet now we have a crisis in which the majority of those booted from parliament have been exiled because they were British citizens, even though they themselves didn’t know it and the constitution always assumed they were it.

Confused? You should be, because the whole thing makes no sense. As a result this part of Section 44 has been almost entirely ignored until now.

Indeed, the only time it came into play in recent history was in passing. This was during a case 25 years ago in which it was claimed that the newly elected independent MP Phil Cleary was ineligible to take Bob Hawke’s old seat of Wills because he had held an “office of profit under the Crown”.

This is another part of Section 44 whose meaning seems clear: If you are a financial beneficiary of the government there is an obvious conflict of interest in you seeking to become an MP of said government or in opposition to it.

Or if you are a public servant — who is supposed to be impartial — you cannot be an MP whose role is inherently political.

Phil, as it happens, was a schoolteacher on unpaid leave. Even so, the High Court found that he was still technically an “officer” of the Crown and so was ruled ineligible.

As it happened Cleary won at the next election anyway but what was more interesting was what the High Court said about his competition. Two of them, it turned out, were dual citizens who had failed to renounce their foreign citizenship.

Even though the court didn’t have to, it chose to explicitly state that they too were ineligible to sit under the other provisions of Section 44.

This should have put a rocket under the arse of every serious political party in Australia and indeed for the Labor Party — whose candidate was one of the two pre-emptively disqualified, and which had thought the seat was theirs — it did.

At its best the ALP is both a brutal and beautiful political machine. It puts its members through so much shit before they even become candidates, let alone get elected, that all the skeletons have been dug up and reburied even deeper.

It is telling that no Labor MP has yet been forced to resign because of the citizenship scandal and the only ones under a cloud are there because despite acting to renounce their dual citizenship before being elected, the confirmation of that renunciation may not have occurred until after the election date.

This is why the party has been so insufferably smug and brutally effective in belting the government on the issue.

Or at least it was.

The key thing about the Cleary case of 1992 is that the High Court referred to candidates needing to take “reasonable steps” to renounce foreign citizenship. It is clear from the misguided confidence of the government that it expected — no doubt on advice from the Solicitor-General — that the High Court would consider it “unreasonable” for a candidate to take “reasonable steps” to renounce a citizenship they didn’t know they had.

Or perhaps couldn’t “reasonably” be expected to know — such as one conferred retrospectively or by parentage, as opposed to that of an MP who knew they had been born overseas but hadn’t bothered to check the paperwork.

But the High Court’s bombshell decision last month was anything but reasonable — even though it mentioned the word “reasonable” no less than 23 times, including a whole section devoted to the meaning of “Reasonable Steps”.

The court even ruminates on what knowing something actually means, in a passage that is both incredibly Zen and incredibly strict, a bit like the cops busting in on a bong session in the middle of Pink Floyd’s Comfortably Numb:

“In this regard, the state of a person’s knowledge can be conceived of as a spectrum that ranges from the faintest inkling through to other states of mind such as suspicion, reasonable belief and moral certainty to absolute certainty. If one seeks to determine the point on this spectrum at which knowledge is sufficient for the purposes of ss 44(i) and 45(i), one finds that those provisions offer no guidance in fixing this point. That is hardly surprising given that these provisions do not mention the knowledge of a person or the person’s ability to obtain knowledge as a criterion of their operation.”

No, Sections 44 and 45 of the constitution certainly do not offer any such guidance. Some might say that’s the High Court’s job. That’s why Denis Denuto once famously said: “It’s the vibe of the thing, Your Honour.”

But the High Court has now found there is no vibe. This is what it states under the heading “Reasonable steps”:

“Section 44(i) is not concerned with whether the candidate has been negligent in failing to comply with its requirements. Section 44(i) does not disqualify only those who have not made reasonable efforts to conform to its requirements. Section 44(i) is cast in peremptory terms. Where the personal circumstances of a would-be candidate give rise to disqualification under s 44(i), the reasonableness of steps taken by way of inquiry to ascertain whether those circumstances exist is immaterial to the operation of s 44(I).

“The reasons of the majority in Sykes v Cleary do not support the proposition that a person who is a foreign citizen contravenes the second limb of s 44(i) only if that person actually knows that he or she is a foreign citizen and fails to take reasonable steps available to him or her to divest himself or herself of that status under the foreign law. Nor do the reasons of the majority in Sykes v Cleary support the view that a person who is a foreign citizen is not disqualified if, not knowing of that status, he or she fails to take steps to divest himself or herself of that status.”

In other words it doesn’t matter what steps you’ve taken to find out if you’re a foreign citizen or renounce your foreign citizenship, nor does not knowing you’re a foreign citizen excuse you from not taking steps to renounce your foreign citizenship, which even if you did would not necessarily matter anyway.

It’s hard to know whether it’s a court judgment or a passage from The Hitch-Hiker’s Guide to the Galaxy.

The High Court’s position is thus apparently clear: If you hold a foreign citizenship at the time of your election you’re out.

Except it’s not that clear. It doesn’t explicitly say that — as per the Labor case — if you renounce your foreign citizenship prior to an election but that renunciation is only registered by that foreign power after the election that you are invalid. It only says that you are not necessarily valid.

Confused? You should be. And that is why the Australian government has been running on bullshit and rum fumes and oily rags ever since the first colonists stumbled ashore. Frankly, it’s the only way to manage the place.

This is what makes it so laughingly bizarre that suddenly a whole bunch of politicians are now constitutional zealots.

The Greens, no doubt craving a bit of payback, now appear to be threatening to ask the Governor-General to use his reserve powers dissolve parliament — a concept I’m pretty sure their left-wing ancestors weren’t too fond of in 1975. Indeed, according to official Greens policy the Governor-General shouldn’t even exist.

It is also passing strange that the Greens are now so devoted to the constitution when it was two of its senators being so ignorant of it that created this crisis in the first place.

Indeed, it was not a balltearing media expose, nor a malicious political campaign that sparked the whole government-destroying catastrophe but the abstract curiosity of a layman lawyer from Perth.

Barrister John Cameron told The Weekend Australian in July that he had decided on a whim to check with the New Zealand Department of Internal Affairs to see if Scott Ludlam or Derryn Hinch were still Kiwis.

“I did this as a citizen, not as a lawyer, with a keen interest in the constitution,” he said, expecting that he would catch out the Human Headline and Ludlam would be in the clear. In fact the reverse was true.

The rest, as they say, is history — as the government will soon likely be. And all because someone simply wanted to know the truth.