‘What I did was a horrible thing’: Anu Singh seeks atonement for killing Joe Cinque

ANU Singh laced her boyfriend’s coffee, then watched him die over 36 hours. But when Ginger Gorman tracked her down, she wasn’t expecting this.

IT’S been 18 years since Anu Singh killed Joe Cinque and not a day goes by when she doesn’t think about her crime.

“This is something that I’m going to have to live with for the rest of my life, and I do,” Anu says.

According to Anu, her day-to-day life is plagued with “what happened, and feeling that I need to give back, contribute, make amends, atone. ”

Yet even so, she’s painfully aware of the double bind — that perhaps for her, the debt will never be paid.

“I don’t think you can ever atone for something like that,” she says. Then some minutes later: “What I did was a horrible thing.”

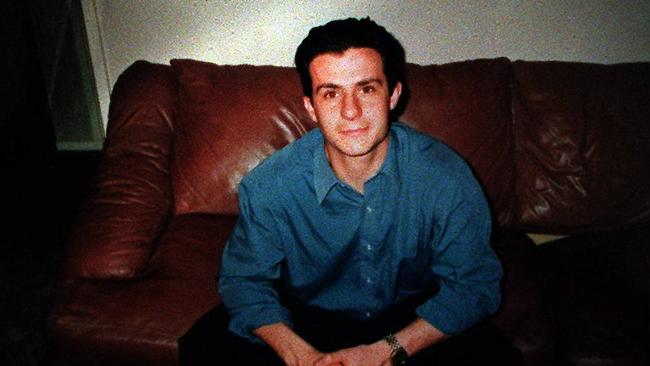

In 1997 Anu was a bright law student at the Australian National University in Canberra. She laced her boyfriend Joe’s coffee with Rohypnol to sedate him and then later injected him with a lethal dose of heroin in their north Canberra flat. It took 36 hours for Joe to die in their bed, while Anu stood by.

After two years on remand, Anu was found guilty of manslaughter, not murder, due to diminished responsibility. This is a defence used when a person is mentally impaired. She served four years of a 10-year sentence and was released at the end of October in 2001. To this day Joe’s parents, Maria and Nino Cinque, believe the justice system let them down.

Anu meets me in a suburban Sydney coffee shop. Despite the scorching weather, we get takeaways and sit outside at a covered picnic table in nearby park; this is not a conversation that a stranger could easily overhear.

I’ve followed this story for more than a decade and there’s never a point at which it starts to make sense.

“I just still don’t understand why Joe died. I don’t understand why you killed Joe,” I say to Anu.

“I don’t understand, either,” she replies. “There’s no rational motivation at all. I was mentally unwell, and I still grapple with that. I still grapple with the whys.

“One of the psychiatrists mentioned a state of disassociation, perhaps, like disassociated from reality. I don’t know. There’s no rational explanation,” Anu says.

“So how do you explain it to yourself?” I ask.

“I can’t. I can’t, and that’s the difficulty,” she says, “I can’t understand where I was at, mentally, for that to happen.”

“What about Joe? You’ve got this chance to study. You’ve got this chance to reinvent yourself, but Joe will never have that chance,” I say.

“I know that,” she replies quietly, then repeats it, as if to show that she really does know.

“If I could turn back that clock. If I could have listened to people back then, and gotten the right sort of help, then this wouldn’t have happened.

“That’s obviously something I live with, and I can’t turn back the clock,” she continues.

Anu explains that once she was incarcerated, doctors put her on the antidepressant drug Zoloft. Within a month the physical symptoms she had been consumed with disappeared.

During her 1999 trial, the court heard Anu believed she was dying from a muscle wasting disease. She felt constantly unwell and complained of not being able to feel her head on her body, aching legs and hot flushes.

She was also bulimic and dangerously thin. Her father, a GP, told Anu she had depression and needed treatment.

“In fact, my mother called a mental health crisis team a number of times, prior to the offence occurring, and I fell through the cracks, as a lot of women do,” Anu tells me.

While we talk, Anu sips her coffee occasionally. She’s nervous and tells me so. Her eyebrows are neatly plucked but underneath the hazel eyes, there are dark circles. Anu’s long, dark hair has lighter streaks and is tied at the base of her neck, just as Helen Garner described in her 2004 book Joe Cinque’s Consolation.

This small detail rings true. Many others do not. Garner described a woman who was manipulative and histrionic.

Today, Anu doesn’t avoid any of my questions. She describes herself as “mentally healthy” and looks me straight in the eye, even when she becomes tearful.

“The fault is mine,” she says, confirming that she “absolutely” takes responsibility for Joe’s death.

Somewhat startlingly, Anu also agrees that she misses Joe — and that she loved him and imagined a future together.

One of the things Anu wishes she could do is talk to Joe’s parents face-to-face.

“Not [to] seek forgiveness or anything like that, just to be able to say, ‘Look, I’m deeply, deeply sorry for all this’.”

While Anu knows that saying sorry is “not going to bring him back, and it’s not going to ease their pain,” she believes “restorative justice can be very healing.”

“I think that me just saying it to you and it being reported ... it means kind of nothing,” she adds.

Anu says she has tried to reach out to the Cinques, but “can totally understand why they don’t want to talk to me and have anything to do with me.”

Maria Cinque graciously agrees to a brief phone conversation with me, despite her own bad health. She’s adamant that Anu will never have the chance to apologise to her in person.

“No way,” Maria says three times in her strong Italian accent, “You tell that. [For Anu] to not come near me.”

“She’s a monster. She’s selfish, she doesn’t think about anybody else. Feel sorry? I don’t believe that. She doesn’t.

“She’s sorry just because of what happened to her, not because of what she did to my son,” Maria says.

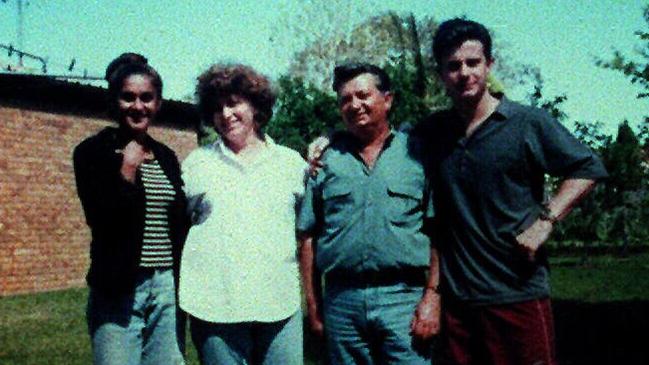

These days Maria often ponders what Joe would be like now, if he were alive.

“He would probably have grey hair like me, and he would be at the top of his job, and he would come to see us and look after us, because we’re getting old,” she says.

Maria also wonders if Joe would have children, like many of his friends.

“After he was gone, it makes everything crumble. His young brother was crushed, too,” she says.

Helen Garner’s acclaimed nonfiction novel is currently being made into a film directed by Canberra filmmaker Sotiris Dounoukos.

Maria is pleased about the upcoming movie and has read the script. She wants her son’s memory to be kept alive.

She tells me of her handsome son’s academic achievements, how he travelled to Europe as a young man and became an engineer.

“I want the people to keep remembering him and what, not just us what we lost, but everybody lost, because he was going to do so many things,” she says.

During our one-hour conversation, it’s clear the film is playing on Anu’s mind. She talks about the prospect of the movie’s release at length, using words like anxious, concerning, confronting, upsetting and stressful.

She’s worried that just like Garner’s book, the movie is going to catapult her back into the spotlight.

“I kind of fear, am I going to be able to walk down the street?

“I’m just trying to get through every single day, because I can’t foresee what’s going to happen,” she says, adding: “It’s going to be tough.”

Anu says she’s concerned how the film will impact both the Cinques and her own family, too.

“They’re completely blameless,” she says.

While Helen Garner was writing her book, she wrote to Anu twice and unsuccessfully requested an interview with her. However Anu claims that the film’s creators haven’t been in touch at all.

“I do fear that because it’s based on Helen’s book, that it won’t adequately explore the mental health aspects,” Anu says.

“It would have been nice if they … talked to me, ” she says, so that they could get “some understanding about where I was at that time.”

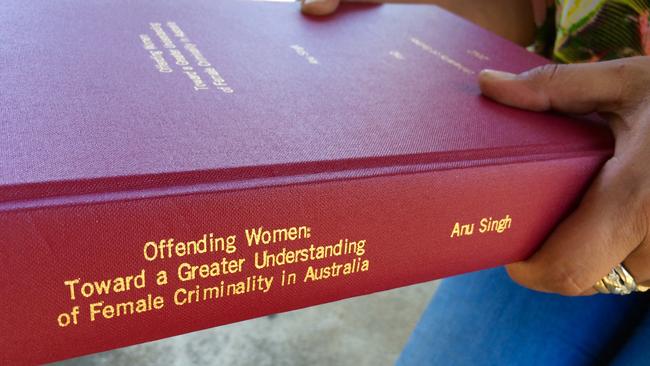

The notion of being a criminal who is “talked to, rather than simply talked about” is one canvassed in the 100,000-word PhD Anu completed in 2012 and more recently published an e-book about.

The research is based on 60 interviews with female prisoners conducted while Anu was incarcerated and a further 15 conducted once she was released.

Her research details the often-harrowing life stories of those women and outlines five major pathways that led the interviewees to crime: unstable upbringings, sexual and physical abuse, drug use, economic marginality and mental illness.

“After doing the interviews, the sense I got was that it’s almost like by continuing to imprison these women, we’re punishing them for society failing to protect them in the first place,” Anu says.

“Some of the stories are just heart wrenching, it kind of puts the crime in context, because crime doesn’t occur in a vacuum.

“Things happen that lead up to this. I mean, in my own case, I was unwell for two years before that happened.”

While Anu does not specifically write about her own crime in the thesis, she does recognise herself in some of the women’s stories, especially those that reference mental health issues.

She sees her ongoing research into the justice system as an attempt to atone and seek redemption.

“I actually felt that because of my unwanted notoriety, maybe people might read this,” she says pointing to the heavy, bound and embossed copy of her PhD lying on the table between us.

However Maria doesn’t believe Anu genuinely wants to atone and help others.

“She wants attention,” Maria says, “Why didn’t she help my son instead? Why didn’t she help him with the ambulance, the police or something. It’s too late now. It’s too late.”

Anu concedes that shifting the spotlight off her may be unlikely in the months to come.

“I know that’s ridiculous in a sense. It’s not going to be completely taken off me, but let’s look at the bigger issues, as well.

“Let’s look at why these women are going to jail at increasing rates, and what we can do to help prevent that,” she says.

Ginger Gorman is an award winning print and radio journalist, and a 2006 World Press Institute Fellow. Follow her on twitter: @GingerGorman