Twist in murder case over Jack the Ripper’s victims

For more than 100 years the world has been captivated by the case of Jack the Ripper. But a new twist sheds light on his victims.

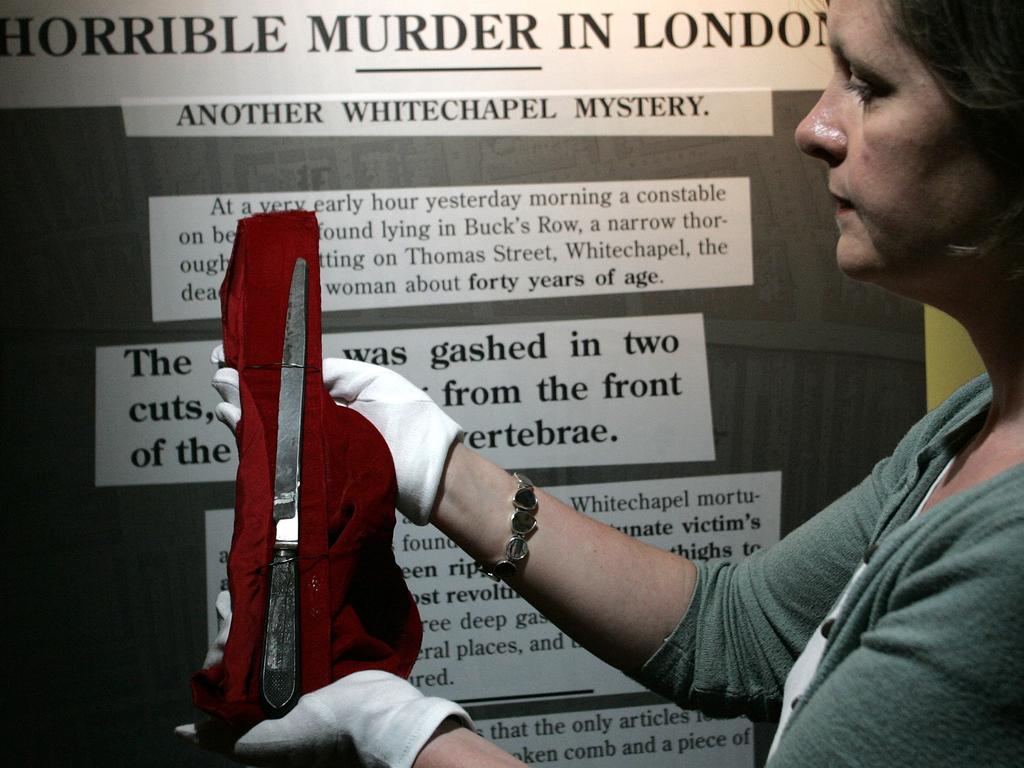

Over two months in 1888, London’s east end was gripped by fear as five women were brutally murdered and mutilated.

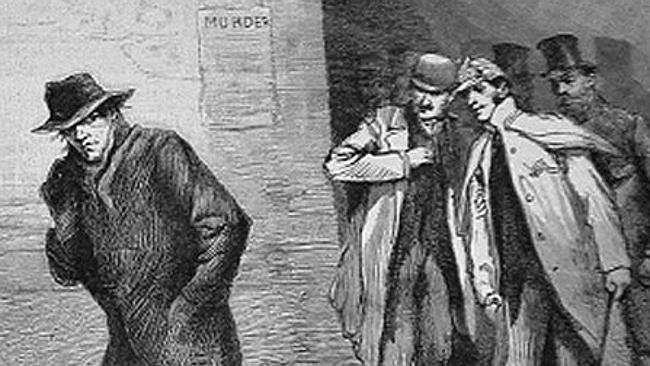

The killings were attributed to a man by the moniker of Jack the Ripper, who remains one of the world’s most infamous — and mysterious — killers.

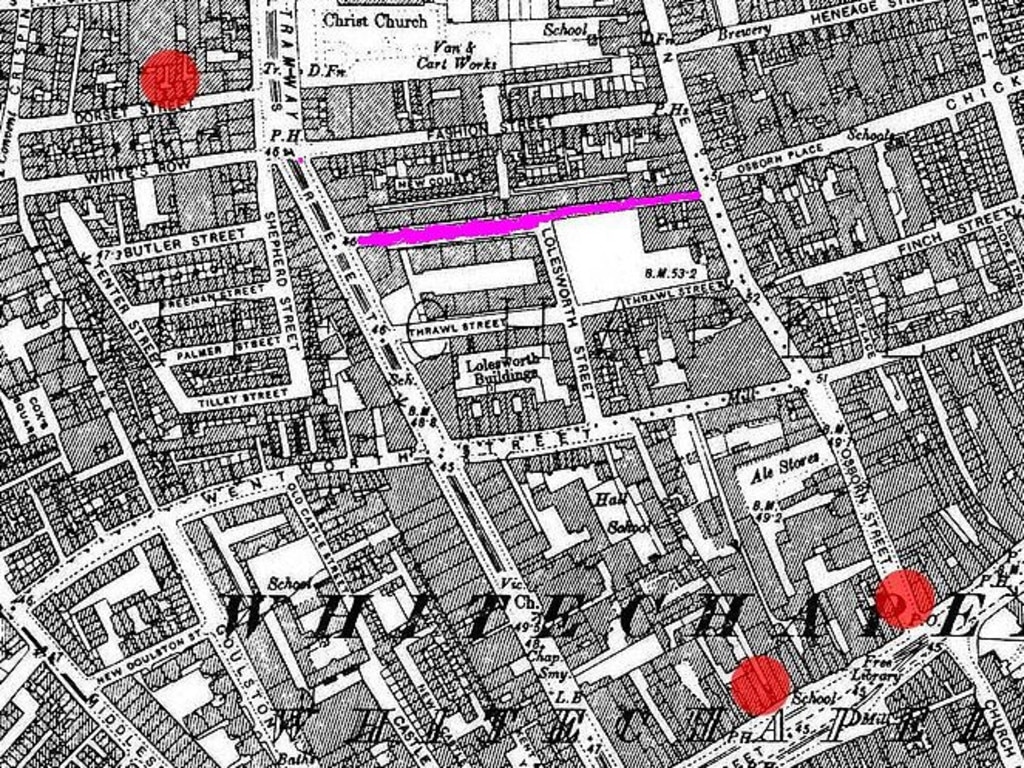

All five killings took place less than two kilometres of each other, in or around London’s Whitechapel district.

The five women murdered by Jack the Ripper were Mary Ann “Polly” Nichols, Annie Chapman, Elizabeth Stride, Catherine Eddowes and Mary Jane Kelly. Each woman had her throat cut, and four of them had their entrails removed.

RELATED: Medical problems: Terror of 19th century operating table

RELATED: Syphilis: Shocking photos of victims before penicillin

RELATED: Wild life of 17th Century sword fighting bisexual

The killings began 130 years ago this month and while debate still continues over the possible identity of the Ripper, little has been written about the women he killed — apart from the widespread assumption that they were all prostitutes.

But that assumption has now been disproved by an author who was determined to learn more about the women than the horrific way they died. To many people, the Ripper’s five victims were nothing more than mutilated corpses.

It’s time to look at these women in a new light and put the spotlight on them, instead of their infamous killer.

The killing spree

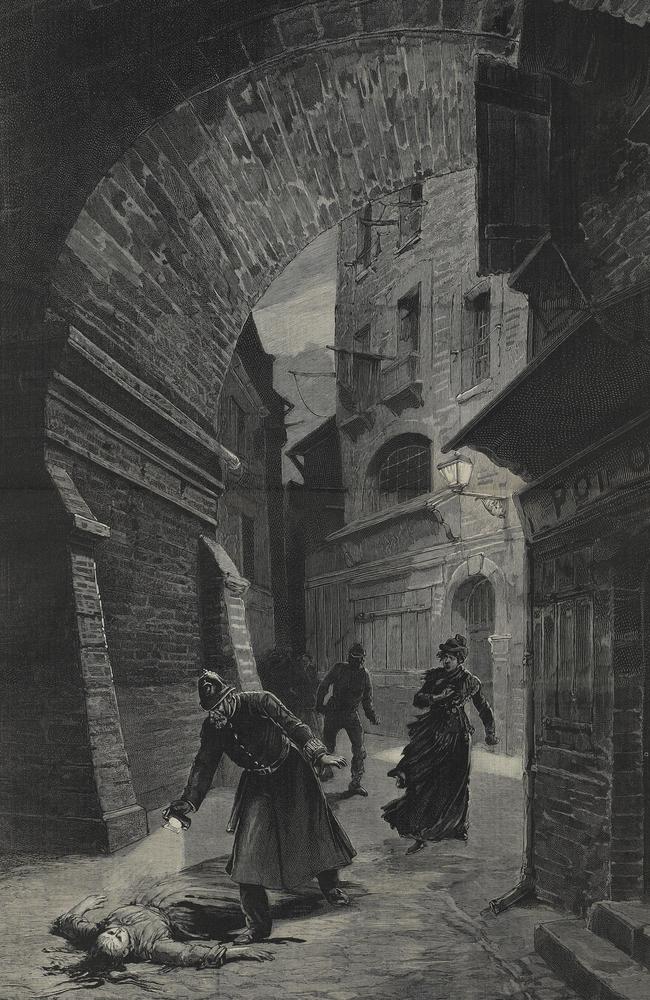

London’s east end in the 1800s was a place to be avoided unless you had the bad misfortune to live there. It was notorious for filth, violence and crime. Prostitution was rife, with thousands of brothels and cheap housing providing sex services. Sex work was only illegal if it caused a public disturbance.

Jack the Ripper’s killing spree began in August 1888 with the discovery of the body of Mary Ann “Polly” Nichols. Her face was bruised and her throat had been deeply slashed and almost severed. Her stomach had been slashed open and she’d been stabbed multiple times.

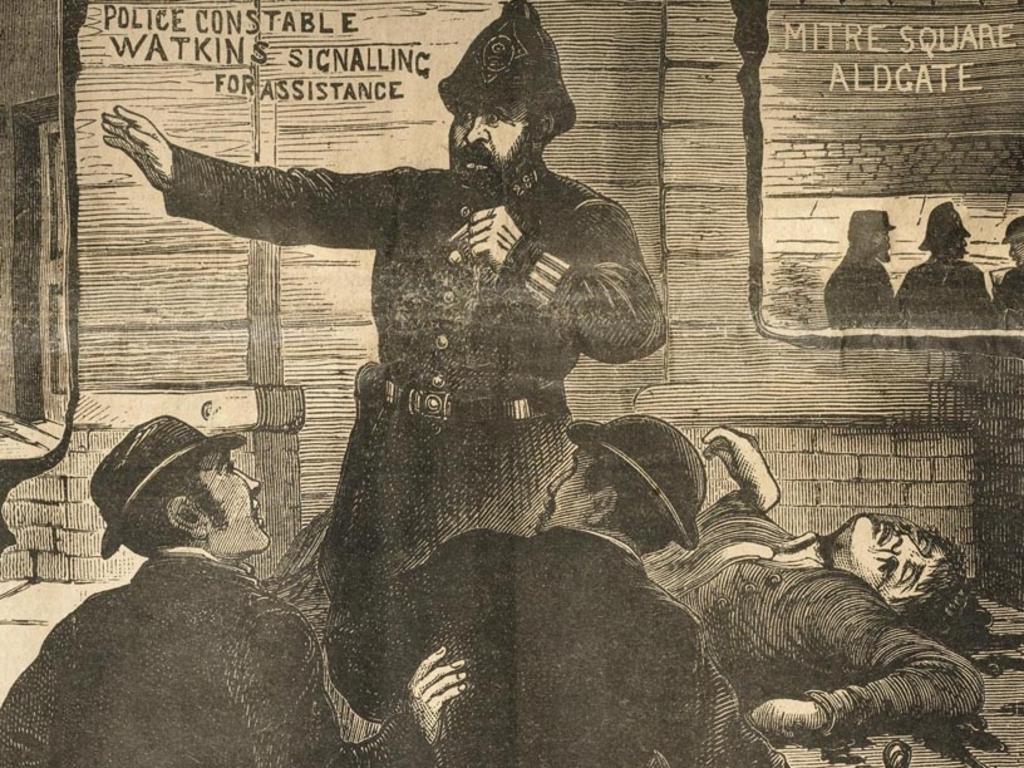

On September 8, Annie Chapman’s body was found, with similar injuries and two slashes to the throat. Elizabeth Stride and Catherine Eddowes’ bodies were found on the same night, September 30 — Stride was found in Dutfield’s yard, while 45 minutes later Eddowes body was found in Mitre square.

Mary Jane Kelly’s mutilated body was found in her bed on November 9 with similar horrific injuries. The killings stood out from other murders due to the sadistic mutilation of the bodies and the fact the mystery of the Ripper’s identity has never been solved.

The story of the Victorian-era serial killer has spawned thousands of books, TV series and films — mostly filled with rumour and misinformation — and one of the biggest myths to arise from the murders is that all of the women were sex workers, as though that made their lives less valuable.

The Five

When author of The Five: The Untold Lives of the Women Killed by Jack the Ripper Hallie Rubenhold set out to write about 19th century sex workers, her immediate thought was that the women killed by Jack the Ripper were the most famous sex workers of the Victorian era and writing their stories would be extremely illuminating.

Ms Rubenhold told news.com.au it wasn’t until she dug deeply into the source material that she realised there was no credible documentation to back up the claims that three of the five victims were involved in sex work.

“Someone like Mary Jane Kelly, who was a career sex worker, left a substantial trail of evidence that she was involved in the trade,” she said.

“Elizabeth Stride was involved in prostitution in Sweden before she immigrated to London and after her husband died, there is a police record that states she was arrested for solicitation in 1884. We have no idea if she had returned to the trade when she died,” Ms Rubenhold said.

“As for the others, these claims are based largely on hearsay and prejudice. Only Kelly had the word “prostitute” written in the section marked “occupation” on her death certificate.”

That information was enough to convince Rubenhold to write a book about the women, to place their lives in context of the murders. She also wanted to explore the women’s lives so they were no longer seen as “only corpses.”

“Whenever the women have been mentioned in the past, it’s almost always in the context of telling the story of the Ripper. It’s as if their lives only mattered in the grand scheme of attempting to figure out the identity of their killer.”

.@HallieRubenhold is flipping the script on Jack the Ripper’s victims — here are the tragic stories of the women subjected to ‘gender crimes’ pic.twitter.com/J9bpTpTsTN

— NowThis (@nowthisnews) July 31, 2019

To unearth details about the women’s lives Rubenhold had to take on the role of a detective.

“Not everyone realises that history isn’t just about reading books and regurgitating ‘facts’ — it’s about going to the source of those facts, digging through them and often finding new things that have been overlooked.

“History isn’t fixed in stone, how we perceive the events of the past is always changing.”

As she began investigating the women’s history, she realised all five women had very different lives and very different stories.

Polly Nichols had been living with her husband and two children in a new building on Stamford Street in Lambeth. (It was the first time they’d lived in a house that had a toilet.) But, due to marital problems brought on by her husband’s infidelity, Nicols was forced to leave the marriage and enter the dreaded workhouse.

The inquest into her death became a judgment on her morals, with the coroner asking her former house mate, “Do you consider that she was very cleanly in her habits?”

According to Rubenhold there was absolutely no evidence that she had ever been a prostitute.

Stride had been forced into prostitution in Sweden but arrived in London and picked up domestic service work. She married a carpenter, then when the couple divorced, she set-up a coffeehouse that turned out to be disastrous. She managed to support herself by promoting herself as a “disaster victim.”

Rubenhold discovered that Eddowes had been travelling around the country selling chapbooks. Clearly very loved, more than 500 people attended her funeral.

There were few details about Kelly’s life, however Rubenhold believes she most likely came from a “good family” and then fell into hard times, forcing her into prostitution.

Tragic lives

In the 19th century, life as a poor, working class woman was a very grim combination. There were few choices when it came to work; women could work in a sweatshop, become a domestic servant or a charwoman (a woman employed as a cleaner in a house or office), or take on odd-jobs working from home. But all of these jobs were poorly paid and involved long hours. It was a life of absolute hardship with little reward.

According to Rubenhold, in Victorian society, women were not supposed to be breadwinners; they were expected to be wives and mothers, not financially supporting a family.

So, if a marriage broke down or a woman’s father or husband died, the cards would be stacked very much against her and she’d end up in the workhouse or on the streets.

Rubenhold was able to reconstruct much of the women’s lives by using several of the newspaper interviews with people who knew them, as well as death records and censuses. She also referenced sources such as Charles Booth’s poverty maps, which were able to chart the geographies of poverty in London.

According to Rubenhold, Victorian society tended to see all “dispossessed women” as prostitutes. For example, if a woman was living on the streets or was an addict, there was the assumption that she was a prostitute.

At the time of their deaths, four of the victims were unmarried women and in their 40s. In the late 1880s the average lifespan for a woman was 48.

Between them, the five women had survived domestic violence, alcoholism, broken marriages and the horrors of the workhouse. Three of them had been homeless and forced to sleep on the streets.

Kelly’s story was different as she was in her mid-20s and working as a sex worker to make ends meet. She was alone and sleeping when the killer broke into her room.

And, while Rubenhold claims the lives of all five women captivated her, it was the stories of Chapman and Stride that she found the most tragic.

“Chapman’s family had moved into the middle class, and it was such a struggle to get there. Her life could have been so much better than it was. ” Rubenhold told news.com.au.

“I was also amazed at Elizabeth Stride and the strength of her character. To have been forced into prostitution in Sweden and then to immigrate to the UK, to have suffered with syphilis and a devastating miscarriage.

“To have worked so hard and married a man with whom she then ran a business, only to find herself slipping back down into poverty again — I can only imagine the toll that would have taken on a person.”

There is still a huge fascination surrounding the Ripper murders. Of course, part of the mystique around the killings is the fact that the perpetrator was never caught.

Sadly, Rubenhold doesn’t believe the majority of people have thought twice about the victims, simply because our culture, taking its cue from the Victorians, never valued the women who were killed.

“It’s only now that we’re beginning to look at how we discuss murder and we’re starting to turn the lens around and examine so many other factors and circumstances surrounding crimes, not only the victims, but the community, the families involved and the series of events and beliefs that allowed such atrocities to take place,” Rubenhold said.

“It’s these things that I find especially interesting. The age-old narrative of why and how a killer killed doesn’t interest me as much as these other peripheral aspects.”

As for Rubenhold’s theory as to who the Ripper might have been? She doesn’t care and wishes to avoids any speculation about his identity.

“It’s time we move on from this parlour game. The greatest justice we can do for the victims is to remember them, not him.

“I love the idea that readers are moved by the stories of the victims and that they now consider them as people, not just footnotes to a story about a killer,” Rubenhold said.

“The more people who feel they’ve been touched by these five women’s lives, the more chance we have of totally turning around the Ripper narrative so it’s not all about him. Only then will we be able to kill off the murderer once and for all.”

LJ Charleston is a freelance features writer. Continue the conversation @LJCharleston