Teen’s Gold Coast gang rape by Aussie surfers ignored by police

When Karen Iles was just 14 she met a group of Aussie surfers who gang raped her. What the police did afterwards is unforgivable. Warning: Distressing

EXCLUSIVE

On International Women’s Day 2004, Karen Iles walked into Newtown Police Station. She was there to report a gang rape.

Years earlier, while holidaying with her family in the Gold Coast, the Year 8 student was lured into a hotel room by a “surfer dude”. There, 14-year-old Karen was held down and brutally gang raped by up to 15 men and teenage boys, as others stood by watching.

What she provided to police in 2004 should have been enough for an arrest. Or at least an investigation.

What really happened is unforgivable.

Now, Karen is speaking out in detail about the rapes and why she is campaigning for reform. This is her story.

**************************************************************************

When Karen and her friend Alice* headed to Coolangatta, Queensland during the October school holidays in 1993, the Gosford, NSW teens expected to come back with nothing more than a sun tan and some fond memories.

“I had just turned 14,” says Karen, now aged 43. “I had my first ever proper bikini. We expected to spend the days sitting around at the beach, body surfing and hanging out swimming.”

Along with Karen’s parents and younger brother, the girls were staying at the Rainbow Commodore Holiday Apartments.

Unbeknown to them, also staying in that same complex, and other apartments nearby, was a notorious surf gang.

“Alice and I were in the spa and a group of them just joined in,” Karen says.

Over the following days the girls, who attended an academically selective high school in NSW, would run into the surfer group at the pool or down by the beach.

“There were about 20 of them aged between 15 and their late 20s,” remembers Karen.

Midway through the trip, one of the surfers invited Karen over for lunch and to watch television.

“The TV was on and one of them rolled a joint and proceeded to pass it around. I remember saying ‘no I don’t want any’,” says Karen, who had no experience with drugs.

One of the older surfers then took Karen’s hand, pulling her into one of the rooms, closing the door behind him.

“At first I was quite confused with what was going on. I’d never so much as kissed a boy before that trip. He walked up to me and put one of his hands on my shoulder and started pushing me backwards. He was saying things like ‘Come on, it’ll be OK, just trust me’.

“I said ‘No, what are you doing?’ He kept repeating, ‘It’s OK just trust me’.”

The man then pinned Karen down and began aggressively kissing her.

“I started to struggle and kick and to be quite vocal. I was saying ‘No stop, get off me.’ I had just turned 14. I wasn’t a big build. He was a 21-year-old surfer dude,” Karen says.

“At that point, other males filtered into the room. I was struggling, saying ‘No, stop it hurts, it really hurts’ and ‘No, stop, stop! I don’t want to do this’.”

Two of the men then held Karen down while others took turns assaulting her.

“I remember thinking to myself I needed to get out of there. I opened my eyes and looked around. By then there were at least 15 boys and men in the room.

“They were saying derogatory slurs and egging each other on. The older ones were directing and taunting the younger ones – the 15 and 16-year-olds – saying ‘c’mon you’re not a virgin are ya?’ and shaming them into doing it [raping me].

“They were very orchestrated and methodical.

“I can remember thinking to myself that there were too many boys in the room and I wouldn’t be able to get out. So I closed my eyes and thought: ‘I hope it’s over with as soon as possible’.”

For Karen, her world as she knew it ended in that moment.

“I was considered a ‘good girl’. I was studious and academic. I played netball, took piano lessons at the Conservatorium of Music in Gosford, took art classes and had a wide circle of friends,” Karen says.

“I came from a very stable and loving home. My dad worked for the local council and my mum worked for the district court, managing the recording and transcribing of court proceedings.

“At that time, I wanted to be a lawyer as I was heavily influenced by Mum’s job and shows on TV like LA Law.”

During the gang rape, though, all Karen thought about was survival.

“I grew up in a time when the horrific assaults and murder of Anita Cobby was in everyone’s mind. I remember in the first minutes [of the gang rape] thinking about Anita Cobby and [another, separate] case my mum had told me about: a young woman had been abducted and put in the boot of the car and had the presence of mind to rip off her finger nails and put them under the carpet in the back of the boot,” Karen says.

“So during the rapes, I thought about Anita Cobby and I thought about that young woman and I thought, ‘I need to just survive this. And they will stop. They will eventually have to stop’.”

Finally, the room did begin to empty out. “For a while I was just laying there, paralysed and in shock. Then one of the men stuck his head back in and said ‘Come on slut, put your clothes back on’.”

Dazed, humiliated and in pain, Karen gathered herself and left in search of her friend Alice.

“When we got home, Mum and Dad were down at the beach. I showered and then just wanted to pretend like it never happened.”

It was a long drive back across the state line, home to NSW’s Central Coast. Karen returned home a different person.

“After the assault my aspirations changed dramatically. I’d been an A-Grade student but afterwards, I didn’t want to complete Year 10. I wanted to drop out of school and work at a cafe,” she says.

“At 14 you have no further context to understand something like gang rape, so you blame yourself.

“At school I immediately changed friendship groups. I was in the popular ‘good girl’ group, but I started to sit with the ‘naughty group’ down the oval, smoking.

“I began to dress in dark grungy clothing and wag school … In Year 11 and 12 I shaved my head and developed anorexia. I also started taking a lot of drugs: smoking pot, LSD.

“I dropped piano and netball. Later I got a boyfriend who would steal things and do graffiti. My parents hated him, of course.

“There was just a very distinct break with who I was, who I hung out with, and how I dressed after the assaults.”

The sudden shift in behaviour did not go unnoticed. Gone was the little girl who only months earlier was riding bikes and watching shows like The Simpsons and The Wonder Years.

It was enough to raise her parent’s suspicions.

“A few weeks after we arrived home, Mum and Dad found my diary and pulled me out of school for the day.”

Karen had written a diary entry about the rapes.

“Mum and Dad had read it. They sat me down in the lounge room and confronted me with the diary,” Karen says.

Photocopies of Karen’s teen diary obtained by news.com.au show that she had also written about her fears of becoming pregnant following the assaults.

“Mum and Dad were so upset about what happened to me,” says Karen.

“During the conversation they told me they could get the boys in a lot of trouble for what they had done to me. But at the time, I still thought it was my fault and I didn’t want to get anyone else in trouble.

“I was blaming myself and experiencing a mix of shame, self-blame and minimising … I’d been wearing my first proper bikini – and at 14 I honestly thought I was at fault because of that.”

Her mum’s job was another factor as to why Karen didn’t want to report the rape. She knew the reality of what was happening inside courtrooms.

“As a family we were always very open about the justice system and how it is so broken: how victims in rape cases go through a lot of pain for likely no outcome. I knew, instinctively, that reporting would cause more trauma,” Karen says.

I don’t want this to happen to others

And so for years, Karen stayed silent about the gang rape. Looking back, the symptoms of trauma were rippling from her body like neon waves. Yet at the time those signs were misinterpreted by teachers and others as teen angst.

Still, as Karen grew, so did her courage and understanding of the situation.

In Year 10, she read Germaine Greer’s The Female Eunuch. “One line describes a woman as ‘a human spittoon’. That resonated,” she remembers.

In Year 11 and 12, Karen obsessively threw herself into her studies achieving a TER (now ATAR) of 97.55.

The impressive mark was enough to land her a place studying Law at Macquarie University. Moving out of home, Karen connected with the campus Women’s Movement, where she would soon meet Karen Willis, the then executive director of the NSW Rape Crisis Centre.

“I had always known it was rape, but I hadn’t really owned it or grappled with it until then,” Karen says.

Finally, in February 2004, a news story broke that sent a shockwave through Karen. A 20-year-old woman had made a police report, alleging a gang rape involving six members of an NRL football team at a Coffs Harbour resort.

The prosecution would ultimately abandon the case, and no charges were laid, however the high profile incident sparked widespread conversation about gang-rape and male ‘pack behaviour’ in the Australian press.

“I just remember thinking ‘gosh this is familiar’,” Karen says.

That was the turning point; the catalyst.

As a second year law student and campus Women’s Officer, Karen was also developing a growing knowledge of her rights and options.

“I knew there was no limitation period on reporting child sexual abuse. I knew that in Queensland the offenders could each be facing a life sentence for what they had done. I knew consent would not be an issue as a 14-year-old child cannot consent.

And so, on International Women’s Day 2004, Karen walked into Newtown police station ready to report her gang rape.

“I hoped [that by reporting] something would happen to stop them. I hoped other women would come forward. That the police would stitch it all together,” she says.

News.com.au has obtained a photocopy of the 15-page handwritten notes made by the officer who took Karen’s initial statement on March 8, 2004.

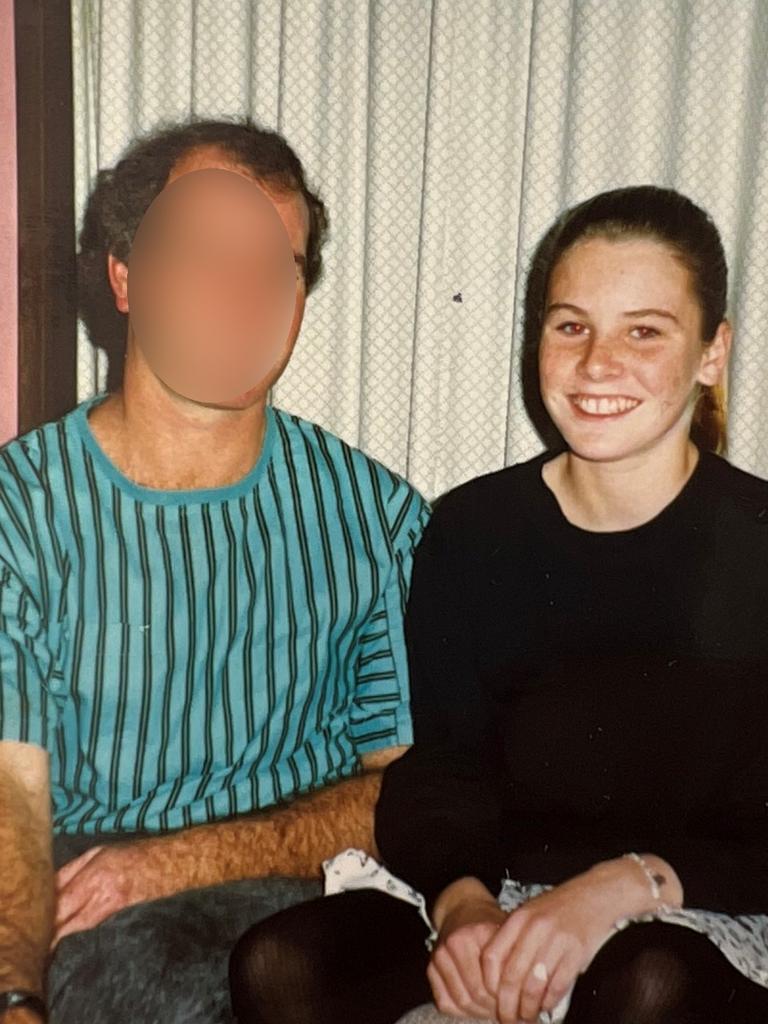

Fifteen days later, Karen then visited Redfern Station where she gave a more extensive 12-page typed statement, and provided names, a photograph of one of the offenders, maps of the location, pages from her diary and other details which news.com.au has also obtained a copy of.

And then she waited. And waited.

“I was promised that my parents would be interviewed,” says Karen.

“I was promised that the statement I gave at Redfern was the first of a number of statements and I was promised a joint investigation by Coolangatta and Redfern police.

“I didn’t assume these things from watching TV. I was told this is what would happen and that they would knock on the door of [the male individual] whose full name and photograph I had provided them with.”

Instead the police shut the investigation mere days later without ever interviewing a single soul.

Not that Karen was told any of this.

Instead Karen believed that both Queensland and NSW police were on the task.

“It was phone call after phone call of me getting fobbed off or being told that they were waiting to make contact with the other police jurisdiction.

“It went into a black hole of mishandling. Up to 2018, I would sporadically pluck up the courage to call both Coolangatta and Redfern police and leave messages, but there would be no call back,” says Karen.

“Then in 2018 on one of these sporadic calls I spoke to a desk clerk at Coolangatta … she looked up my file number and she said that my statement had been shredded, destroyed [in Queensland]. She said ‘this all looks very weird, odd and strange’.

“She then referred me to a new police officer and he said we don’t have anything on file and asked me to try to retrieve it from NSW. I expressed extreme distress at that.”

At the time, Karen was working in a Sydney law firm. Once again she visited Redfern Station to try to unscramble the mess and get an investigation moving. Once again, she expected action.

“Again, nothing happened. I then became very suicidal,” she says.

Every aspect of Karen’s life was now affected. She attempted to get into counselling but was rebuffed because the matter was considered historical.

Finally during the 2021 Covid lockdowns, Karen once more plucked up the courage to follow the matter up with Redfern.

To her dismay, she was now told the truth: the matter had been shut for well over a decade.

“In 18 years no one had told me that my file had been shut a week after I had made my original complaint.

“At that point I put in a complaint and started making Freedom of Information (FOI) requests.” Karen also engaged her own lawyer.

FOI requests showed that Karen’s case had been assigned to Queensland detectives but stalled due to inaction from NSW detectives. There is no evidence a substantiative investigation ever took place.

A letter from NSW police said they had undertaken “extensive searches” for information but that a case file “did not contain any documentation”.

“I acknowledge that an error in record keeping has resulted in a copy of your statement no longer being available from the NSW Police,” the letter said.

Later in 2021, without explanation, police located a copy of Karen’s 2004 statement which news.com.au has sighted.

NSW police said they had conducted a review of the matter in December 2021 and have invited Karen for a meeting.

Campaigning for change

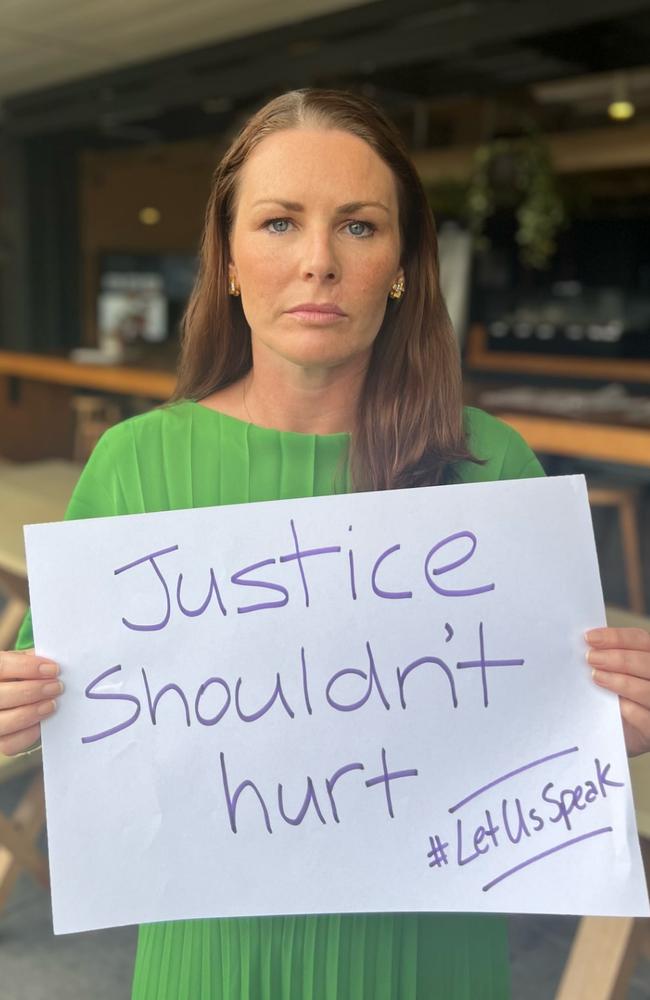

Karen has now launched a public campaign asking the Attorneys-Generals from each state and territory for a legally enforceable duty of care to be given to victims of serious crime.

“Currently there is no legally enforceable duty of care owed to victims of serious crime,” she says.

“Police have their own internal operating protocols but they are not legally enforceable,” Karen says.

“People are in absolute shock and disbelief when they hear my story.”

Already over 20,000 people have signed Karen’s petition for reform.

She argues that a minimum set of standards must be met in investigations.

“There are basic steps which any member of the community would already expect police to do such as: interview persons of interest; not destroy evidence; interview witnesses; and communicate with the victim where things are up to,” Karen says.

“What shocked me in 2021 when I was going through the complaint process, was that there is no legal statutory duty for police to investigate serious crimes … That means that victims have no legal recourse when the police have been negligent in the conduct of their duties.

“You need truly independent bodies to review police conduct and how they have made decisions about investigations, and that body should not be staffed by police or ex police. It should be a permanent body.”

Karen says there is also a double standard in that offenders are owed a duty of care, but their victims are not.

“If you are in custody as an offender, you have legally enforceable rights because there is a duty of care. But if you are the victim of the crime, there is not that same duty. There is a charter of rights, but it is vague, and not legally enforceable.”

Karen says she has chosen to share her story in full, as she believes her own experience is “a really familiar story”.

“Police are gatekeepers; they get to filter out who can and cannot access justice. They get to exercise discretion – based on their personal biases – regarding which cases they choose to investigate.

“It’s not a level playing field. In my case I present as educated, articulate, professional and I’m a lawyer myself, yet still I got no justice – so what hope is there for anyone else?”

Click here to sign Karen’s petition

* Names changed