Shocking sexual assault statistics revealed as more victims come forward to news.com.au

FOI documents released to a Sydney uni student paint a damning picture of life on campus, as more victims come forward to news.com.au.

OVER the past five years, the University of Sydney has failed to inform police of almost two thirds of all cases of rape, attempted rape, and indecent assault reported on campus, new documents reveal.

Tom Joyner, a current editor of Sydney University student newspaper Honi Soit, published the findings after obtaining internal university data under freedom of information legislation.

The documents reveal that between May 2011 and May 2016, the university received a total of 17 formal reports of rape, attempted rape and other indecent assaults involving students, but only six were ever referred on to police.

Anna Hush, the current Women’s Officer at Sydney University, said the figures are disturbing.

“The university is obliged to report all claims of sexual assault and indecent assault to the police however the report reveals that police were only informed in around a third of cases. Clearly the university doesn’t take these issues as seriously as they publicly purport to.”

Perhaps more concerning, a separate report prepared by Sydney University earlier this year has found that only one per cent of their students who have experienced sexual assault or indecent assault during their time as a student ever make a formal report to the university.

“There have been 17 formal complaints in the past five years. If the university’s own figures are accurate, this would suggest that up to 1700 incidents of sexual assault, indecent assault and acts of indecency involving students have gone unreported to the university in that five-year period,” said Joyner.

“That would suggest an estimated 340 incidents each year, a rate close to one every day”.

“It’s shocking and difficult to fathom. Of course universities have a vested interest in protecting their reputation [by concealing or disputing such statistics]. It’s very damaging from their point of view for there to be transparency, because who is going to want to enrol, or let their child enrol at a university where sexual assault is occurring.”

A representative for the university has responded to news.com.au, stating that “the University recognises that there is a general trend of underreporting”, however “the two datasets are entirely discrete and therefore no specific conclusions can be drawn from a comparison.”

It should also be noted that a significant number of assaults involving students happen off campus.

Regardless, both documents are highly troubling.

Joyner, who personally funded the freedom of information requests, said he got the idea after attending a screening of The Hunting Ground, a documentary that examines the institutional cover up of rape on American university campuses.

“In America, there is a federal legal instrument which requires universities to publish crime data, including for sexual assault. But we don’t have such an instrument in Australia, which makes it very easy for the university to be opaque about sexual assault data.

“I was interested in how transparent [my own university] has been. The university keeps a vast number of records, but when I’ve written stories in the past on all different topics, I’ve often had trouble coming up against institutional barriers, bureaucratic stumbling blocks and endless hoops to jump through. It’s extremely frustrating” says Joyner.

For comparison sake, Joyner also submitted freedom of information requests to four other universities in the state: UNSW, Wollongong, Newcastle and Western Sydney.

“Overall I got very different [styles of] responses from each university even though I made the same request to each. There was a lot of discretion in how transparent they were” says Joyner.

“Sydney University, Western Sydney, Newcastle and UNSW were compliant, although UNSW didn’t give much information — they gave a very narrow response.

“Wollongong University suggested — rather ridiculously — that instead of asking for sexual assault data I should reframe my request and ask for information on what the university is doing to tackle sexual assault” said Joyner.

According to the FOI request, all sexual assault cases reported to Wollongong University in the past five years were also reported to the police, but not a single one resulted in any disciplinary action from either the courts or the university.

“Sydney University, Newcastle, UNSW and Western Sydney University all reported taking some disciplinary action against some of the perpetrators at least some of the time. Wollongong was an aberrant outlier in that regard.”

Andrew* is just one of those victims who has been left feeling betrayed by Wollongong University after he reported his alleged sexual assault to them earlier this year.

As news.com.au reported last week, Andrew presented Wollongong University with a copy of an Apprehended Violence Order that police had granted him against a fellow student following a reported sexual assault.

But despite having the AVO in place, the university advised Andrew that it was his responsibility to “avoid contact” with the offender.

In a leaked document, Andrew was told that he “should avoid contact with [the person named in the AVO]. Should [that person] be sighted while on campus [Andrew] should stop and select a different pathway to one which would continue any opportunity for contact”.

According to Ellie Greenwood, a representative for End Rape On Campus Australia, the university “absolutely let Andrew down.”

“They have expressed the idea that it is Andrew who must change his behaviour to be safe, [but] the perpetrator does not have to change in any way. It is even more disturbing that the university took this action when an AVO was in place. A court had already looked at Andrew’s case and determined that an AVO was justified. If universities are not going to take a court order seriously, and act to protect the mental and physical safety of their students, what will it take?”

Since Andrew’s story broke last week, news.com.au has been contacted by multiple current and former students around Australia who have alleged that their own university failed to act on sexual assault complaints.

In one instance a student alleges she was told by university staff not to talk to friends about her rape because it would impact on the perpetrator’s privacy.

In another, a student claims that she was told there was nothing that could be done because she was drunk at the time of the assault.

In a third case a student claims that she was reprimanded by university staff for discussing her rape on social media.

In yet another case, a student was guilted into silence by a college staff member who told her that reporting to police would ruin the perpetrator’s life.

Ariel* — a 20-year old student at the University of Melbourne can relate.

Ariel says that in October 2014, she was raped in her residential college by a man she had been friends with since O-week that year. Ariel was semiconscious and unable to speak at the time the alleged assault began. Eventually it ended, after a witness walked in to the room and interrupted the assault.

But when Ariel reported the rape to her college she was silenced and told to stop talking about the assault on campus. “The college told me not to call it rape, because that language was too strong, too inflammatory.

“I asked the administration to inform my parents but they hesitated and tried to talk me out of it. They also told me not to talk about it in the dining hall or around college, because they said it could ‘hurt my case’. It was a vague, veiled warning, but it had its desired effect. I was like ‘well I don’t want to hurt my chances, and if talking about it could put it in his favour then I better stop [talking]’. [Looking back] it was very manipulative and very silencing.”

Sharna Bremner from End Rape on Campus Australia says that, “in rape cases, it’s not uncommon for institutions to use ‘gaslighting’ techniques — which undermine victims by silencing and psychologically manipulating them, and making them doubt their own decision to speak up”.

Ariel says that she was told that if she wanted to pursue the matter with the college, she would be required to sit before a formal disciplinary panel which included a lawyer, a college staff member, and a fellow college student, and that the perpetrator would also be offered the chance to challenge her version of events.

“They said that our friends would also be brought in, to get a sense of both of our characters. My initial thoughts were ‘I can’t go through that’. The thought of having to retell the entire event in detail is just horrific, and to essentially be interrogated and cross examined to see if I’m telling the truth felt really invasive. Having to say it in front of one of my own peers [would have been] awful. The fact that they were using the same process they use to resolve matters like petty theft between students made the whole thing feel very trivialised, like they didn’t understand the gravity of what had occurred.”

“The process shows no understanding of trauma and would exacerbate existing distress” says Bremner.

“To ask a student to disclose in front of one of her peers, knowing how close college communities are, raises serious concerns about privacy and confidentiality. Being outnumbered by a panel of people which includes a university lawyer is intimidating enough, the power imbalance it creates would be extraordinary.”

Ariel decided to take her case to the police instead. The male student was arrested, but the case was never prosecuted because of lack of evidence.

Meanwhile, back at the college, Ariel’s decision to involve police was met with strong backlash from fellow students. “One person said ‘oh but you can’t blame him if he was drunk’. That was their honest view point. Other people said things like “Oh don’t you think that [involving the police] is going a bit far? Hasn’t he been punished enough? There’s a chance he could get thrown out of college.

“Other people said things like ‘involving the police, oh wow, isn’t that a bit extreme? Aren’t you just out for vengeance now?’ People had this opinion that it should all be resolved by the college and [they had this view of] ‘why would you drag the outside world into this when it’s a college issue?’”

Both Ariel and the man she alleges raped her are still students at Melbourne University.

“Pretty much every single day I walk onto campus and turn a corner, and think ‘what if he’s here? What if I see him?’ I still have anxiety every single day on campus.”

Ariel has since left the college, but the man in question continues to be allowed on their grounds. “I find it appalling that he was allowed back on that land. I kicked up a fuss and refused to be quiet about it, but there are still no repercussions for him.”

Ariel’s story follows a controversy earlier this year where students at Melbourne University were encouraged to rate female students on their appearance.

“She’s a bitch and has bad breath” and “This girl is a 0/10. I would not bang her even if they paid me” were just some of the comments posted on the Facebook group, which also revealed the location and class timetables of certain women.

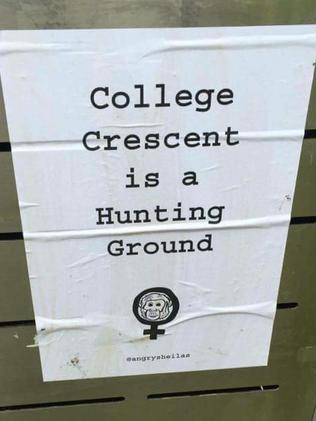

A month after that episode, the University was embroiled in another scandal after posters mysteriously appeared on campus with slogans including “College Crescent is a Hunting Ground” and “Why don’t the UniMelb colleges record the number of sexual assaults that happen there?”

According to multiple experts Australian universities across the board need to do better.

Dr Michael Salter who is a senior lecturer in criminology at The University of Western Sydney says that university responses to sexual assault “tend to be ad hoc and highly legalistic”.

“A bureaucratic response is the exact opposite of what a person in that positions needs. A feeling of institutional betrayal significantly increases the likelihood that a student will develop long term traumatic mental health issues. It’s a key opportunity to provide support and care and if that opportunity is missed, it directly causes harm to students.”

“Universities really haven’t taken on board their responsibilities around prevention of sexual violence and victimisation within their own community” says Dr Salter.

“They have been quite slow to take that up compared to say, the United States, where since at least the late 1980s there has been an expectation that the university will take quite active steps to prevent sexual assault. Australian universities just haven’t had that proactive response and because there is no collective ownership of that mandate within higher education, when victimisation takes place, the university is really on the back-foot”.

“When that background community of care is absent, which is the case at the moment, then uni’s are defaulting to this very legalistic, bureaucratic view. Until prevention of violence and awareness around sexual assault is just embedded as part of a general university culture, the response [will continue to be] highly individualistic and reactive and the onus [will continue to] fall on victims to [advocate for themselves], rather than being able to relax back into an environment where they feel confident that they are believed” said Dr Salter.

“I think it would be in everyone’s benefit to take this on to improve student safety, improve student wellbeing, and increase the educational opportunity and achievement for students impacted by sexual violence.”

Nina Funnell is an author and journalist. She tweets @ninafunnell

If you or someone you know has been impacted by sexual assault or domestic violence, support is available at 1800 RESPECT.

*names have been changed