Saxon Mullins shares what Aussies still get wrong about consent

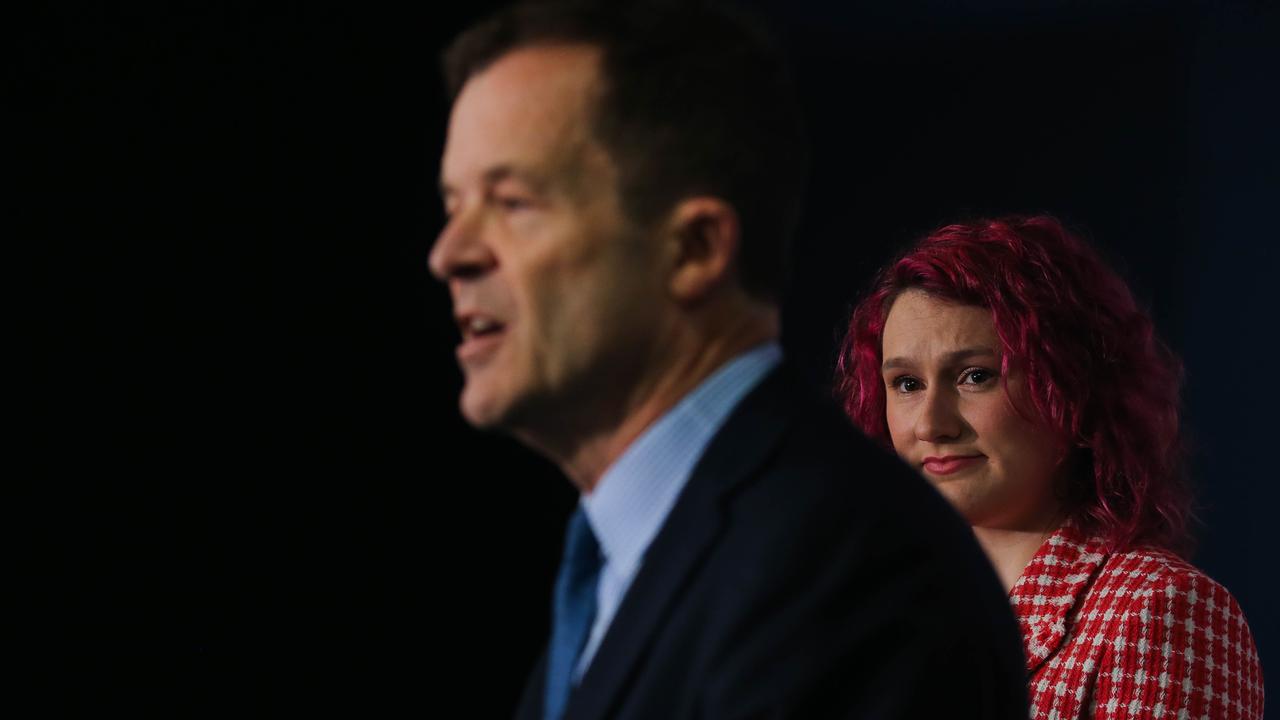

Survivor and advocate Saxon Mullins has shared the one thing we still get wrong about one of Australia’s most “red hot” issues.

“Why did I start dancing with him? Why did I leave my friend? If I ‘really didn’t want it’, then I would’ve physically stopped him.”

These are the kind of intrusive questions that were levelled at Saxon Mullins during her five-year-long court battle in which the man she accused of raping her in a Kings Cross alleyway in 2013 was eventually acquitted.

The case that shocked Australia finally ended after Judge Robyn Tupman found the prosecution had failed to establish “reasonable grounds for believing the complainant was not consenting” to sex.

Ten years on, these sorts of questions are still levelled at sexual assault survivors in courtrooms across Australia every day.

“Questions about why I did everything I did,” Ms Mullins, now 28, says in journalist and author Jess Hill’s Asking For It, a TV series examining our “red hot” national conversation around consent.

“And no questions about why he did everything he did – why there was no one-second question to ask if I wanted to have sex.”

As the survivor and advocate – who spearheaded the campaign for NSW’s Affirmative Consent laws – told news.com.au, “looking at consent in isolation makes it seem almost too easy – and yet we’re still not even sort of doing that part of it”.

“We try to divorce it from the understanding of how relationships work, and bodily autonomy, and all of these other things. We try to separate it to make the issue of consent and sexual violence and relationships seem that little bit easier,” Ms Mullins said.

“We look at it on its own and say, all you need to do is say, ‘Hey, do you want to [have sex]?’ and the other person says, ‘Yes.’ And while that’s definitely a massive part of it, there are so many other things that feed into that.”

Not only is consent “of course” about sex, relationships and respect, it also, Ms Mullins explained, boils down to our view of sex in general – which is “that it is not an experience of consenting people, but rather something you ‘have’ or something you ‘do’” to someone else, instead of something two people, as equals, do together.

“Our idea of sex is [that] it starts and then it has an end – but everything that happens in the middle is still part of sex. It’s still really important,” she added.

“It still does vary between things. It’s not exactly the same the entire way through.

“And even if it were – sometimes I get halfway through an episode of a show I love and I’m like, ‘Actually, nah, I don’t want to watch this anymore’. People are complicated! And sex is complicated.

“And that’s why you need to have an open dialogue. I’m not saying that every single second of sex you have to be [saying] ‘Yes, yes, yes’ or whatever, but it’s about having that conversation and keeping in check how your partner’s feeling, how you’re feeling, and then communicating those feelings to each other.”

Using Ms Mullins’ story and those of other survivors and advocates to start the conversation, Hill interrogates how we, as a nation, can replace our “rape culture” with one of consent in the three-part SBS series.

“What would happen if we were more willing to give survivors the benefit of the doubt? What if we didn’t routinely question if it was really ‘that’ serious, or why they ‘didn’t just say no’? Or if it even happened at all?” Hill asked in last week’s episode.

“Would we see an increase in the number of survivors willing to report? And what kind of impact would that have on our society?”

Asked if the outcome – and the way she was treated inside the courtroom – might’ve been different, had questions like these been considered when her own case was before the court, Ms Mullins is dubious.

“When you think about the conversations we’re having now around sexual violence, around family and domestic violence, all of those things – if you look back not long ago, we have had these conversations before,” she said.

“And that’s not to say that we’re stuck in this cyclical jail that we’ll never get out of.

“But we have to be committed as a community not just to continuing to have a cursory conversation about this, but making sure those conversations actually lead to change, and making sure those conversations don’t just stay within the confines of a safe friendship where we know we have the same ideas and we can be in an echo chamber.

“We’re making sure that these ideas are really spreading across our communities and our society. There is a potential that some views that could have been different, some things could have changed.

“But I wonder if, even at this point, we’re having a serious enough conversation for those ideas to infiltrate the courtroom.”

A “huge, huge part” of further moving the dial on our attitude toward and understanding of consent, Ms Mullins said, is “having relationships and sexuality education from day dot – young, young kids learning about their bodies and all of those tiny conversations that actually lead into really big ideas, and really big fundamental understandings from within”.

“The other part – which seems to me to be easy, but apparently is not – is not letting this kind of behaviour slide,” she said.

“And I don’t just mean in friendships or families – I think people do have some understanding that they’re meant to call their friends out when they do something wrong.

“But our politicians, people in our justice system, police officers: we are allowing people who are the arbiters of our justice to perpetrate the violence of which we’re trying to seek justice.

“How can we work within a system like that?

“Someone who is in a position of power, and they’re not being called out for their bad behaviour – it continues that cycle of, ‘Well, I would never do it, but I’m also not going to say anything about it.’

“You’re not helping. You’re perpetuating – that person thinks that their behaviour is OK.”

While she “can’t imagine” Australia’s crisis of sexual violence is something “that’s going to [come to an end] tomorrow … I think that we are working towards that”.

“It seems like, when we get little wins – even the Affirmative Consent law changes, that’s a small win in the grand scheme of things because it helps a specific process, and it helps people to understand consent,” Ms Mullins said.

“But really the end goal of everybody who does this work is to end sexual violence in Australia.”

The second episode of Asking For It airs at 8.30pm April 27 on SBS and SBS On Demand