‘Postcode injustice’: The 60,000 children NSW has failed

Since 2016, nearly 60,000 children have reported sexual abuse to NSW Police — and more than 95 per cent of these have been failed by the system.

In the past six years, nearly 60,000 children have reported sexual abuse to NSW police. And shockingly, more than 95 per cent of these children were unable to access a program designed to make it easier for them to give evidence in court.

Now, two sisters from regional NSW have called out the NSW Attorney-General to demand justice for all children.

On Monday, news.com.au exclusively revealed the stories of Rose and Pippa Milthorpe, aged 14 and 17 respectively.

The sisters were just 7 and 11 when they went to court to give evidence in the trial of their abuser. Both say the court process left them more traumatised, despite getting a partial conviction. The offender was convicted of six of eight charges of indecent assault against Pippa. Those against Rose were ultimately dismissed due to her age.

Six years later, they have returned to court and won the right to tell their stories under their real names. They are fighting to have a program rolled out statewide that makes it easier for children involved in sexual offence matters to give evidence.

The program, currently operating in just two locations in Sydney and Newcastle, has received glowing reviews. In April 2019, it was extended through to 30 June 2022, and this year it was extended again to 30 June 2024.

Attorney-General Mark Speakman said the government was “committed to the ongoing delivery of this important initiative” and confirmed in writing to news.com.au that the program would be funded “on an ongoing basis”.

However, the Justice Shouldn’t Hurt campaign is calling for the program to be rolled out consistently across the entire state.

“We live in a rural community, we live in a small town, so we don’t really have access to certain services,” Pippa, from Albury in NSW, told news.com.au.

“Obviously a lot of people in NSW don’t live in the cities. It’s an injustice in itself not being available for everyone. So we think it’s important that it gets to every corner of NSW.”

Mr Speakman praised the sisters’ “extraordinary courage” in speaking out and acknowledged that “giving evidence in court can often be re-traumatising”.

He also pointed out that NSW was a national leader as the only mainland state to have something like the Child Sexual Offence Evidence Program.

But he refused to commit to the rollout of the program across NSW.

“The NSW Government continues to look to expand the program’s reach across the state,” he said in a statement.

Justice shouldn’t hurt, but for children in Australia, it does. The NSW government knows how to fix this problem, but has failed to do so. That’s why news.com.au is calling for law reform to make it easier for child victims of sexual abuse to give evidence. Join the movement and sign the petition here.

‘It shouldn’t be a postcode lottery’

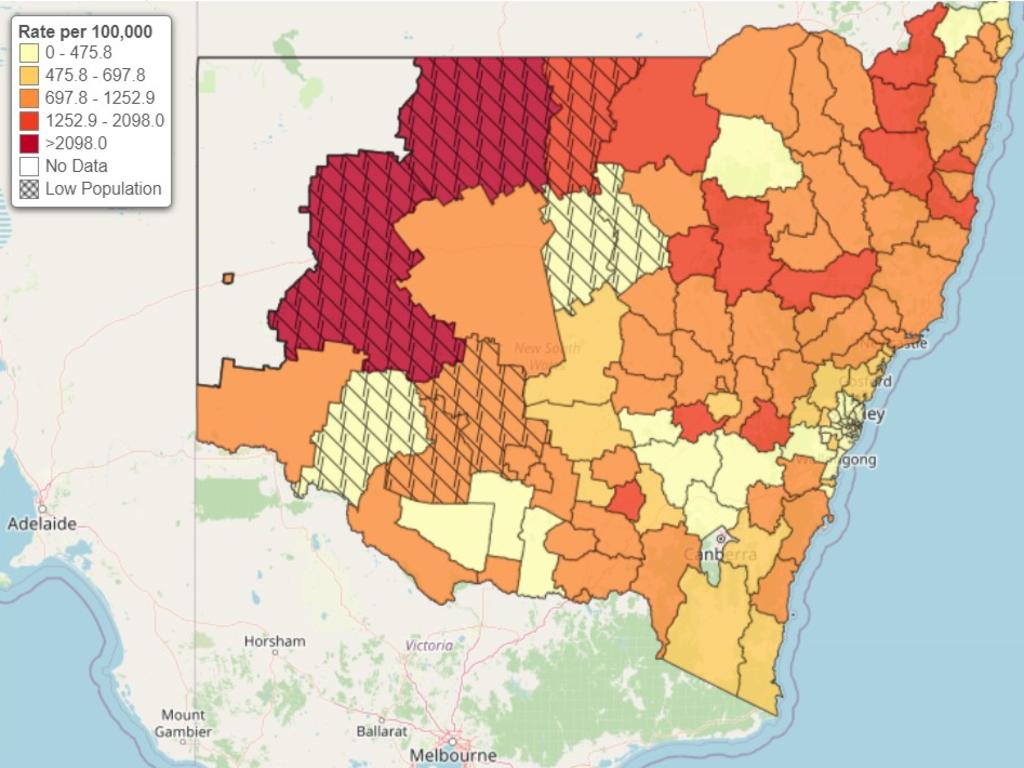

This morning, an exclusive deep dive investigation by news.com.au into the most recent Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research (BOCSAR) crime data revealed an alarming trend in NSW.

The data confirmed what experts have been saying for years: that sexual abuse against children can happen anywhere, but children located in regional, rural and remote areas face much higher victimisation rates.

Yet paradoxically, only metropolitan children located in Sydney and Newcastle are able to access the Child Sexual Offence Evidence Program.

For all other children – particularly those in regional and remote areas – they are left without.

It’s a cruel double standard which means that some of the children who are most at risk of experiencing sexual abuse are now hit with the double-disadvantage of then being least able to access justice support.

According to BOCSAR data, since the program’s launch six years ago, 59,072 children have reported being sexually abused to NSW police.

And only a fraction of those reports, 4.1 per cent (or 2428), came from children in the Sydney or Newcastle LGA where the program operates.

What we are fighting for

Rose and Pippa want the Child Sexual Offence Evidence Program rolled out across NSW.

The program aims to provide greater support to child complainants and prosecution witnesses in sexual offence matters – an experience that is often stressful, harrowing and re-traumatising in itself.

Implemented at the Newcastle and Sydney’s Downing Centre District Court locations as a trial in March 2016, the program has two major components: allowing children to have all of their evidence prerecorded early; and to be supported by specially trained and accredited specialists, known as witness intermediaries, who help them communicate with police and the court, while preserving the rights of the accused to a fair trial.

What currently happens to children in court

Rose and Pippa were seven and 11 when they spent days giving evidence, separated from their parents, and forced to answer questions they feel were designed to try to trip them up.

They had to relive the worst moments of their lives repeatedly, once, in Rose’s case, because a person in the jury fell asleep, forcing a new jury to be empanelled.

What happens to children in our courts is unacceptable. It was pointed out to Director of Public Prosecutions solicitor and chair of the Sexual Assault Review Committee, the late Amy Watts, in 2013 “on a number of occasions” that “the process of manipulation by lawyers of what children and vulnerable witnesses say in cross examination is abusive and violates” their human rights.

“The process confuses the child, uses language and language structures they do not understand and employs suggestive or leading and repetitive questions by adults who are forensically trained in the cross examination/advocacy techniques. It is an unfair playing field,” Ms Watts wrote in her research, conducted as part of the Churchill Fellowship.

What the program does differently

What the program does, University of Sydney Professor Judy Cashmore, who helped complete both independent evaluations of the program, is level that playing field.

“Having to tell someone else about what had happened, or what was alleged to have happened, in court … That’s quite a heavy burden on children, particularly when they’re stressed,” Prof Cashmore told news.com.au.

“So being able to provide a less stressful environment, and one in which somebody else is able to facilitate, negotiate the language that’s used, and assess whether or not a child is able to actually understand those questions, or whether those questions are unfair and confusing, is very important.”

This is the role of the witness intermediary – to act as an “interpreter”, assessing the communication needs of the child and providing a report of this to the court before they give their evidence.

“Basically it means that you have police and lawyers and judges who can be more confident that the questions they’re asking are understood by the child, and if there are concerns about whether or not the child is confused, then the witness intermediary can provide that feedback,” Prof Cashmore said.

“Justice is about having the best available evidence before the court – and that means having a child who’s less stressed, and one who understands the questions they’re being asked.”

She pointed to a 1988 study by Mark Brennan, that involved him asking children of the same age as complainants to “repeat the question” the latter had been asked in court.

“And they couldn’t even repeat it, or maintain the sense of the question. They weren’t in court, they weren’t feeling as though they were under attack, and they possibly didn’t have some of the disadvantages of the complainant,” Prof Cashmore said.

“So if they can’t do it in those circumstances, what we are expecting children in court to do without some assistance?”

Traumatised children shouldn’t have to wait

The other main benefit of the program is that children can give their evidence “quite early on”, captured in a recording, which means it can be used in appeals, or if a trial aborts.

“They won’t need to come [to court] again. So they can get on with their lives, and it just takes a lot of the pressure off them,” Prof Cashmore said.

Similar schemes are currently being trialled – or are in place – statewide in Tasmania, the ACT, and South Australia; and in limited jurisdictions in Queensland and Victoria.

Glowing reviews

Independent assessments by the University of NSW in 2017 and 2018 found the program to be a success, reducing stress for children, resulting in a better quality of evidence, and earning “unanimous support” by stakeholders and participants.

It was as a result of these “glowing” evaluations that, in November 2018, Ms Berejiklian announced the “highly-successful” program would be made permanent.

“NSW is leading the country with this important initiative which delivers support to young victims of sexual abuse and child witnesses,” she said at the time.

Mr Speakman echoed her sentiment, noting that the scheme had proved vital in ensuring children understand and are understood during the court process.

“Going to court can be stressful and traumatic for anyone, let alone young people. This program ensures that some of the most vulnerable people who come in contact with the justice system get the support they need,” he added.

Four years on, the program continues to provide, as the Attorney-General said, child survivors with “the support they need”. But it’s a level of support that is still only offered to those who reside in the Newcastle and Sydney LGAs – despite the NSW Government’s vow to expand the scheme, nothing has been done.

This disparity of access is something Rose and Pippa find particularly unfair. They are demanding the program be made accessible to any child in the state who has reported sexual abuse.

The girls’ mum, Michelle Milthorpe, says it is “absolutely a double standard” that the program hasn’t been rolled out across NSW.

“It’s not fair for country kids, or for any child. There’s children in Sydney that don’t have access to this,” Michelle, who first urged the NSW Attorney-General (then Gabrielle Upton) to consider expanding the program in 2016 following her daughters’ trial.

“It’s not fair that children are not treated equally in this, because they have already been through the worst experience. They should not be re-traumatised by the legal system.”