‘Peace of mind’: Bailed domestic violence offenders to wear ankle bracelets in NSW

Alleged serious domestic violence offenders will be required to wear an ankle bracelet from today in a significant NSW bail law reform.

Alleged perpetrators of serious domestic violence offences will be required to wear an electronic ankle bracelet from today in a significant reform to NSW bail laws.

Under the major crackdown, alleged offenders who are granted bail will be monitored around the clock by Corrective Services using GPS technology.

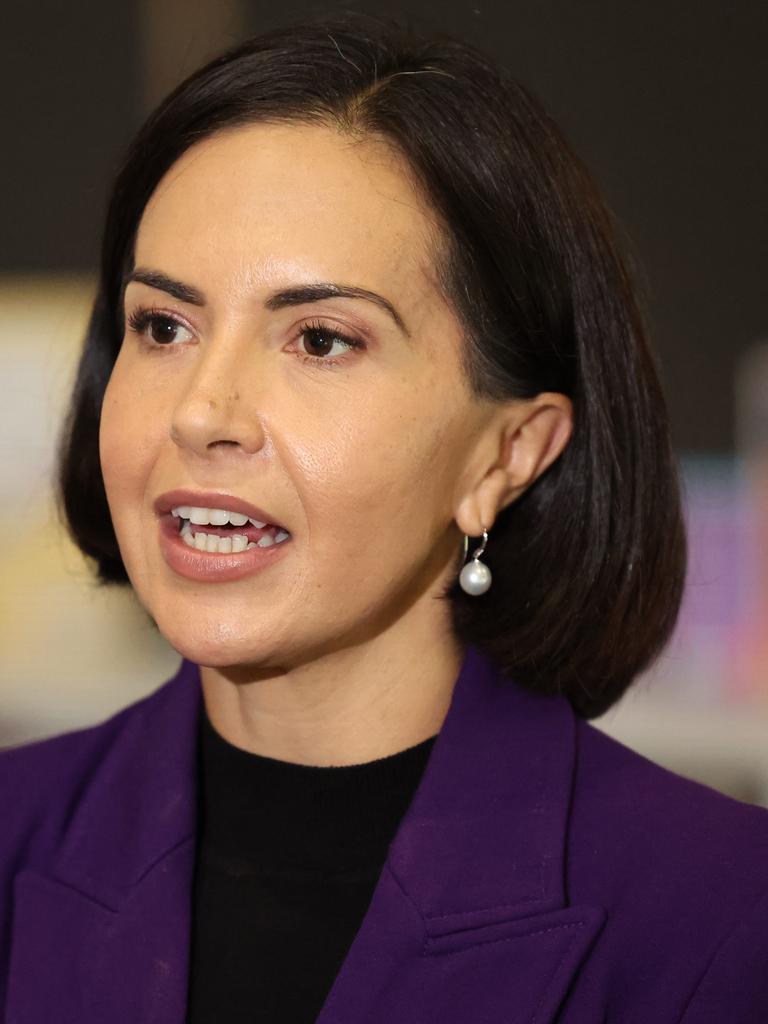

“It’s harder now for alleged domestic violence offenders to get bail, but if they do, these new monitoring devices ensure corrective services will be able to keep an eye on their movements,” NSW Deputy Premier Prue Car said on Thursday.

If an alleged offender enters a zone restricted under their bail conditions – which could include locations where people in need of protection live, work or frequent – a Corrective Services monitoring officer will immediately be notified, and NSW Police alerted to a potential breach.

NSW Women’s Safety Commissioner, Hannah Tonkin, said the changes “will give victim-survivors of domestic and family violence greater peace of mind and support their safety planning while the matter is dealt with in the courts”.

The NSW Government previously reversed the presumption of bail for alleged serious perpetrators – meaning they needed to explain why they should be released from prison if they’d been charged with any of several serious domestic violence offences.

“Serious” domestic violence offences are those committed by an intimate partner that carry a maximum jail sentence of 14 years or more, and include sexual assault, kidnapping, coercive control (criminalised on July 1) and strangulation with intent to commit further offence.

Premier Chris Minns launched a review of the state’s bail conditions for alleged domestic and family violence offenders in the wake of Forbes mum Molly Ticehurst’s death earlier this year.

The 28-year-old was allegedly murdered by her ex-partner, Daniel Billings, on April 22.

Fifteen days prior, Billings had been released on bail, charged with a raft of sexual and domestic violence offences against Ms Ticehurst, including allegations that he’d raped her three times. An interim apprehended domestic violence order had also been made banning the 29-year-old from contacting Ms Ticehurst, going within one kilometre of her home, work and other places.

Electronic monitoring of alleged perpetrators was among the measures Ms Ticehurst’s family called for following her death.

“There has to be something put in place that says if you receive bail today, we will know where you are the minute you walk out of there,” spokesperson for the family, Jacinda Acheson, told the ABC in May.

“The monitoring devices need to be put in place and it needs to become Molly’s Law.

“Molly did everything that she could and, when she finally became brave enough, and let’s make that abundantly clear that Molly was brave, very, very brave and courageous, to ask for help, the help was not given.

“The judicial system let Molly down; the victim support teams let Molly down.

“In Molly’s case the police did everything they could to keep Molly safe.”

Data from the Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research showed the number of adults in custody for serious domestic violence offences is at an all-time high of 3008, with over half on remand.

NSW Minister for Women, Jodie Harrison, said the introduction of electronic monitoring placed an emphasis on the importance of victim-survivors’ safety.

“This is one part of a co-ordinated, multi-pronged response to addressing domestic and family violence in our state that includes earlier intervention and primary prevention,” she said.

While Attorney-General Michael Daley described domestic violence as “an abhorrent crime and one that the NSW government will not tolerate”.