Opinion: Strikingly similar excuses from rapist and university aren’t good enough

THE outrageous excuses used by these “clean-cut” rapists might sound familiar, because they’re not the only ones using them.

OPINION

WARNING: Graphic content

THEY are wolves in sheep’s clothing: rapists who present to the outside world as clean-cut and harmless, and who are all the more dangerous for it.

Men like Brock Turner, the “Stanford rapist”, who served just three months behind bars after sexually assaulting a passed out woman behind an alleyway dumpster.

Or Douglas Steele, the James Cook University (JCU) employee and father of three, who will now serve just four months in jail for digitally raping a twenty-year-old indigenous student in September 2015.

Like Turner, the disparity between Steele’s crime, and his outward image could not be more glaring.

On Tinder he promotes himself as a family man with an interest in “feminism”, “coffee” and “intellectual discussions” with “new friends”. But on the night of the rape, he entered a bedroom under the pretence of assisting a barely conscious student, and once alone with his victim, he raped her.

Much has already been written on “nice guy rapists”: Perpetrators who are able to assault their victims by gaining access and trust, often through behaving in charming, non-threatening ways which lower a victim’s defences.

But what is also disturbing in this case is that, like Steele, the university has presented one smiling face to the public, while behaving very differently in private.

Not only did JCU promote Steele after he had been charged with the rape, but they also appointed him academic adviser in the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Centre. Steele remained in this role even after he pleaded guilty to the rape, and was further supplied a glowing character reference by a staff member at the university

Having spent two weeks covering this case, what is both fascinating and disturbing to see is how the tactics, strategies and excuses used by JCU neatly mirror the tactics, strategies and excuses employed by the rapist himself following the assault.

Indeed, having been accidentally copied in on highly confidential correspondence from JCU discussing their damage control strategy, there is an important case study here on what not to do when responding to a media crisis.

TACTIC ONE: MINIMISE THE SITUATION AND DOWNPLAY RESPONSIBILITY

“I only put one finger in, I didn’t think she would know because she was so drunk.”

“I only put my finger in and she was already wet.”

According to police documents tendered to the court, these are two of the excuses that Douglas Steele used to minimise and defend his actions.

Karen Willis, Executive Officer of Rape and Domestic Violence Services Australia says that “some offenders minimise their crimes to justify their actions to themselves, but most are just trying to get away with it through excuses which play into the many myths in society about sexual assault.”

Interestingly, in their first statement to the press on the Steele matter, JCU also adopted a similar tactic, minimising their responsibility and involvement. They claimed the rape was a “police” matter that had “been dealt with through the criminal justice system” and that “the charges in this case did not relate to the defendant’s role at JCU, or any events on campus.”

This is a classic distancing technique: by refocusing the attention on where the rape occurred (as opposed to why JCU continued to employ a known rapist) JCU is diverting attention away from their own internal failings, while also attempting to disassociate themselves and their brand from the rape and the rapist.

TACTIC TWO: REFRAME WHAT HAPPENED

“The more I think about it, my finger just slipped in while I was moving her into the recovery position.”

According to police witness documents, at one point Steele attempted to reframe the rape as him helping the victim. This blatant attempt to rewrite history and reinterpret events is highly disturbing.

Yet in a statement put out by JCU, the University also adopted a similar strategy to spin events and reinterpret facts in a way that cast their actions in a more positive light. They said “when the University became aware of this matter, steps were taken immediately to ensure the student felt safe on campus. Her welfare and privacy have been, and continue to be, our primary concerns.”

Except, not only did the victim drop out of her studies, but her rapist was permitted to remain working there — and was even promoted to work directly with indigenous students.

An indigenous academic affiliated with the university has also challenged JCU, saying, “there has been a lot of support for the victim, but that was not given from the university. It was given from an indigenous way of working. People who have protected her, those who know her, have formed a circle of support.”

TACTIC THREE: BLAME SOMEONE ELSE

In the days following the rape, Steele allegedly blamed his ex-partner for the rape and threatened suicide in order to get her to meet him. According to her police statement he called her saying “I’m at the top of Mount Stuart and going to throw myself off”.

When she refused to meet him there, he then told her that “none of this would have happened” if she “had gone over to watch the Cowboys game [with them on the night of the rape]”.

According to the witness statement, Steele also bemoaned how the rape would affect his future, and his custody of the kids: “I don’t know what to do. I’m worried about my future and not seeing the kids” he reportedly said.

Willis says that manipulating a person’s sympathies, threatening suicide, playing the victim, and pointing the finger at someone else, are all tactics used to “shift blame” and avoid accountability.

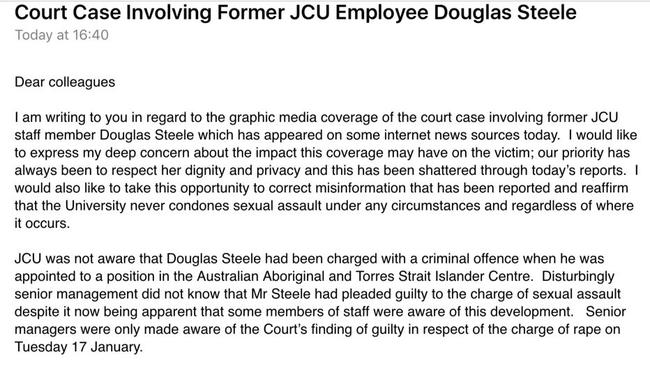

Following the first round of media reports on the matter, JCU also sent out a letter to all staff, pointing the finger at the media and blaming us, as opposed to the rapist, for “shattering” the victim’s “dignity and privacy”.

The letter also expresses “deep concern about the impact this coverage may have on the victim”. It did not express any “deep concern” regarding the impact of rape, or the impact of institutional betrayal.

TACTIC FOUR: COVER UP

Following the rape, Steele allegedly suggested to his ex-partner that they offer the victim “an amount of money to make it go away”. (According to her statement, she was shocked by this and advised him not to do it).

Initially when news.com.au and other media approached JCU for comment, they also attempted to cover-up their responsibility in promoting Steele and continuing to hire him, emphatically denying that Senior Management had any knowledge of Steele’s guilty plea.

On Facebook they went one step further, saying had Senior Management known of the guilty plea, Steele “would have been immediately dismissed by the University”.

But as news.com.au later uncovered, Senior Management had been informed of the charges against Steele, and were also informed of the guilty plea late last year (Steele pleaded guilty in September 2016).

A spokesman for JCU has now admitted that “I now know of individuals who were party to that information but how many and exactly who is a matter I think is best left to the investigators”.

TACTIC FIVE: MITIGATE THE DAMAGE

In September last year, Steele pleaded guilty to the rape. By pleading guilty to the offence he receives an automatic reduction in jail time.

JCU has now — through sustained media pressure — been forced to admit wrongdoing. While their initial response was defensiveness, they have now issued a statement saying:

“JCU accepts full responsibility for serious mistakes that have been made in the handling of the Steele case. The University understands the community’s anger over this matter, and apologises unreservedly for how it has been handled.”

Despite their initial position stating that it was a police matter, the university has now also ordered a full review of their own handling of the case.

WHAT SHOULD THE UNIVERSITY DO?

A FOI investigation has shown that in the last five years there have been 9 official reports to the university involving sexual assault and harassment — including an attempted gang rape — but not one has resulted in serious punishment such as suspension or expulsion.

Given this systemic problem, it’s important that JCU review their whole culture: not just the Steele matter.

Otherwise, the review can easily turn into a witch-hunt where one or two staff members are set up as fall-guys. After they are fired, the institution can then return to business as normal, claiming that they have lanced the boil, and cut the cancer out. Then the next time an incident gains media attention, the crisis management team simply dusts off the same old press statements, recycling the same empty platitudes saying “we take this issue very seriously”, without having ever done any meaningful reform.

This means involving external experts who have detailed understanding of cultural change. For example, in 2004, when the NRL was in the media following sexual assault allegations at Coffs Harbor, the NRL didn’t simply hire investigators to look at that one incident: instead they hired a team of experts at Sydney University, led by Professor Catharine Lumby, to map the whole culture of the NRL and develop appropriate cultural change interventions.

Lumby and her team conducted over 200 interviews with players, coaches, player managers and women associated with the game. They developed a detailed snapshot of the culture and subsequently brought in the NSW Rape Crisis Centre to develop a specially tailored education program which is now delivered to players.

SUPPORT THE VICTIMS

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, the university will need to support victims. And I don’t mean a cup of tea and a couple of Tim-Tams type of support. I mean practical, real world — and yes, financial — support.

The public can play a role here too, in standing with survivors by holding all universities to account. After all, it shouldn’t be on the backs of victims alone to advocate for reform and hold institutions responsible.

Indeed it shouldn’t be left to an already marginalised indigenous rape victim to have to become a champion for change. When we leave it to those who have the least spare capacity, resources, and access to platforms and power, we guarantee that change will not occur.

The public is already outraged on behalf of this victim.

But to other survivors we must also say:

We hear you. We believe you.

It’s not your fault. And you’re not alone.

We’ve got your backs.

If you or someone you know has been impacted by sexual assault support is available by calling 1800 RESPECT and asking to speak to a trauma counsellor.

Nina Funnell is an author, journalist and advocate against sexual assault. Nina has previously served on the NSW Premier’s Council on Preventing Violence Against Women and the board of the NSW Rape Crisis Centre.