‘My mother died in vain’: Naomi Lennon’s pain as her horrific childhood trauma plays out every single week in Australia

The murder in broad daylight of a Sydney mother by her abusive husband was meant to be a turning point for Australia. Her daughter is shocked it wasn’t.

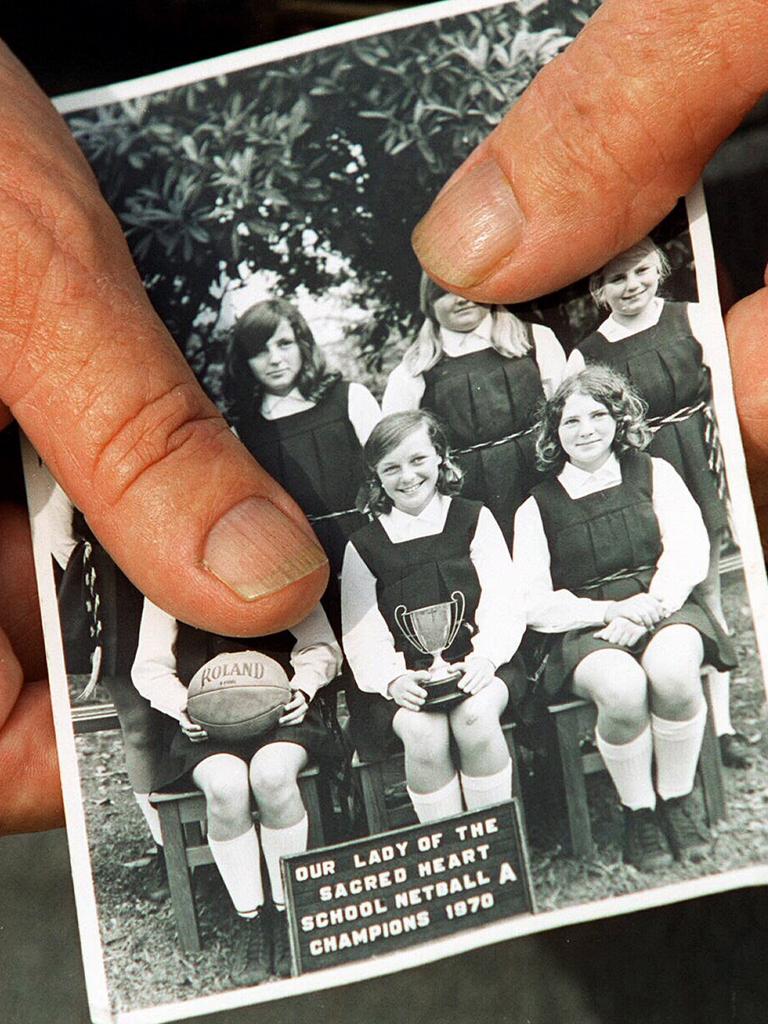

The senseless murder of Jean Lennon in broad daylight, on the steps of the Parramatta Family Court at the hands of her estranged abusive husband, was a watershed moment.

A generation of women, united in grief and fury, took to the streets in cities and towns across Australia, demanding an end to the deadly secrecy shrouding domestic violence.

Anger and mounting political pressure gave way to legislative reform, with promises that women being killed by their partners would not be tolerated, and that change had come. Finally.

That was in 1996.

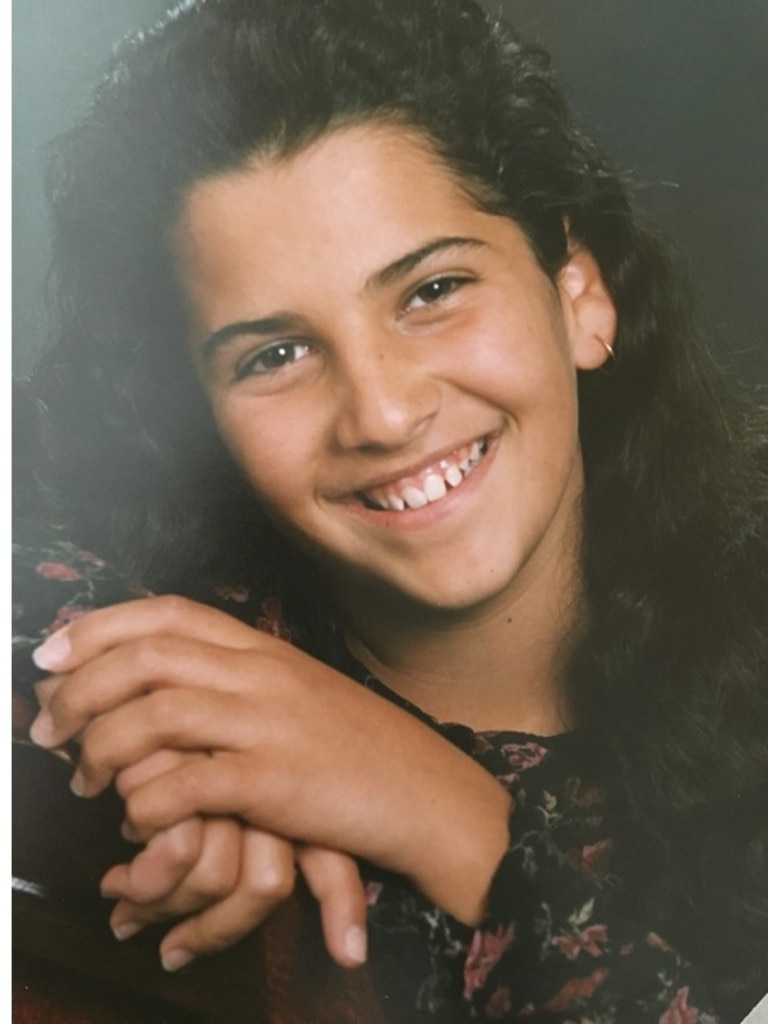

Almost three decades on, Ms Lennon’s daughter Naomi finds herself wondering exactly what has changed.

Each week, when the news inevitably comes that another woman somewhere in Australia has been killed by her partner, Naomi is reminded of the preventable and horrific tragedy she endured as a child.

Her mum’s desperation to escape harm with her four young children. The uncertain and terrifying year they spent jumping from safe house to safe house, constantly forced to flee again when he tracked them down.

And then, on the morning of March 21, 1996, when she was just 13 years old, the arrival of two policemen at the door of a suburban women’s refuge.

“I can’t believe women are still dying,” Naomi told news.com.au. “One a week. My mother’s death should have been a wake up call.”

After some 20 years living abroad, Naomi recently returned home to Australia, unaware of just how little progress had been made.

“I was told in the years after that my mother’s murder was a landmark case. It’s in legal textbooks, it has been referenced in parliament. I think I thought things would really change,” she said.

“Until I spoke to advocates like Michelle Faye, who I stumbled upon online, I didn’t not know that Australia was still stuck in this awful pattern. I’m shocked. It’s just so wrong.”

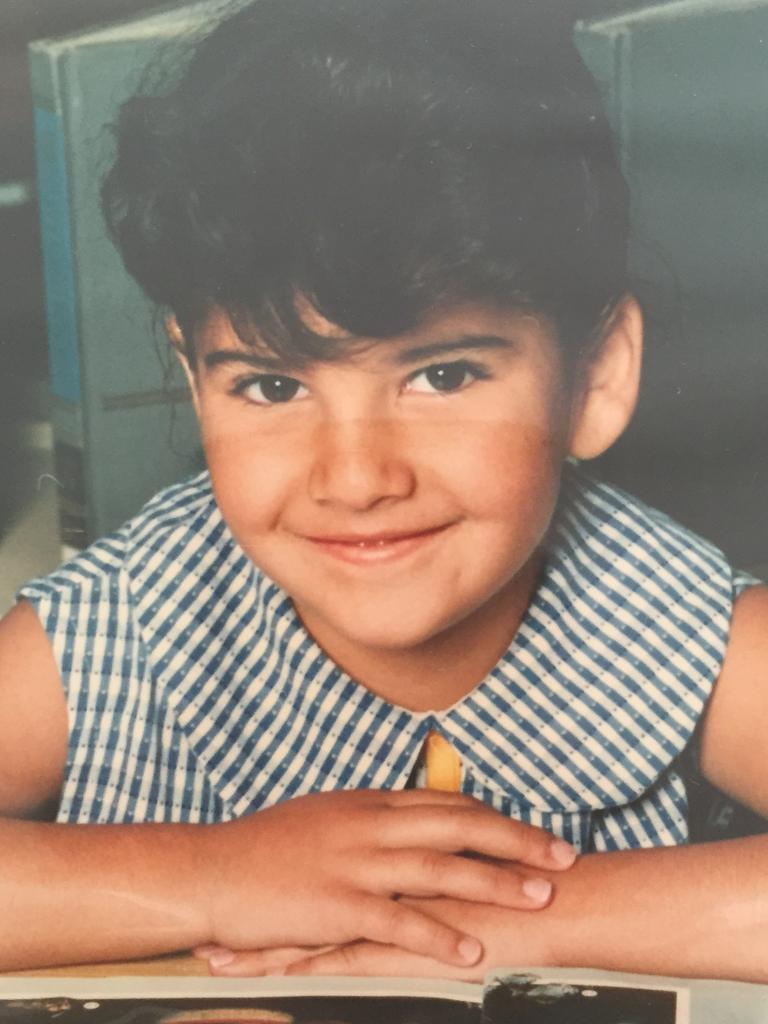

The loss of her mother in such unspeakable circumstances, and when she was at such a tender age, split Naomi’s life in two – before her murder, and after it.

Before, even though Naomi knew “there was something wrong with my father” and she feared him, her mum shielded the children from as much of the pain as she could.

“My mother really loved being a mum,” she recalled. “She was very devoted and involved. We did a lot of after school activities and always had a house full of neighbourhood children playing and having fun.

“Although this awful stuff was happening, she tried to keep us happy. Even her closest friends did not know what she was going through.”

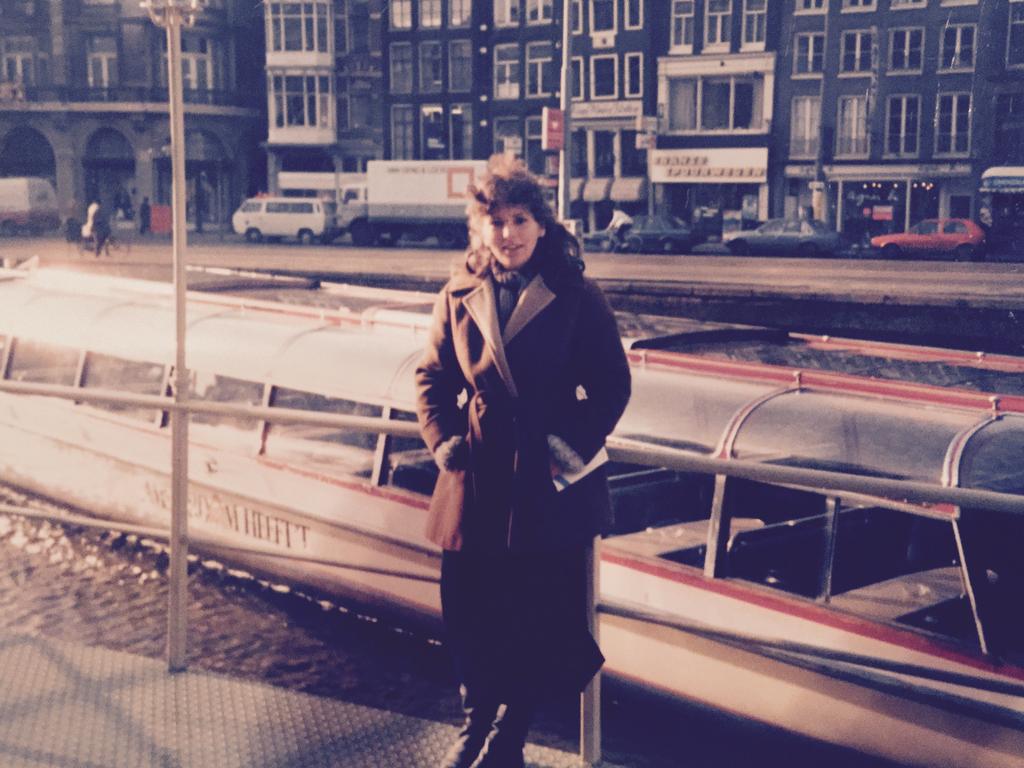

Aside from being a wonderful mother, Naomi remembers a woman who was kind, giving and warm.

“She was always helping someone with their paperwork and volunteering at the school tuckshop, where she was known to give ice creams and food away to kids who didn’t have any money and then pay for it herself,” she said.

“She loved to laugh, especially while watching Seinfeld. I can still hear her roaring laughter. She tried to give us the best childhood possible in very difficult circumstances.”

Her mum was a buffer of sorts from the realities of their seemingly picture-perfect life.

While Ms Lennon was a stay-at-home mum, her entrepreneurial spirit and business smarts meant she helped build the family’s company.

Success and wealth followed, but everything was in her husband’s name, leaving her trapped in the home with nowhere to go.

By 1995, Ms Lennon had had enough.

When Naomi came home from school one day, her mum was waiting for her with bags packed.

“She didn’t need to explain. Her face said it all. I just wasn’t aware how bad it was. I wondered when I might be able to go back to school.”

Ms Lennon and the kids packed up the car and drove to a refuge – the first of some 10 women’s shelters in Sydney, Brisbane, Perth and Canberra that the five would flee to.

“He always managed to find us,” Naomi recalled.

Despite clear stalking and intimidation, and the granting of multiple protection orders, he wouldn’t back down.

Ms Lennon was determined to fight to keep her kids safe.

“I had some visitations with him for a while, but I didn’t want to be there,” Naomi said.

“The last time I saw him, I remember being fearful. He was having a psychotic episode and I felt in danger. Afterwards, I asked mum if I could stop seeing him, so she pushed for a custody hearing.”

Ms Lennon arrived at the Parramatta Family Court early that morning, accompanied by a support worker from the refuge.

Hoss Majdawlawi walked up the steps, armed with a gun he illegally purchased a week prior, and as Ms Lennon ran screaming, he opened fire.

Naomi doesn’t recall much of the media storm that surrounded her mother’s death and the groundswell of activism it sparked.

“I think I went into a state of shock,” she said.

“I remember the doctor had to tell me several times that she had died, because my young brain just couldn’t accept it. It was horrific.”

Her maternal grandparents rushed to Sydney on the day of the murder, scooped up the kids, and took them back to Canberra.

There, surrounded by a tight-knit and protective community, Naomi was largely sheltered from the swirling discussion surrounding domestic violence.

She was spared the empty promises of change from politicians. After high school, almost as soon as she could, Naomi took off – first to London, and then to Los Angeles.

It was in the latter that she built a formidable career as a lauded talent agent, celebrated as a founding figure in the birth of social media stars.

“As a child, I always talked about America and LA and about wanting to go there someway,” Naomi said. “My mother encouraged that. After she passed, I guess I wanted to almost live the best life I could for her.

Ms Lennon was 37 when she died.

“I’m now older than my mother was when she passed, which has changed a lot of my perspective on things.”

Had the system functioned as it was meant to – as Ms Lennon was assured it would – then Naomi wouldn’t have reached that grim milestone.

Majdawlawi had been the subject of apprehended violence orders, which forbid him from contacting, harassing or threatening Ms Lennon.

They were regularly breached but he faced no consequences. It seemed as though the more he got away with, the more empowered he felt to terrorise his ex-wife.

Those orders were supposed to protect Ms Lennon and her children, but they weren’t worth the paper they were written on.

Naomi is dismayed to see those same systemic flaws still exist all these years on.

“When the system upholds AVOs we know that it saves lives. Even in less extreme cases, a credible threat of jail can change someone’s path, but right now there are no deterrents at all,” she said.

“When I would tell people my story in America, they were shocked. They couldn’t believe that breaching and AVO didn’t see my father go to jail. That’s what happens there – you breach, you go to jail until you get a court date.

“He broke his AVO five times, at least, and got out within hours. He was very violent. We were living in safe houses. That should have meant something. None of it seemed to matter.”

After he was arrested and charged, Majdawlawi pleaded not guilty. He wasn’t disputing he had pulled the trigger five times, but that he was provoked by the custody dispute.

It took a jury less than four hours of deliberation to return with a guilty verdict.

As the acting New South Wales Supreme Court Justice Hubert Bell put it in his blistering sentencing remarks: “He stood to gain absolutely nothing by the killing, except perhaps some perverse satisfaction.”

“I felt like an orphan,” Naomi said.

“To not have parents when you’re a teenager is difficult. To not have a mum to share special life moments with, whether personal or career-related, is painful.”

Despite the horrific murder, its devastating and lifelong consequences for four innocent children, and the uncontainable public rage, Majdawlawi was sentenced to just 14 years in prison.

He was released in 2011.

There’s perhaps a hopeful temptation to put that arguably inadequate sentence down to the era – a less-informed time when domestic violence was still an uncomfortable and taboo topic.

But if that were true – if the legal value of a woman’s life had risen in almost 30 years to a level even close to reasonable, then Naomi wouldn’t find herself thrust back in time to 1996.

Ever. Single. Week.

“Something has to change and stricter punishments for breaking AVOs is an essential step,” Naomi said.

“We need a no-tolerance policy or people will continue to die. Australia is known to punish the smallest offences in what’s often called a ‘nanny state’, but if you are a repeat offender of a serious AVO breach, you are free to go.

“I believe change is easy to implement and the impact will be immeasurable. I know this better than anyone.

“Losing a parent so young, so unnecessarily, has been tough. I would do anything to help others and I feel my mother would want me to be this advocate as well. So, that’s what is pushing me to do what I can now.”

Read related topics:Sydney