Mia Ayliffe-Chung’s mother Rosie issues final plea for change in heartbreaking new book

The mother of murdered backpacker Mia Ayliffe-Chung has called on Australia to act as she reveals the full story of her daughter’s tragic death.

In her seminal book on grieving, My Year of Magical Thinking, Joan Didion details the disorienting experience of secretly believing her dead husband could walk through the door at any minute.

Rosie Ayliffe, mother of murdered British backpacker Mia Ayliffe-Chung, had similar thoughts after her daughter was killed at 20 years old in a Queensland backpacker’s hostel in August 2016.

As television crews swarmed her village in England’s East Midlands after the devastating news emerged, Rosie recalls opening her laptop to look for messages from Mia, and imagining her going outside to chat to the press with mugs of coffee.

“It wasn’t that I didn’t know she was dead, or that I didn’t know she wouldn’t come home, but it was a truth of such earth-shattering magnitude that I couldn’t accept it,” Rosie writes in her heartbreaking new book, Far from Home: A true story of death, loss and a mother’s courage.

RELATED: Mum’s agonising discovery after daughter’s murder

Mia was completing her 88 days’ farm work to obtain a 417 visa for a second year in Australia when she was fatally stabbed at Home Hill hostel by 29-year-old Frenchman Smail Ayad, who then killed backpacker Tom Jackson as he tried to protect her.

“The loss has been a long ache, and many many nights I lie awake, thinking about my daughter’s last moments, and how it must have felt for her to lie dying,” Rosie told Ayad’s hearing at Queensland’a Mental Health Court in April 2018. “Did she feel pain? Did she know where she was going? The images haunt me, waking and sleeping.”

After the tragedy, Rosie travelled to Australia to retrieve Mia’s body and began hearing stories about widespread financial and sexual exploitation and psychological abuse on farms where young people were working, and an astonishing lack of regulation or oversight.

It marked the start of her tireless, five-year campaign to change the farm work system that she believes contributed to her daughter’s death — one she believes is now in Australia’s hands.

“This is the end of the road as far as I’m concerned,” she tells news.com.au. “The book is a call to arms and an expose and if that isn’t enough, then what is? What else can I do?

‘I JUST NEEDED TO KNOW’

After her world fell apart, the former Rough Guide travel writer turned English teacher channelled her grief into learning more about the farm work scheme and launching a campaign to protect backpackers as well as migrant seasonal workers she discovered faced many of the same issues.

Unable to bear returning to the classroom, she set up a website and Facebook group for travellers to share their experiences, building a list of hostels and farms to avoid.

RELATED: Murdered backpacker’s troubling Facebook message to mum

I interviewed Rosie shortly after Mia’s death, and met her in Sydney while she was working on an Australian Story documentary to bring attention to the cause. Thanks to her indefatigable campaigning, numerous backpackers came forward and shared appalling stories with news.com.au and other outlets — of employers taking away passports; travellers kept in debt bondage; underpayment or no payment; dangerous conditions; and even rape and physical assault with few consequences for the perpetrators.

Speaking to me from her Derbyshire home, Rosie says this book marks her final appeal to Australia to do the right thing.

“It’s an Australian problem; for me to stay involved, it’s almost as if I’m filling the gap and making things easier, because if I’m rescuing people in the limited way that I’ve been able to from the UK, then it’s almost as if, ‘oh that’s job’s being done.’”

On one of several trips to Australia, Rosie visited the Townsville hostel to piece together what happened in her daughter’s final moments, a painful experience that left her in floods of tears. She learnt the young woman was not unconscious from the first blow, as she had been led to believe, but ran for the bathroom after Ayad stabbed her in the heart, where she lay dying in the arms of another backpacker.

“I don't feel angry with anyone at all, I never did, I just needed to know,” she tells news.com.au. “I feel that I know enough now, I understand what happened and that’s all I needed.

“I don’t need revenge, I don’t need to get the hostel closed down, I don’t to go on some sort of rampage to make sure I have him locked up for the rest of his life ... I just need the truth, and everything else is down to other people. This is now the responsibility of others, to make sure this doesn’t happen again in some respects.”

Writing the book was “incredibly tough,” she says. “I spent days mopping tears off my MacBook.

“It was as tough as I thought but it was incredibly cathartic and it has been part of my journey to recovery in a way that I’d never imagined.

“I want to memorialise Mia, and our relationship, that was a big part of it — and to express how I feel about her .... also the campaign front, just to get the word out about how potentially perilous it can be for backpackers and other migrant workers in Australia.”

‘SHE WAS HOLDING THE PENCIL’

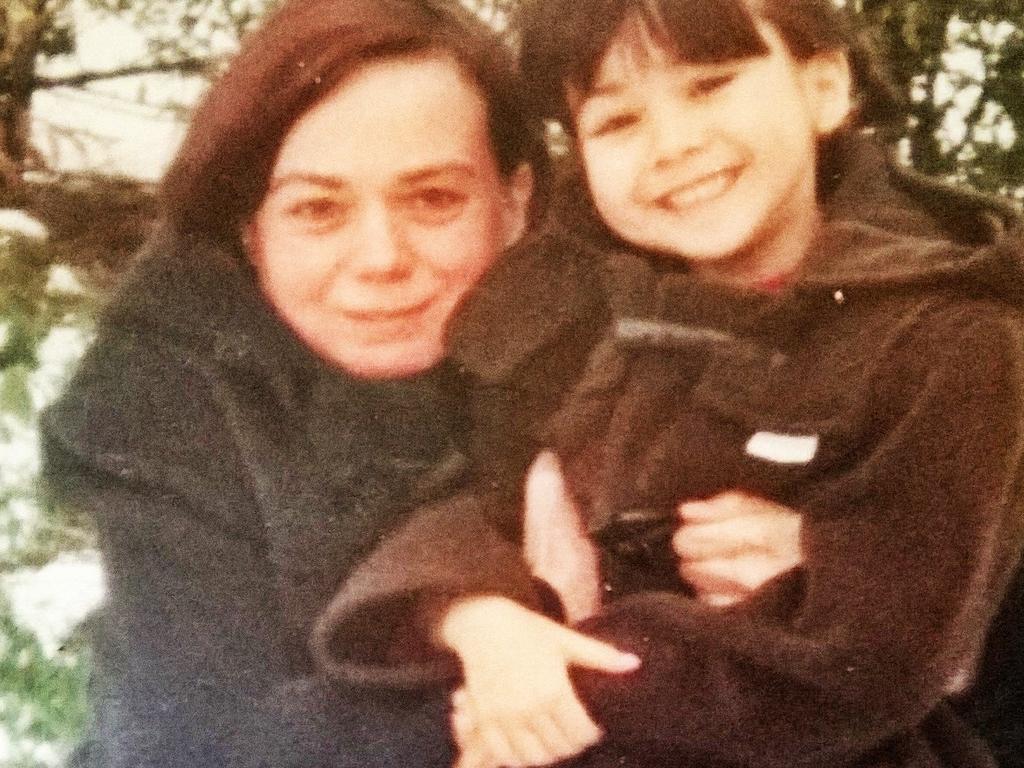

Rosie writes beautifully about her deep bond with her daughter, describing her early years as a single mother in a central London apartment “grazing poverty” but exploring the city with Mia, and taking her on travel writing trips, passing on a taste for adventure.

“For most of Mia’s twenty years, it was just Mia and me. I always felt that we were almost umbilically linked,” she writes. “I could walk into a room and, without looking up, Mia would sense something and say, ‘What’s wrong?’”

She paints a vivid portrait of her daughter as a young woman with a strong sense of justice, who hated gossip and remains her “moral compass”, guiding her through life as a “small voice of kindness and compassion” in her ear.

“I felt I did it [wrote the book] with her permission,” she tells news.com.au. “And I felt she was holding the pencil some of the time.”

The book is a poignant tribute to a vibrant young woman who loved to dance and laugh, and touched many people’s lives in the UK, Australia and across the world. Since her death, friends and fellow travellers have contacted Rosie to share “how kind Mia was, how tolerant of others, how full of love for everyone she met, how she would stop and speak to mothers in the slums of Mumbai or Essaouira and play with their children, or dance with homeless people in the city streets in the UK.”

Rosie — who married her partner Stewart in 2018 “for the community as much as for us, because they’d had a rough time” — displays the same remarkable empathy she attributes to her child.

Despite her own unfathomable loss, the book is filled with this fiercely independent mother worrying endlessly for Mia’s grieving friends, as well as the children her daughter used to babysit, as she drives across Australia meeting grassroots campaigners and the nation’s top politicians.

Rosie confesses that her indomitable spirit and brave campaigning was at times driven by the fact “I didn’t care so much whether I lived or died.”

Mia’s death made her “almost fearless” — with the hard-working activist making global headlines when she stood up to Donald Trump after he listed the attack as an example of Islamic terrorism.

Rosie had extended her home while Mia was in Australia in preparation for a childcare centre her daughter had spoken of opening. The 20-year-old had said she wanted to start having her own children in her 20s.

“The feeling, at first, was that I’d lost her and grandchildren, and I found it very difficult to, you know, follow people with grandchildren on social media or watch people’s kids’ successes,” says the bereaved mother.

“And then I thought, hang on Rosie, you’ve never been this person who was jealous of other people. You’ve got to get over this or it’s going to destroy you.”

She says she gave herself a talking-to about being “bitter” and now tries to “love and feel good for other people”, adding that she is a “strong person”.

Rosie and Stewart have travelled, and opened a mobile pizza restaurant that has done well during lockdown. “I’ve tried to live for her and do some of the things that she might have done,” says Rosie.

“Would I have rather lived my life without Mia and not suffer the loss? No way. You know, I don’t feel like that. I was really fortunate to have such a special child, such a gift.”

She says part of her wonders if this was always meant to be. “That’s almost as if I didn’t expect Mia to grow older and I did. That’s where the loss was ... but looking back you think, maybe this was it.

“The way to find happiness is not to be forever looking at life and measuring it against what you think it should be. This is the way my life is, it’s up to me to make the best of that.”

‘LOVE AND FORGIVENESS’

When Mia first arrived at Home Hill, Rosie was concerned by the lack of health and safety training regarding snakes, hot weather and manual labour.

Later, she learned that Mia had talked about wanting to change rooms and had told one of the staff that she was uncomfortable with Ayad.

As he was taken into custody, the heavy cannabis user fought and injured police officers. He refused food and medication and was kept alive through force feeding for months, believing staff were trying to kill him.

Criminal charges were dropped after the court found he was of unsound mind and he was placed in a secure psychiatric facility for ten years. But several witnesses said that he had been obsessed with Mia — accounts Rosie still wishes the judge had looked into further.

The coroner’s report noted that Mia was placed in a room with two men, one of whom was a stranger to her who had been involved in a confrontation with other guests and had said he was unwilling to share the room.

Ayad called Mia his “wife” and demonstrated a sexual interest in her when speaking to others, the coroner said. “I consider these behaviours should have caused serious concern to those who either heard or potentially observed them.”

Rosie believes hostels “should have a duty of care towards their guests”, with a “fit and proper” test and responsibility over drugs or alcohol. They should not be able to advertise heavily online to attract visitors when work is scarce or take advantage of people made vulnerable by their need to fulfil their 88 days, she adds.

There have been some successes, thanks to campaigning by Rosie and other unions, charities and MPs. Labour hire licensing schemes were introduced in several states, meaning employers must pass a fit and proper test, pay a licence and comply with workplace laws. Victoria established a public register of labour hire providers, and an authority to monitor and investigate compliance.

But states have said that federal legislation is needed to stop criminals using loopholes by operating across state borders.

Australia’s Modern Slavery Act came into effect in January 2019, recognising the need to tackle sexual slavery, orphan trafficking, debt bondage, forced labour, forced marriage, servitude and more.

Rosie says this will have no teeth without an enforcement agency to provide a reporting system for all victims of exploitation and slavery, with officers with powers of arrest working with police. She also punishments should be increased to deter potential perpetrators and manslaughter charges introduced where culpability is proven for a workplace death.

“However, the act was a significant moment, and a crucial part of Tom and Mia’s legacy,” she writes. “It means that my daughter, and the brave man who tried to save her life, did not die in vain.”

The lull created by COVID is “an opportunity for a reset”, says Rosie, although she notes that some recent stories from farms have been as bad as ever, calling the lack of will for change “disheartening”.

She supports calls by the Australian Workers’ Union and others for a royal commission into the fruit and vegetable industry — one described as “union grandstanding” by the National Farmers’ Federation.

Rosie believes that ultimately the visa system should not be linked to agricultural work as “that is what makes these people vulnerable” in taking risks they might not have otherwise taken, or getting into difficult situations because of remoteness and lack of local knowledge.

Rosie has forgiven Ayad, and even wrote a letter to his mother in 2018, saying she understood her suffering was “not dissimilar to ours” and offering to meet her.

“Whether or not people thought I was mad for being able to forgive, I didn’t care, because it was consistent with Mia’s own values since she was a little girl,” she writes. “We both believed that you can only move on in life through love and forgiveness, which was the path she tried so hard to tread herself.”

Far From Home: A true story of death, loss and a mother’s courage by Rosie Ayliffe is available from March 30 at $34.99 through Viking