‘Maybe I should’ve just stayed’: Sinister money trend crushing Aussie women fleeing domestic and family violence

Just when they thought they had escaped harm, a huge number of Australians are being subjected to long-term financial pain that’s hard to prevent.

For too many Australian women, fleeing a violent relationship doesn’t mark the end of their torment, with instances of ongoing economic abuse on the rise.

Long after separation, domestic and family violence perpetrators still have the power to inflict significant damage on victim-survivors.

Some want to take revenge on the woman who’s left them while others still crave total control and will go to great lengths to maintain it.

Christine* ended her 12-year marriage, much of it plagued by extreme violence towards her and her four children, in 2020.

Since then, she has barely received a cent from her ex-husband, refusing to pay child support, squirrelling away money and assets, and dragging out expensive court proceedings.

“He gave up all parental responsibility,” Christine said. “I’m barely getting by, trying to get him to contribute, but he’s doing everything he can to punish me and make our lives hell.”

He tried to have her and the children removed from their home and even sent a tow truck to take away her car, the sole source of transport for the family.

“He doesn’t pay the mortgage. He doesn’t pay child support. There have been court orders but he just breaches them – he doesn’t care.

“He comes into court and cries poor and then posts all over social media how he’s living the high life with loads of cash.”

‘The abuse doesn’t stop’

When she finally had the courage to end the relationship, Christine didn’t imagine that the abuse would continue for four more years – and counting.

She barely has the time or emotional capacity to heal from the trauma of years of merciless abuse when she’s worried about putting food on the table.

“I’m having to borrow money off my family to feed my children each week. I’m terrified every time a bill comes. It’s been so rough.

“Sometimes I wonder if I should’ve just stayed and copped the violence because this is hell.”

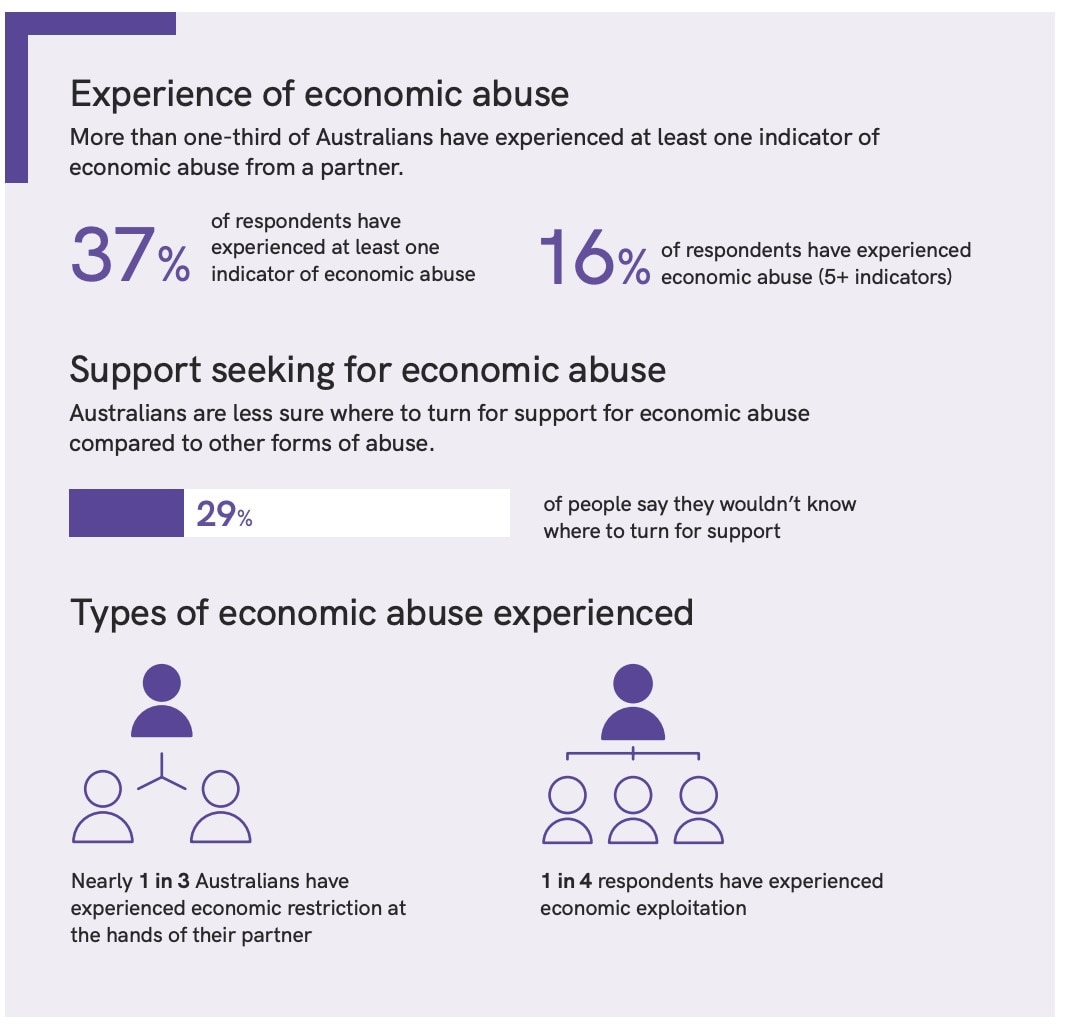

Rebecca Glenn, the founder and chief executive of the Centre for Women’s Economic Safety (CWES), said one-in-six women have experienced some form of economic abuse from a current or former partner.

“But we know that number is an underestimate, a conservative figure,” Ms Glenn said.

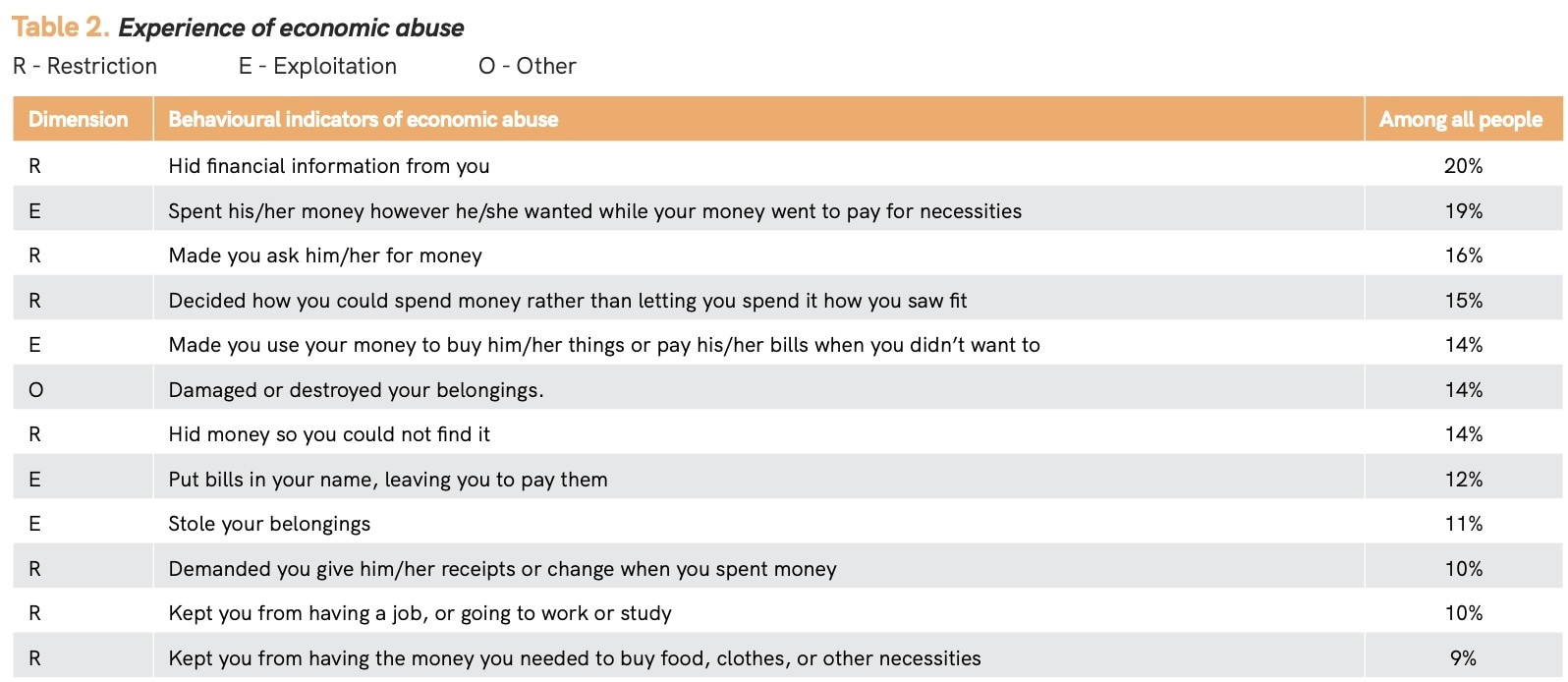

Economic abuse describes behaviours that exert control over someone’s financial resources.

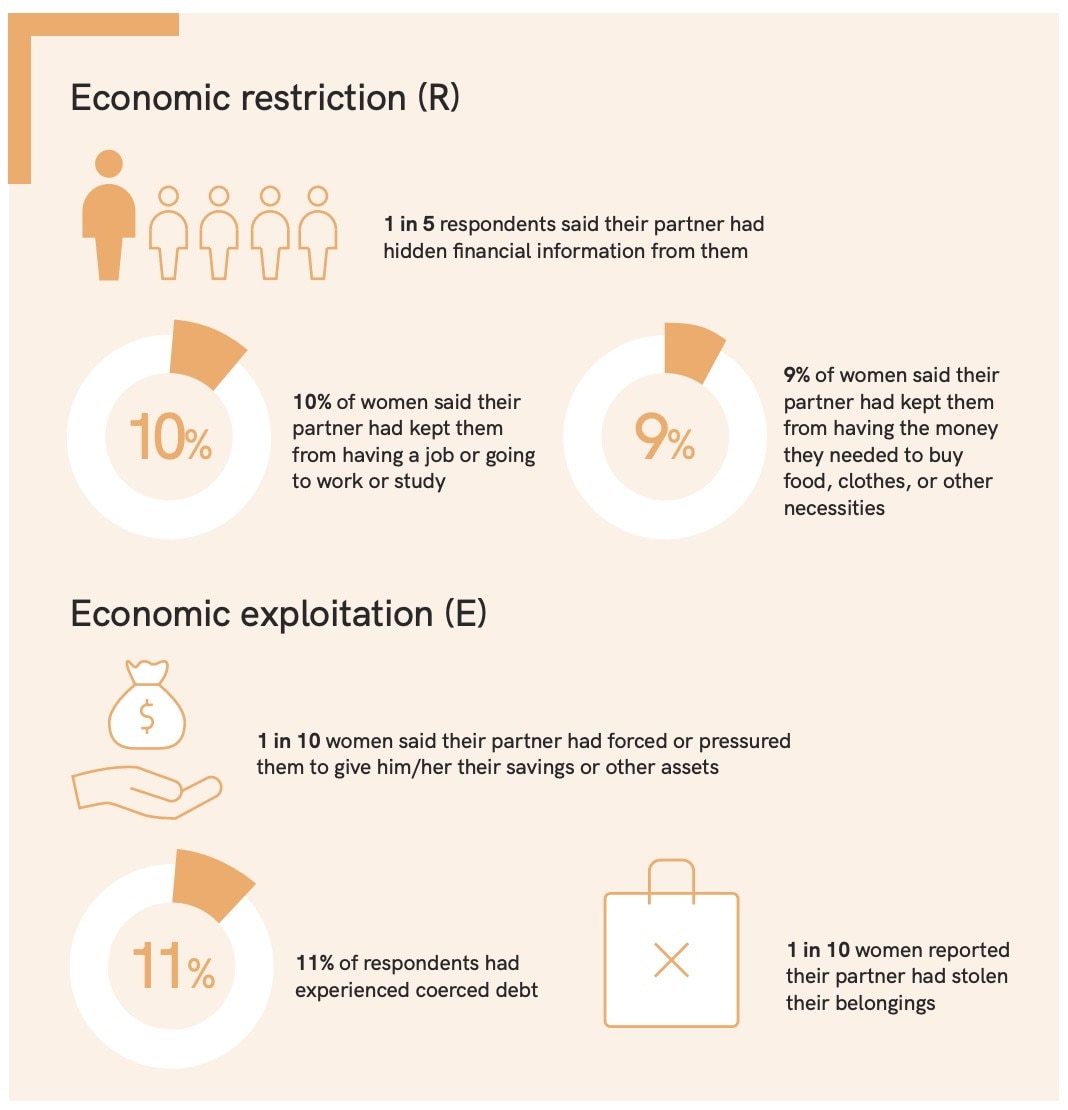

“You’ll hear of women not being able to access a bank account or being made to account for every dollar they spend on the household.

“We see impacts on financial wellbeing in the form of women not being allowed to work or having their ability to work sabotaged, such as being deprived of sleep.

“Sometimes access to transport is taken away, sometimes at the last minute, so maintaining a job is made difficult. It can be a range of things.”

When Michelle Faye was finally free from her abusive husband, she expected to get by just fine because the family company she started and ran entirely on her own was so successful.

But in reality, she was confronted with a nightmare scenario that’s still having significant impacts years later.

“When I started the business in 2007, he insisted that he set it up,” Ms Faye said. “I had no idea, but he completely cut me out of everything. It was in his name, he was the sole director, I couldn’t access the bank accounts.

“I had no control of it – totally by his design.

“When we broke up, I finally managed to wrestle control of the company. He had totally destroyed it. It was broke and severely in debt. I was left with nothing.”

Ms Faye was forced to liquidate what had been a large and growing business – one he had little to do with day-to-day, but oversaw financially.

“I have no idea where the money went. It was like the abuse was still happening, even though he was gone. He left me in a total mess.”

Various sinister tactics

Ms Glenn has worked with women who’ve had debts taken out in their name without knowing as well as survivors of domestic and family violence realising insurance policies covering them and their children have been cancelled post-separation.

“We see the non-payment of bills, such as mortgages, a lot. At separation, he’ll suddenly stop playing and leave her with the entire bill for a jointly owned property, which obviously has serious implications for her housing as well as her financial stability.”

An “incredibly common” form of economic abuse relates to child support payments, Ms Glenn said.

“We also see what’s called ‘systems abuse’, where the courts are used to inflict financial damage on women fleeing violence. Going to court is not an easy or cheap exercise, so we see proceedings initiated with the sole purpose of bleeding a woman dry.”

Some women the CWES has worked with have been forced to spend tens of thousands of dollars, sometimes hundreds of thousands of dollars, to respond to court actions.

“And that’s only people who have the means to go through the court process,” Ms Glenn added “Many people don’t.”

Missing from the conversation

In recent years, awareness about the extent of Australia’s domestic and family violence crisis has grown considerably.

But Ms Glenn is concerned that economic abuse is a major unrecognised part of the problem given it’s inflicted covertly.

“Obviously, physical violence is abhorrent. It’s great that the issue of coercive control is getting the attention it deserves. But economic abuse is missing from the conversation, and that worries me.

“In this country, we talk a lot about homelessness for older women. We talk about the face of poverty in Australia being female. We’ve seen statistics from the ABS that show us 63 per cent of women in high financial distress have a history of abuse.

“What we haven’t done is connect the dots and realised that those statistics are no accident. I’m not saying it’s the only driver, but I think economic abuse has been a very under-recognised factor in all of those outcomes we’re seeing.”

For older women who escape an abusive relationship, starting over can be an impossible task that takes an unrelenting toll, she said.

“The younger someone leaves an abusive partner to try and start again, the more chance they have of recovering and rebuilding to where they might have been.

“But the problem is the systems generally have been so unhelpful, it’s almost impossible to rebuild. The number of women on our lived experience advisory panel who have basically had to start again in their 50s, who will never get back what they had, is devastating.

“I think we’ve got to do a lot more to hold perpetrators accountable and to support women to rebuild.”

The CWES runs money clinics, providing one-to-one confidential financial counselling to support women at any stage of their domestic and family violence experience.

“They might just be a little unsure what’s going on in their relationship, or they might actually be in a domestic violence refuge thinking about their next steps, and they could realise they’ve got a whole range of financial issues some years after separation.

“And, of course, they could be continuing to experience post-separation financial abuse.”

Such is the scale of the problem that the organisation offers the services virtually anywhere in the country, and to anyone.

“One of the big problems with a lot of domestic violence services is they have really strict eligibility criteria down to geography or visa status, or assets and income tests,” Ms Glenn said.

“That means so many women in particular don’t get the support they need. We’ve worked really hard to design a service that removes a lot of those barriers.

“If you can access a phone or the internet, then we can support you from anywhere in Australia.”

* Pseudonym given for legal reasons