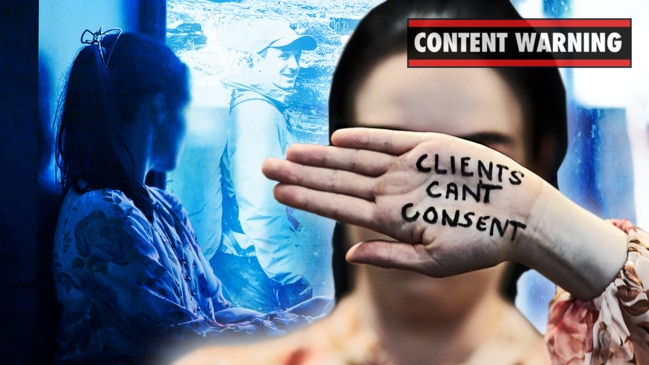

‘I was a victim of stealthing and didn’t know I’d been raped’

When journalist Ginger Gorman met a man on Tinder she thought they’d had a night of “fun”, but the reality was disturbing. WARNING: Distressing

Warning: Distressing

Have you ever really listened to the words of Neil Diamond’s song, Girl, You’ll Be a Woman Soon?

The impression is of an older man with a bad reputation, convincing a young girl to have sex with him. Hello, #MeToo.

I’ve loved and sang along to this song all my life. But suddenly, three years ago, as a 43-year-old, I began to see something more sinister. In 2020, playing the beloved song made me instantly and unexpectedly combustible with rage.

In May that same year, I was sexually assaulted. It was stealthing – this is when a person removes a condom during sexual intercourse without consent. I’ll be frank here. Until it happened to me, I’d never heard of it.

Everyone wants more details about the assault – of course they do. That’s how humans are. But as yet, I’ve never figured out how to talk about it without triggering every survivor who hears or reads my words. And there are so many survivors.

Statistics from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare claim almost two million Australian adults have experienced at least one sexual assault since the age of 15. But I know in my bones that’s a gross underrepresentation.

I know this because even after my own sexual assault, I didn’t accept it had happened. I didn’t report it; I didn’t even understand it for what it was. And I say this as someone who believes survivors. Someone who has reported their stories for more than 20 years.

There are so many reasons for my denial about what happened to me. One is because the rapes we see on TV and in the movies are violent. There’s force involved and screaming. It’s dramatic. There are police involved. Injuries. Perhaps a criminal trial.

My assault was mundane; it started with full consent and then merged into different territory. There was no force used at all.

Recently I interviewed sexual consent activist Chanel Contos for the Seriously Social podcast that I host. Chanel spoke powerfully about her own experience of sexual assault.

“I thought rapists were that stereotype of someone who is going to kidnap you and hurt you,” she said. “I didn’t realise that sexual violence can occur without physical pain being inflicted. And because I thought what happened was normal, I didn’t tell anyone. I just thought that was part of being 13.”

But I wasn’t 13 when I was raped; I was 43. A 30-year difference.

And there you have another reason for my denial. On TV – and even in the Hollywood #MeToo narratives – rape only happens to young, attractive women.

I’d spent more than 20 years avoiding this outcome. Narrowly escaping. But right at the point when my supposed “invisibility” or “unf**kability” as an ageing woman kicked in, I ended up here anyway. What a stupid myth I had imbibed to protect myself: Age will protect you from men’s entitlement to your body. It doesn’t.

Over dinner in 2020, I told a dear friend, almost in passing, what had transpired. She gently said: “You know that was rape, don’t you?”

I parked her comment; it was too hard to process. I’d just been dating after my marriage break-up. This was just a wild night.

When I had to get STI tests and the nurse, after asking me a bunch of questions, also stated: “You’ve experienced rape. Do you want to speak to someone at the Canberra Rape Crisis Centre?”

Coming from a health professional, the word “rape” was so stark and unavoidable; I blinked away tears, shocked to find them on my face.

I met him on Tinder. And thanks to research by the Australian Institute of Criminology, we already know that “ … three in every four survey respondents [have] been subjected to sexual violence facilitated via dating apps in the last five years.”

Another reason for me misunderstanding the gravity of what occurred is because when this assault happened, stealthing wasn’t illegal and the word simply wasn’t much in the public discourse. It only became a crime in the ACT, where I live, a year after my rape. It’s now illegal in NSW, Victoria and Tasmania.

The guy was ridiculously young and good-looking. As someone who’d never believed themselves to be particularly attractive to the opposite sex, the truth is that I was flattered by his attention.

Afterwards, my heart and brain desperately wanted to put this experience in the “just a bit of fun” basket. To make it OK. Even after that night, I’d wanted to see him again.

That’s right – I could never take this to the police, even if I wanted to. I wasn’t sober in the encounter. My memory is patchy. I willingly invited him to my house. I’m as far from the “perfect victim” as you can get.

You only have to read Australian author Bri Lee’s book Eggshell Skull about the Australian legal system to understand the justice system doesn’t believe women. Even consistent ones – which I, in this situation, was certainly not.

What kind of victim would want to date a man who assaulted her? As Canadian filmmaker Sarah Polley reflects in her extraordinary essay The Woman Who Stayed Silent, there are numerous factors that impact how a woman behaves after an assault.

Polley confronts the issue of why, for example, you might have friendly – or even fawning – contact with your abuser after the event.

She explains we may want to “normalise a terrible situation”. (Tick – that’s a yes from me!)

“It can seem perplexing from the outside, this pull that many women experience to make things better for those who have hurt us,” she writes.

Or speaking from my own perspective, just to make things better for ourselves.

When it comes to discussing sexual violence, I’d always heard feminists toss around the notion of the “sea of patriarchy”. As an analogy, it teetered on the edge of my understanding. We can’t see it. I’m clear on that. But what is this patriarchal sea? What’s it made from?

Here’s one example. In a complex and insightful interview with Forbes magazine in 2018 – right after the conviction of serial child molester Larry Nassar – renowned US therapist and author Terry Real told the publication: “The force of patriarchy is the water that we all swim in and we’re the fish.”

BAM! After my assault, the sea I’m swimming in became clear to me. Transparent as water, while Neil Diamond played through my smartphone in the kitchen. I could hear the sea.

The water has a lot of music in it.

It’s not just Neil Diamond. Many of the songs we grew up with in the ’50s, ’60s, ’70s and ’80s are creepy. Alongside a wider popular culture that taught women their only worth was in their bodies, the music we love preconditioned us for sexual assault, naturalised it and made it sound ‘sexy’.

Last month, I threw out a tweet. It was just a causal question about something deeply personal that was on my mind. Or so I thought.

I asked: Can you tell me which popular song lyrics you loved as a kid, but later realised they had a #metoo/creepy vibe about them?

Hi Tweeps.

— @gingergorman (@GingerGorman) April 25, 2023

I need some help w something I’m researching.

Can you tell which popular song lyrics you loved as a kid, but later realised they had a #metoo /creepy vibe about them?

For example, Neil Diamond’s "Girl, You'll Be a Woman Soon"

Thanks for your help.

Perhaps most oft mentioned in the replies is The Police’s classic, Every Breath You Take. It’s often played at weddings as a love song.

But even Sting himself said of the track in 1983: “I think it’s a nasty little song, really rather evil. It’s about jealousy and surveillance and ownership.”

The answers to my Twitter question swamped me with swathes of sinister songs about young girls being urged, coerced, and cajoled into having sex with older men.

Looked at as a collective, the propensity of predatory, violent misogynistic messages in these lyrics is staggering.

In these songs, male abusers are heroes. The girls are there to be leered at, fantasised about, lured into a bed (or a car) and frankly flattered by the attention.

There are too many songs to write about here. Let’s just say nearly every popular song I’ve ever loved is now tainted in this Twitter thread.

If we think of this as not just one Neil Diamond song, but as a sea of music that’s been the soundtrack to our lives, the question is: How do we measure how much this affects our collective psyche?

There’s an uncomfortable answer. In 2006, academics Terri M. Adams and Douglas B. Fuller wrote misogynistic music served “ … as a means to desensitise individuals to sexual harassment, exploitation, abuse, and violence toward women” and it “legitimatizes the mistreatment and degradation of women”.

I’m not a musician, but wish I were. We need new, hopeful, empowering songs for our kids to listen to – that teach consent and equality. We need to refill the water of this toxic sea.

Ginger Gorman is an award-winning social justice journalist and author.