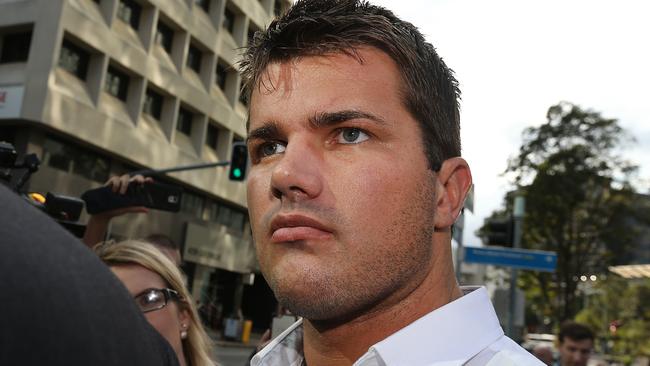

Gable Tostee’s face betrayed no hint of any nerves

GABLE Tostee kept the same expression on his face for almost his entire trial. But for one fleeting moment, he smiled.

FOR much of his nine-day trial in the Brisbane Supreme Court, Gable Tostee appeared less a man on trial for murder and more a guy casually waiting for a bus.

If the 30-year-old Gold Coaster charged with the murder of his Tinder date Warriena Wright in August, 2014, had any concerns about the potential, imminent loss of his liberty, he certainly never showed it.

Each day that he sat in the Brisbane Supreme Court dock, his face betrayed no hint of any nerves.

Tostee had pleaded not guilty and clearly genuinely believed in his innocence.

He clearly had faith the key piece of evidence at trial, the secret recording he made that captured the final hour of his date with Ms Wright, would be the means by which the jury would exonerate him.

He had good reason.

At the conclusion of the Crown’s case last Thursday, in the absence of the jury, his defence barrister — the high profile Saul Holt, QC, who represented Jill Meagher’s rapist and murderer, Adrian Bayley, pro bono in his appeals against multiple rape convictions — made a no case submission.

It could easily have seen the jury discharged and the case thrown out of court, without the need for a verdict.

Justice John Byrne is himself no stranger to high profile murder trials.

It was he who, in 2014, sentenced Gerard Baden-Clay to life in prison for the murder of his wife Allison.

Upon hearing Mr Holt’s submission, it was clear Justice Byrne agreed the murder case was tenuous.

But there were those terrified screams, apparently the key piece of evidence that could potentially convict Tostee of his Tinder date’s unlawful killing.

Justice Byrne described the Crown’s case as “weak” but also said Ms Wright’s screams in the tape were those of a person “quite clearly terrified” and ruled the ultimate decision rested with the jury.

His description of the case was one shared by Justice Debra Mullins, who bailed Tostee in September 2014.

“It strikes me that it will be a difficult case for the prosecution in relation to murder if he wasn’t on the balcony at the time,” she said.

But, it is an inherent right in our legal system that verdicts determining the guilt or innocence of charges of such a serious nature rest with a 12 person jury of our peers.

No matter what the views of the judiciary, the ultimate decision rests with them — and it is often impossible to predict what they will decide.

In the early days of his trial, Tostee was clearly buoyed by the comments of two of Queensland’s most senior judges and had every reason to appear relaxed in the dock each day.

He appeared somewhat heavier than the 28-year-old dedicated bodybuilder who was charged with Ms Wright’s murder two years ago, though his commitment to tanning has apparently not wavered.

Also apparently bearing the strain of the past two years was his significantly-aged father, Gray, who, after Ms Wright fell from the balcony, was his son’s first port of call for help.

After an unanswered phone call to his lawyer and a 3am pit-stop at Domino’s.

With his wife Helene, Gray Tostee accompanied their son to and from court each day, each day sitting in the same two seats behind the dock, where their son sat.

Showing no outward emotion, it seems, is a Tostee family trait.

In the dock, Tostee did not appear to flinch at any time.

Behind him, when the phone conversation that occurred between the accused and his father about an hour after Ms Wright’s fatal plunge, Mr and Mrs Tostee were unmoved.

When Tostee’s date was replayed through the court loudspeakers, booming lines he used on Ms Wright, such as, “Sexually, I’ll be your slave,” and telling her she couldn’t go home because she had “been a bad girl”, there was nothing.

When Ms Wright’s obviously terrified screams pierced the courtroom, there was still nothing.

The only time Tostee came close to any exhibition of emotion was when a hint of a smile crossed his lips on his sixth day at trial.

It came when his defence lawyer, Mr Holt, attacked the entity that has hounded him from the morning he walked into the Surfers Paradise police station, nine hours after Ms Wright’s death. The media.

Mr Holt claimed there had been irresponsible reporting among a number of organisations as the jury continued their deliberations.

He suggested to Justice John Byrne it could be grounds to call for the jury to be discharged, which is considered an almost catastrophic result in legal circles.

The smile came and went fleetingly.

Each day, Tostee slowly walked in and out of court, accompanied by his solicitor and his parents, not shying away from the intense media scrum he has been subjected to at each court appearance for the past two years.

Each day, he dressed almost identically: light shirt, dark pants, glasses, which he took on and off to see witnesses as they took the stand at the opposite side of the court.

Occasionally, he took notes on a notepad that sat on the bench in front of him.

Sometimes, he would turn to look briefly, as people entered and exited the courtroom.

Besides his parents, there were few supporters in court in the first few days.

But as jury deliberations continued from their first, into their second and on to their third and fourth days, Tostee, his legal team and parents holed up in a room just outside the court.

His supporter base grew with the days.

First, they were musclebound, very Gold Coast, Tostee’s comrades in the weights room, who were dressed to show off their work.

Then, there was the attractive young blonde, identity unknown, whose gasps and tears pierced the courtroom when the jury eventually cleared him of all charges on Thursday afternoon.

Perhaps, by this time, Tostee needed more than the moral support that only his parents could provide.

When the jury passed a note to the judge on Tuesday afternoon, indicating they could not reach a unanimous verdict, his guard did not drop.

But by Wednesday, there was a small, almost indistinguishable, shift in his demeanour.

Just a slight slump as he walked to and from the bathroom in full view of the media that indicated some of the wind may have been sucked from the sails of his confidence.

For the first time, he clearly had to consider that some jurors thought him guilty of the crime.

The strain of the seemingly endless wait was starting to show, albeit barely.

On Wednesday afternoon, the jury had another note.

The contents were not revealed until Justice John Byrne entered the courtroom.

Could this have been another indication the jury could not agree on a verdict?

Could he be returning to court next year, to face another jury to protest his innocence?

For four seemingly eternal minutes, Justice Byrne kept the court waiting.

The public gallery was packed but media keyboards, usually tapping, had fallen silent.

Not a word was uttered.

Tostee stared straight ahead. His mother stared at the floor.

Minute after minute ticked over on the digital clock on the wall above the witness stand until the opening of the entry door to the judicial bench shattered the quiet.

The weight of expectation hung in the air but fell, with an of expulsion of collective breath, when Justice Byrne said the jurors had another question.

By Thursday morning, nerves seemed to be starting to fray.

Mr Holt complained to Justice Byrne that jurors had been filmed as part of the daily morning media scrum that greeted Tostee’s brief walk from his solicitor’s chambers across the road to court.

It seemed a thinly veiled attempt to try to tell the media to back off. Justice Byrne dismissed it.

By late Thursday morning, the jury had finally reached the verdict some never thought would come, but it took another four hours before it was revealed.

It had only just come to the attention of Crown Prosecutor Glenn Cash that a juror had been posting to Instagram that she was deliberating in Tostee’s case.

Mr Holt made an application for a mistrial. Another few hours of legal argument ensued before, finally, Justice Byrne refused it.

Shortly after, the jury entered.

They had their verdict.

Tostee sat, as he had, for the duration of the trial, staring ahead.

More a man waiting for a bus than a verdict.

He did not look back at his parents behind him, or at the attractive blonde who seemed, post-verdict, so grateful for his freedom that she gasped and cried and gripped the hands of the person beside her.

After the designated jury spokesman finally declared him not guilty of the lesser charge of manslaughter, he clasped his hands, looked down but exhibited little emotion.

Soon after he shook the hand of his solicitor, Nick Dore.

Gable Tostee was free. As he always believed he would be.