Australia’s most shocking statistic: Sexual abuse and domestic violence against women with disabilities

IT’S the horrifying fact that no one’s talking about. Jane is one of the 90 per cent of intellectually disabled women in Australia who have been sexually abused.

ON JANE Rosengrave’s right forearm is a tattoo of a blonde-haired angel. The image looks innocent, like a little child. She holds a big, red love heart with an insignia that reads: “Free as a bird.”

This permanent ink injected under 53-year-old Jane’s skin serves as a triumphant reminder. She is a survivor.

“You only live once,” Jane says smiling and proudly holding up her decorated arm for me to see.

Jane has an intellectual disability, and over her lifetime she’s suffered unrelenting sexual and physical abuse by six different male perpetrators.

She is far from alone. On the contrary, 90 per cent of intellectually disabled women in Australia have been sexually abused. Read that again. Ninety per cent.

It’s a shocking statistic made worse by the fact that most of the abuse happens when the victims are children.

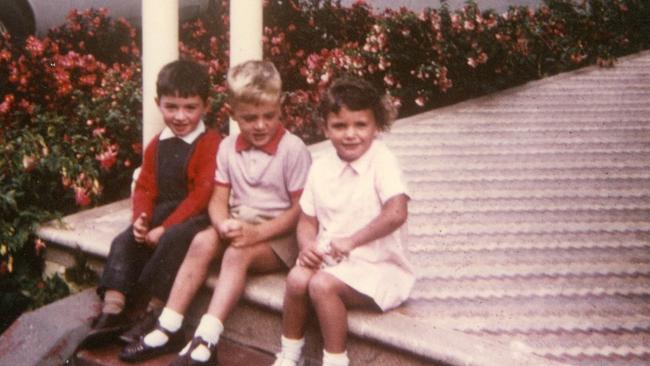

For Jane, the sexual abuse started when she was just six years old. At the time, Jane was a ward of the state living at Pleasant Creek Training Centre in the Victorian town of Stawell. The facility operated from 1937 until 1999 and housed children and young adults with intellectual disabilities.

Jane was first abused “by one of the staff members at night while all the other staff were out having a beer and drinking”.

“I was only little, I didn’t know what was right or what was wrong,” she recalls.

The abuse at the erroneously named Pleasant Creek Training Centre never ended. Another senior male staff member used to lock the door and force Jane to masturbate him or give him oral sex.

If Jane didn’t do as she was told, all children in her ward would have privileges — like going swimming in the pool — taken away.

There’s another reason Jane was “too scared” to report the abuse. Jane says that at Pleasant Creek, children who didn’t comply with instructions “used to get the strap” and “soap rubbed in your mouth” or even “get food forcibly shoved down our mouths”.

This fear is why, when Jane was sent to work at a plant nursery as a teenager and a co-worker started feeling her through her clothes and attempted to rape her, she fought off his advances but didn’t tell a soul.

“Then at the age of 16, that is when I was raped in the back of a bus … by a bus driver,” Jane says.

The sexual assault was premeditated. As the bus driver locked the vehicle away in the depot, he told her: “Lie down on the back seat, pull your pants down and wait for me and I’ll lock the front gate.”

He raped her with a condom on and after the act, dismissed her when she cried out: “I’m bleeding, why am I bleeding?”

The bus driver abused her for three years. Jane believes his wife and children knew — because sometimes she would visit their family home and need to take a bath — but no one stopped it.

Finally, Jane left the institution in the mid-1980s and moved into a supported community residential unit. Then a few years later she shifted into a privately rented flat and her then-partner — we’ll call him Patrick — moved in.

He wasn’t violent at first. But gradually, as Jane joined community support groups and learned to advocate for her rights, the verbal and physical abuse started.

“I wanted to be more independent and not depend on him and he didn’t like that,” Jane says.

She describes the long night in the winter of 2013 when she realised the relationship was over. Patrick threw household items — like pots and chairs — at her. He put her in a headlock and kept her hostage in a locked room for 24 hours.

“I never had my medication for high blood pressure and panic attacks,” Jane recalls.

Almost as a side thought, Jane explains that she had known Patrick and one of his relatives for decades. She says that before she was together with Patrick, his relative “pushed himself onto” her many times.

Although Jane doesn’t describe the unwanted sex Patrick’s relative forced on her as rape, that’s what it is. To her, it’s just another fact of life.

Three years ago Jane left her violent partner.

“Now I want the other half of my life to be free as a bird and to live on my own. I’m not interested in guys,” she says with a broad, satisfied grin.

The shocking statistic that 90 per cent of women with an intellectual disability have been subjected to sexual abuse comes from a recent Senate submission by the Australian Cross Disability Alliance.

The document is particularly scathing about violence perpetrated against people with a disabilities who live in residential care or institutions, stating that this is “Australia’s hidden shame”.

“It is an urgent, unaddressed national crisis, of epidemic proportions,” the document states.

Dr Jess Cadwallader, who works on violence prevention at People With Disability Australia assisted with researching the Senate submission.

She describes residential care as “one of the big problems” in relation to violence against women with disabilities.

“These settings are often separated off from the community, and there’s very little ordinary and everyday oversight of what’s going on within them,” Dr Cadwallader says.

Traditionally, domestic violence is thought of as something that occurs in private homes. However, Dr Cadwallader points out that residential care facilities actually are the homes of those that live there.

“We have to remember that staff members may in fact be perpetrators in these circumstances.

“You may have a woman receiving very personal, intimate care from a man who may also be a perpetrator.

“Because it’s very hard for her to report that without experiencing some form of retribution from the perpetrator, she may not raise it,” she explains.

For people with disabilities, Dr Cadwallader says domestic violence can — but doesn’t always — take a different shape to violence against those who are able-bodied.

By way of example, she explains that a disabled woman “might be denied access to medications or they might be denied access to their mobility aids, like a wheelchair or crutches”.

These actions “can prevent women with disability from even leaving the house or interacting with anyone else or can even damage their physical wellbeing”.

“We have to understand that this is an assertion of coercive control over that person,” she says.

Eloise*, 36, understands this issue with forensic intimacy. She has a degenerative disease and sometimes uses a manual wheelchair that her partner, Jordan*, has to push.

“I can’t manage it on my own, so it is up to him where I actually go with the chair.

“And I really hate it, the number of times he parks me off in a corner and walks away, and just leaves me there. It has actually become a way of controlling me,” she says.

On the day we meet, Eloise is wearing an attractive, colourful dress and has neat, stylish hair. She explains that this is a “good day” — she’s able to walk using underarm crutches. On other occasions, she is unable to get out of bed without assistance.

Thomas*, her middle child, has severe behavioural difficulties. About six months ago, Eloise recollects that he “was having a massive meltdown” and “was [lying] on the ground.”

Eloise says her partner started kicking Thomas.

“He just turned around and slammed his foot down on my son,” she says, and then “physically dragged him up the hallway into his bedroom [and] threw him in there”.

“I called the police. I told him to get out of the house,” Eloise tells me.

Not only is Jordan physically and verbally abusive to Thomas, he has hurt Eloise too.

During an argument, Jordan attempted to rape her.

“He’s a big man. He laid down on top of me and held me down and started trying to kiss and grope me,” Eloise says.

Eloise recalls “screaming at the top of my lungs” and says she “clawed him to try and get him off me”.

“I was hurt, I was bruised, I was incredibly shaken up. And I just grabbed my kids at two o’clock in the morning and drove to my parents’ house some hours away, and my parents didn’t believe me.”

According to Eloise, her parents responded by saying: “No, this couldn’t have possibly happened, he’s such a nice man. You must be exaggerating.”

Dr Cadwallader says it’s extremely common for women with a disability to have trouble being believed by those they are reporting the abuse to.

“Certain people are understood to lack credibility and may be excluded from giving evidence in court because of disability.

“Police in particular may believe that the perpetrator is such a good guy for looking after this woman with [a] disability and so won’t believe her when she says that he’s being violent towards her,” Dr Cadwallader says.

All three women interviewed for this story — and several others working in the sector that we spoke to for background information — repeatedly expressed dismay at the lack of support for women with disabilities experiencing domestic violence.

“I actually think that a lot of people in the domestic violence sector imagine that there is someone else to deal with violence against people with disability [and] that it isn’t their responsibility,” Dr Cadwallader says.

“Women with disability are not generally understood as part of their potential clients, even though they’re over-represented amongst their clients,” she adds.

Even so, Jane is hopeful of change. To this end she’s given evidence to the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse.

She encourages other women with disabilities and other indigenous women to “have a look at my story” and reach out for help.

For Eloise’s part, she did try and leave Jordan but after eight months of being separated, took him back.

“Because Jordan is listed as my partner and carer with all government agencies including Centrelink, the NDIS and the ATO, his finances directly impact what benefits I can receive,” Eloise says.

“I couldn’t get enough funds together to pay people to help support me and my children. I had no family support nearby.

“My disability is such that I struggle with day to day living tasks like shopping and showering,” she says. “I couldn’t cope.”

In the end, Eloise’s health let her down.

“I got so unwell. I couldn’t look after my children [that’s the] long and short of it.

“If I had to go into hospital, my children were going to go into foster care,” she says.

Although Jordan has had specialist counselling for domestic violence perpetrators, Eloise is still afraid.

“I walk on eggshells constantly and I’m very careful to not let my son’s behaviour trigger Jordan,” Eloise says. “I don’t sleep very well, I’m constantly on edge.”

*For safety reasons, Eloise’s name has been changed along with some identifying details.

If you or someone you know is impacted by sexual assault or family violence, call 1800 RESPECT (1800 737 732) or visit www.1800RESPECT.org.au. In an emergency, call 000.

Ginger Gorman is an award winning print and radio journalist, and a 2006 World Press Institute Fellow. To contact Ginger for similar stories email gingergormanwrites@gmail.com or follow her on twitter: @GingerGorman