‘A bloody man should do the right thing and go to church’

HOW does a pro-gay marriage, pro-Muslim immigration and pro-Pokemon man become a priest? It all started with a killer hangover.

HE WOKE with a raging hangover one Christmas Day and thought “a bloody man should do the right thing and go to church”.

Three decades on, Father Rod Bower, 54, is the one causing headaches as Australia’s most outspoken, social media savvy and incongruous priest.

His critics call him naive and implore him not to mix matters of church and state.

They say he should look after his Christian congregation on the NSW Central Coast, stay out of the Muslim debate, stop promoting interfaith relationships and shut the hell up about marriage equality.

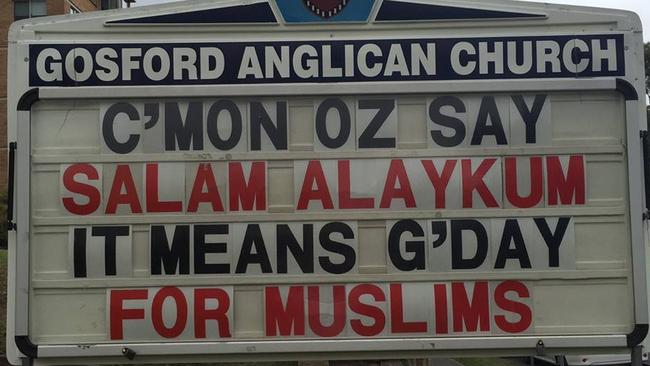

But the man behind the headline-grabbing church signs, which promote everything from gay rights to the greyhound ban, is also the man behind a the Anglican Parish of Gosford Facebook page, which has more than 42,000 likes and millions of hits.

Call it Christian (and some don’t), call it controversial, call it contrary, call it whatever you like, Father Rod doesn’t much care. He has no plans to stop creating waves.

MEET FATHER ROD

Travel to Gosford to meet the Venerable Rod Bower, Archdeacon of the Central Coast in the Anglican Diocese of Newcastle, and you quickly learn he’s not a bloke for titles.

Sure, you’ll get his views on marriage equality, refugees, climate change and politics.

You’ll also get a few tips on cleaning toilets, butchery, and a text saying “let me know when you’re at Woy Woy and I will pick you up at Gosford station”.

You wonder how to find him on the platform, so you text back: “Look for a short brunette wearing jeans, boots, yellow coat.” Then you give yourself a mental uppercut as he comes into view.

You realise the chances there’ll be more than one neatly suited bearded bloke wearing a clerical collar at Gosford station at 11am on a Wednesday are pretty remote.

His handshake is engaging, his voice calmly compelling, and within minutes you’ve heard the ready laugh, clocked his keen intellect and the sharp wit.

His left hand is adorned with a wedding ring and two band aids — a legacy of last night’s dinner preparations gone wrong.

As a former butcher, he “should know better than to take his eyes off the knife when chopping vegies”.

It’s a short drive before you catch sight of the church and THAT sign — the one that in the past few years has put Father Rod and the Gosford Anglican Church on the map.

He makes no mention of it yet, preferring to show off St Mary’s Church — a heritage-listed beauty, built in 1858, moved stone by stone in 1905 to its site, and fully restored to its former beauty, as he opens a tour of the grounds.

By the time we’ve reached the old rectory, he’s revealed himself as a keen student of liturgical architecture, and a bloke who doesn’t quite know how he ended up as a man of the cloth.

THAT SIGN

You’d like to ask first about where Father Rod’s journey began, but that sign is hard to ignore.

It has been for many since 2013, when with one impassioned message it transformed from an update of what was going on in the church and mild observations on the state of the world to a social media sensation.

Called to administer last rites to an unconscious man dying at home in Gosford, Father Rod asked a relative if there was a partner who should be present.

“It turned out he was gay, and it had been suggested his partner go into another a room while I was there,” he says.

“And I was incensed. Not at them, but at a culture that would put that family in that position that they might think I would disapprove.”

Returning to the church, Father Rod headed for the sign, and put up a message way more powerful than most mange in 50 characters: “Dear Christians. Some PPL are gay. Get over it. Love God.”

The message went viral.

“It’s now had up to 70 million hits,” Father Rod says. “The congregation weren’t really that aware of it at the time. Then the press picked it up and our Facebook page went from 150 likes to 3000 in a fortnight.”

He’s long been a social justice advocate. The Tampa affair of 2001, when the Howard government refused a boat carrying 438 rescued refugees permission to enter Australian waters, saw him passionately argue the refugee case from the pulpit, much to the consternation of some of his conservative congregation.

“I thought, OK, I have a bit of a platform here, how can I use this?” he says.

“We chose three issues to focus on: marriage equality, refugees and climate change.”

The signs became the keenly watched conduit for messages ranging from the seriously politically provocative to the humorous, with neither being mutually exclusive.

In the past few months alone, they have made ironic comparisons to the fact there’s more concern over the loss of the NSW greyhound industry than there seems to be for refugees (“If only refugees were greyhounds”). The billboard has also tackled the hot-button issues of marriage equality (“For God’s sake, just do it”); Sonia Kruger for calling to ban Muslims from Australia (“No, Sonia Kruger. Just no”), and pilloried the plebiscite on gay marriage (“Equality shouldn’t cost $160 million”).

Amid messages to Pauline Hanson (“One confused nation. Pauline, you don’t have to be part of the problem” and “Pauline, how about lunch?”) came a nod to the Pokemon Go app phenomenon (“We have Pokeballs”).

BEFORE FATHER ROD.

Rod Bowers grew up in the Hunter Valley, adopted and raised by grazier parents in Eccleston, “a place that had a school of 12 kids, two churches, a hall and a tennis court”.

It was a happy childhood.

“Dad died young but I landed in the right cradle” amid a “nominally religious” family, he says. They didn’t go to church. He went to Sunday school and had his confirmation, then didn’t go back.

When his father died when Rod was 13, he became the man of the house.

“We still had a property to run. It wasn’t others who put that expectation on me. I put it on myself,” he says.

“I was never a teenager. In some ways, I think I have always been 50, but it wasn’t until I physically turned 50 that I found myself at home in my own skin. Before that, I don’t think I ever did.”

He’s since found his biological mum and half-siblings but his biological dad died before he could meet him.

He thinks it’s common for kids who are adopted to feel like he did: “Always searching, always not really being able to be myself.”

“Part of my call to priesthood was that, but that’s only something I’ve worked out in recent times.”

His dad was a butcher before being a grazier, a tradition Rod continued. On the last day of school, he walked into a local pub, found butcher mate of his father’s and said, “Any chance of a job?”

The reply was: “See you at 6am Monday.”

THE RELUCTANT PRIEST

On Christmas Day, 1982, Rod woke at his home in Newcastle after a night on the tiles and the accompanying handover and thought, “a bloody man should do the right thing and go to church”.

“I was 20. I had plenty of money and I was living the high life in every possible manifestation of that,” he chuckles.

But he went to church and was “captured”. He went back the next week, and the next “and I just kept going back”.

“I was still living it up. I was turning up on a Sunday with a dreadful hangover but I was still turning up,” he laughs.

People started saying he ought to be a priest. To shut them up, thought he’d ask the bishop, get knocked back, and lay it to rest.

The Bishop said yes. Rod said: “Shit.”

“For me, religion was both comforting and disturbing. It was a mystery that both fascinated and terrified me,” he says. “I was drawn in and repelled at the same time. It was the mystery of whatever God is. And it still fascinates me. But I’m more comfortable with it being a mystery now than I was with it being a mystery 30 years ago.”

He started studying to be a priest and tried to sabotage it every step of the way.

“I figured they’d work out I’m a fraud and they’d throw me out,” he says.

On the day he was ordained, aged 30, in 1992, he sat supposedly deep in prayer, but in reality “counting the bricks in the wall thinking, What the bloody hell am I doing?”.

“Then I knelt before the Bishop and when he placed his hands on my head, I knew it was right. I had absolutely no doubt that that’s where I should have been,” he says.

Which doesn’t mean Father Rod hasn’t fought against the machine ever since.

THE CRITICS

He’s trolled on social media. Yes, there have been physical threats. In August, his weekly Sunday service at Gosford was interrupted by anti-Islam protesters dressed in Islamic garb in a racist stunt.

The more the social media presence grows, the more he spends time talking about Islam and speaking alongside Australia’s Muslim leaders, the louder the complaints get.

Although the ones from the congregation have died down a little.

“When I first started blasting off about Tampa, there were lots of letters to the Bishop,” Father Rd says.

“When I first began speaking out, it was a tense time, the letters to top levels of the church were flying thick and fast.

“There must be a whole room dedicated to letters complaining about me.

“These days the current bishop just sends them on to me.

“There are some people in our congregation who are challenged. There are some who have left. More have come. We offer something I guess that is unique on the Central Coast. We have a niche market.”

His refugee stance garners the most opposition and hate.

Last year, two signs — “Hell exists and it’s on Nauru” and “Hesta divests Transfield. Good on ya!”, a reference to a superannuation fund’s decision to divest its shares in detention centre operator Transfield — prompted a sea of complaints, including one from then Transfield chairwoman Diane Smith-Gander.

“She basically told my boss (Bishop of Newcastle Greg Thompson) I needed to be told to shut up,” Father Rod says.

Instead, the Bishop publicly backed him.

“Some in the congregation might tell me to shut up. My bosses never have. They’ve never told me to pull my head in,” he says.

“When those protesters invaded our service dressed as fake Muslims it was a silly stunt.

“I was annoyed for the people in the congregation, but it got more press than it deserved.

“A fortnight later when the Grand Mufti actually came and preached a sermon here — in an Anglican Church on a Sunday morning … now I think that is an event of significant consequence … that hardly rated a mention.”

He’s bagged for his dialogue with Muslims but it makes perfect sense to him.

“They are a marginalised group in our community. So I tell the story of the good Muslim — and say, ‘If you want to be part of a healthy, productive, multicultural society then you have to change the way you perceive things’. Because what we do at the moment isn’t productive. It isn’t working. It never has.”

THE MAN

In the past week, Father Rod made headlines when he spoke at a breakfast hosted by the Islamic Council of Victoria and accused Pauline Hanson of representing a “radicalised Christianity” that had no place in Australia. His real point was that the desire to protect children was the hallmark of the Christian and Muslim faiths.

Back in Gosford this week, he visited youths in juvenile detention, attended to the demands of running a region that includes 100,000 Anglicans, 10 parishes and 20 priests, did a spot of refugee advocacy, and attended graduation at school of which he is chairman.

He rises at 6.30 most days, is in bed about 11pm, and his home is his sanctuary.

He enjoys a beer in summer, a whisky in winter, a pinot noir with dinner, and his wife and he used to have “diary fights” when they first married because “I don’t have anywhere near as much time off as I should”.

He binge-watches Game of Thrones, and has grudging respect for diminutive character Tyrion Lannister. “There’s some kind of warped decency in him that I admire. He’s a politician, he’s a morally corrupt drunk and yet there’s an overarching desire to see the world a slightly better place somehow or other,” he laughs.

This year, he won the 2016 Doha International Award for Interfaith Dialogue, which recognises individuals who foster understanding between faiths and contribute to security across the world.

He travelled to Qatar to receive it and speak at the international conference.

He arrived home on a Saturday morning to preside over a wedding, discovered the cleaners hadn’t been, so did that ahead of the service.

“I have a rule that all of my priests have to be prepared to clean the toilets,” he says.

“Because it reminds us that true priesthood is about being willing to immerse yourself in the shit of life.”