Australian students falling behind: Is our education doing more harm than good?

A new report has cast a dark shadow over Australia’s school system, showing just far behind we are from the rest of the world.

The Australian science curriculum is limiting Australian students’ capabilities to learn and adequately retain knowledge.

A report by an Australian educational advisory group, Learning First, indicated that Australian students from Foundation to Year 10 are learning significantly less than their international peers.

CEO of Learning First, Dr Ben Jensen, stressed in the report the need for a curriculum reform.

“I am convinced that we cannot significantly improve their learning outcomes or reduce the increasing inequality within Australian education without a fundamental overhaul of the Australian curriculum”.

Dr Jensen told news.com.au that “a curriculum is the core of education (but) if a curriculum has holes it can contribute to a decline of other areas”.

He said that while it is normal for curriculums to change as a part of “upkeep” and refreshment, this change has shown to not be effective in the way students need.

The main difference found between the Australian curriculum and the other international curriculums is the lack of depth and build on certain topics. The report emphasised the absence of a progressive introduction to large topics and heavy content.

The report suggests the Australian sequencing of topics is skewed and lacking uniformity.

Part of the problem, according to the report, is the many “optional” topics for students to choose from. In other more thorough curriculum systems around the world, these “optional” topics are compulsary.

Learning First found that in English schools, the introduction of topics is early and continuous. Fundamental science basics, such as parts of the body, are taught as early as primary school. The report recognises that unlike Australian educators, English teachers are able to discuss various topics knowing their students have a thorough foundation of knowledge.

The report stresses that rather than realising the need for a curriculum revitalisation, educators are both directly and indirectly blamed for their students’ inability to retain the information given to them.

Dr Jensen said that there has been a history of “pointing the finger at teachers”, rather than examining other areas of cause.

He mentioned that by having a ‘high-quality’ curriculum it can “bridge the gap between advantaged and disadvantaged schools”.

Dr Jensen believes that the curriculum will “always impact teaching” but a better one will improve it.

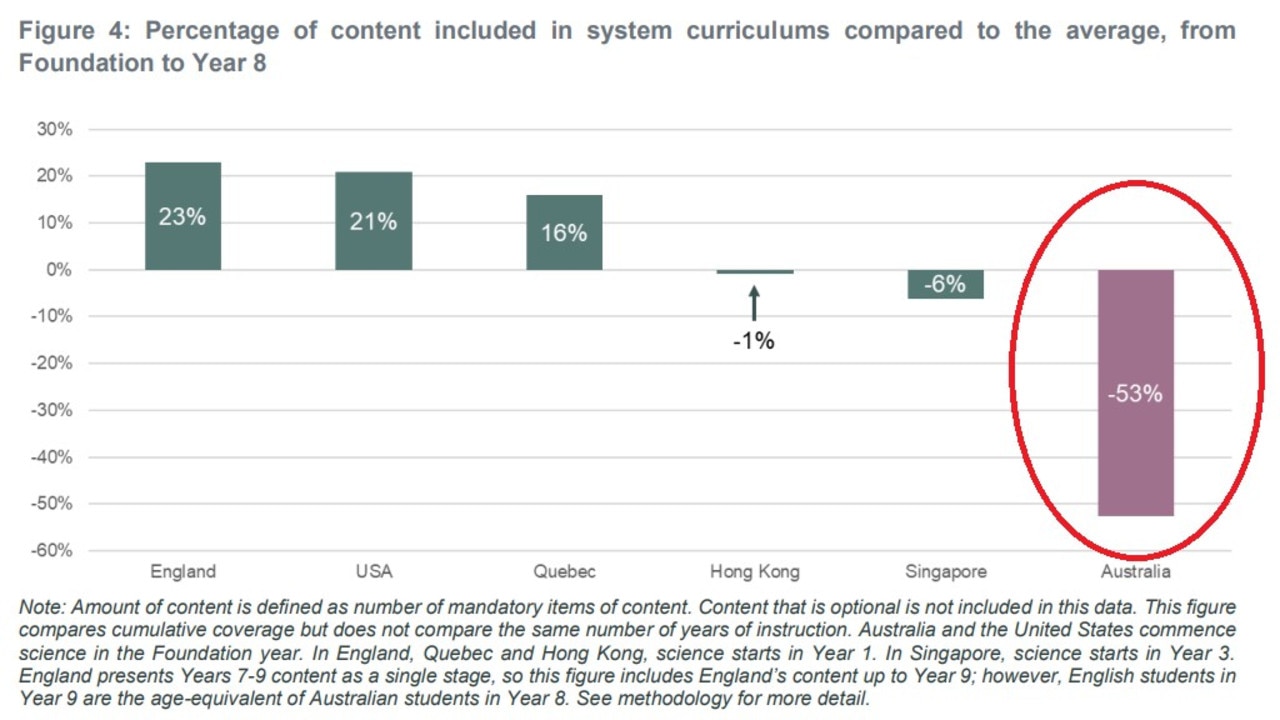

To support their proposal for a new science curriculum, the report formulated key statistics comparing the performance of current students to students before the curriculum change. Learning First also looked at Australia’s performance compared to Canada (Quebec and Alberta), Hong Kong, Japan, Singapore and the United States (USA). In summary it showed a decline in student capabilities and a lack of topic specificity.

On average, Australia’s best performing subject is Chemistry.

From foundation to year 8, a total of five out of 44 subjects are covered in depth. That is approximately 11.4 per cent of the curriculum thoroughly taught.

This is a stark contrast to other schooling curriculums, including that taught to students in the US, where 36.7 per cent of their curriculum is taught in depth.

Dr Jensen advises that the key to keeping the curriculum “world class” is to “research what is and isn’t working” and to look at the “benchmarking and what’s happening in schools”.

To remedy this issue, Learning First proposes a complete re-establishment of the curriculum. They stress that small improvements will prove to be ineffective in increasing student results.

They believe that they need to start at the source and look at what makes it difficult to teach on a classroom level.

From there they recognise the need to produce a comparative analysis of the curriculums considered as world class, and the need for constant research to ensure students are not facing inequity.