Australia is in the grips of a health epidemic we’re ignoring, despite the potentially fatal consequences

Joey Fry was just 23 when he fell victim to an increasingly common health issue that almost killed him and totally altered his life.

While alone in his apartment on Christmas Eve in 2019, a distraught Joey Fry made the decision to end his own life.

The rock-bottom moment came after several difficult months of isolation, following the end of a long-term relationship and the departure of his housemate.

“It had been a long downward spiral,” Mr Fry, now 26, told news.com.au. “I was severely lonely.”

He woke up six days later in intensive care, his mother by his side.

He had survived, but Mr Fry was unconscious for some time before being found, with the full weight of his body on his right leg.

“Mum looked at me and said: ‘Sweetheart, you’ve lost your leg.’ It was the most devastating thing to hear from someone I love so much.”

For the next month, Mr Fry was in what he describes as a “medical haze” that marked the first of several hurdles to overcome.

“It was a tough time after that. It was touch-and-go for a while and I had to be resuscitated a few times.”

Victim of a silent epidemic

After a month in the ICU, battling a mix of emotions from shame and anger to guilt, Mr Fry began to “mourn the person I used to be”.

“Eventually, I could feel all of the good things happening – the love and compassion from my family and friends, support from my nurses and doctors, connection with other patients too,” he said.

“I promised myself that when I got out of hospital, I was going to live my life to the absolute fullest.”

The precarious state he found himself in before that fateful Christmas Eve isn’t uncommon, with health experts describing it as a “loneliness epidemic”.

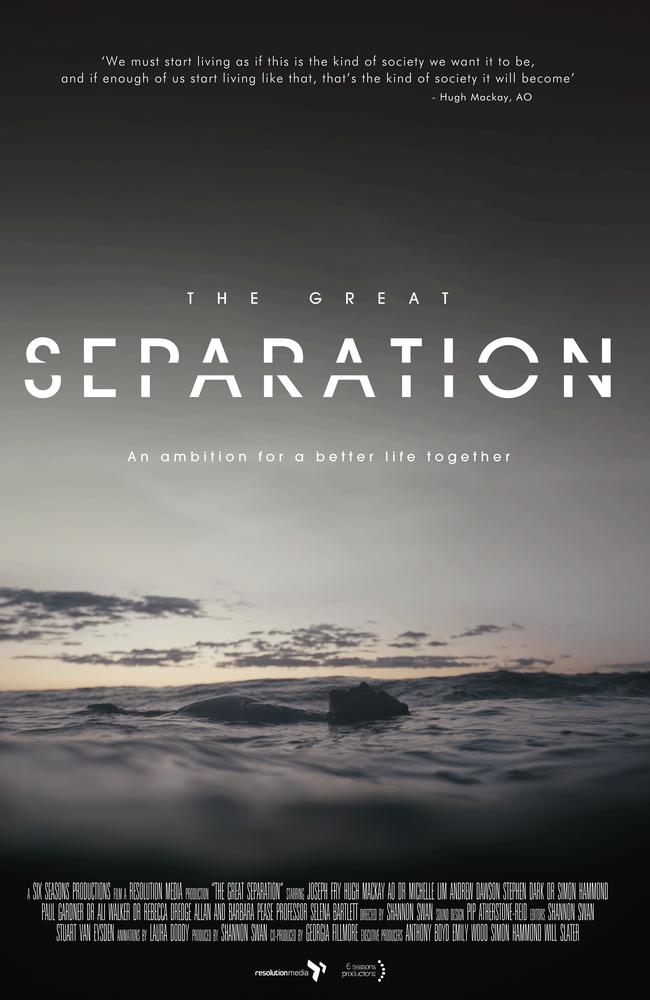

A powerful new documentary called The Great Separation follows Mr Fry as he meets everyday Aussies and experts to uncover the true extent of the crisis.

One of them is clinical psychologist Michelle Lim, who said the health impacts of loneliness are comparable to obesity.

“Science and robust psychiatric literature tells us that when we don’t address loneliness, it increases the likelihood of serious cardiovascular health problems, our immunity, cognitive issues like Parkinson’s or Alzheimer’s, and even early death,” Dr Lim said.

The latest State of the Nation report showed one-in-three Australians feel lonely while one-in-six experience “severe” levels of loneliness.

As well as physical health consequences, they are likely to experience myriad mental health concerns.

And there’s also a significant broader cost to the community, Dr Lim said.

“They’re more likely to use health services, less likely to be productive and engaged at work, so there are economic flow-on effects of an estimated $2.7 billion annually.”

Humans are not designed to be independent, Dr Lim explained.

“We’re interdependent. Humans are innately social to such an extent that loneliness is not that different to feeling hungry or thirsty. That’s how basic a need it is.

“When we don’t eat or drink, there’s a physiological response, and the same can be said for loneliness.”

The changing state of the world means becoming disconnected and experiencing loneliness is becoming more prevalent.

Contrary to some perceptions, it’s not just something older Australians might battle, as the documentary highlights.

“There are so many people going through this,” Mr Fry said. “But it’s really not spoken about. It was comforting in some way to realise that I wasn’t along, but it’s scary too – this is so common.”

Beginning a new life

Award-winning filmmaker Shannon Swan was driving home from work one night, flicking between radio stations, when he settled on Triple J.

“There was this voice I heard of this young kid, which of course was Joey, telling this incredible story,” Mr Swan said.

Mr Fry had phoned in to talk about a track on high rotation at the time, “Slowly Slowly” by the band Blueprint.

“It’s about getting back to basics, enjoying life again, feeling connected to friends and family. I had an inclination to call in and have a conversation about why I loved this song so much, and a little about my story.

“Shannon heard it, tracked me down on social media, flew up to Newcastle to meet me, and the documentary went from there.”

Mr Fry described that call as “life-changing”, aiding his recovery journey and giving him a greater sense of confidence about his future as a person with a disability.

“Putting myself out there so vulnerably, I found it to be quite cathartic,” he said.

“I hadn’t really processed all of my emotions. To do so in front of a camera, I thought it’d be intense but it wasn’t. I’m on the other side and I can now share my story.

“I felt like there was a reason I was still alive. I felt there was something around the corner. Then, this documentary happened.”

Before that Christmas Eve, Mr Fry worked as a plasterer. A chance encounter last winter has thrown him on a dramatically different path.

“Before I lost my leg, I loved snowboarding. Now I ski. It was always a goal to be able to get back to the snow. I’m almost inspired by myself that I can hit the slopes with one leg.

“I was there [in 2022] and someone tapped me on the shoulder and said, ‘You’re ripping. How long have you been skiing?’ and I said, ‘This is my fourth day’.”

More Coverage

He was invited to take part in a snow sports training academy this winter before securing a spot in a similar program in Colorado in the United States.

“The end goal being to make the Paralympics in 2026. I head off in November. I’m giving it everything I’ve got.”

The Great Separation is available to stream for free on SBS On Demand