The vital conversation about mental illness stigma we aren’t having, ignoring 700,000 Aussies

A lot of progress has been made reducing depression and anxiety stigma, but 700,000 Aussies have excluded from the conversation — with deadly consequences.

Such significant progress has been made in breaking down the stigma surrounding depression and anxiety that many people might think the battle has been won.

But some 700,000 Australians living with complex mental illnesses have inadvertently been left out of the conversation.

Away from increased and awareness, on the fringes of the important discussions, are those who battle conditions like psychosis, personality disorder and bipolar.

Anne Deveson Research Centre founding director Michelle Blanchard said a large cohort of people still suffer discrimination — with often deadly consequences.

“People who live with complex mental health conditions are at far greater risk of suicide,” Dr Blanchard said.

“For example, people with borderline personality disorder, which is arguably the most stigmatised mental illness, are 45 times more likely to take their own lives.”

To put that in perspective, Australians with the most severe cases of depression are 20 times more likely to die by suicide than the general population.

“The more complex the illness, the higher the risk of suicide,” she said.

This week, SANE Australia launched the Anne Deveson Research Centre to focus on these complex, little understood and rarely discussed conditions.

The first major project carried out will be a national report card on stigma, looking at the social outcomes of stigma in areas like employment, housing, justice, personal lives and family relationships.

It’s one of the first major investments in efforts to better understand complex conditions.

“Most of the research done around stigma has focused on more prevalent disorders like depression and anxiety so there’s not a lot of data on complex illnesses,” Dr Blanchard said.

An estimated 690,000 people live with complex mental health disorders but they have fallen through the gaps when it comes to understanding and awareness.

“There’s been some fantastic work done over the past 20 years to destigmatise those more common or prevalent mental health conditions,” she said.

“An unintended consequence of that activity is making more complex issues look too tricky or scary. There can be a bit of a sense that we’ve been having this conversation for a long time and surely stigma isn’t there anymore.”

The reality is that there are big parts of the conversation we have missed and Australia has a long way to go, she said.

People with complex mental illness have lower life expectancy rates, high rates of suicide and are less likely to seek help.

“A large number also find it difficult to secure employment and Australia has one of the worst unemployment rates for people with mental illnesses in the world,” Dr Blanchard said.

“On a personal level, stigma can result in people feeling quite lonely and isolated. Focusing on the social outcomes of stigma, alongside the clinical elements of research, is so important and so important.”

Big thanks to everyone who came along today to help us launch @ADRCAustralia. An exciting new chapter for @SANEAustralia. pic.twitter.com/St9xGEKBnp

— Dr Michelle Blanchard (@MischaBee) 22 November 2018

The findings of the report card, which will be based on a national study of people living with complex mental illnesses to begin next year, will be used top direct services to where they can have maximum impact.

“But on a really simple but important level, it will also give voices to people who are often left out of the conversation,” Dr Blanchard said.

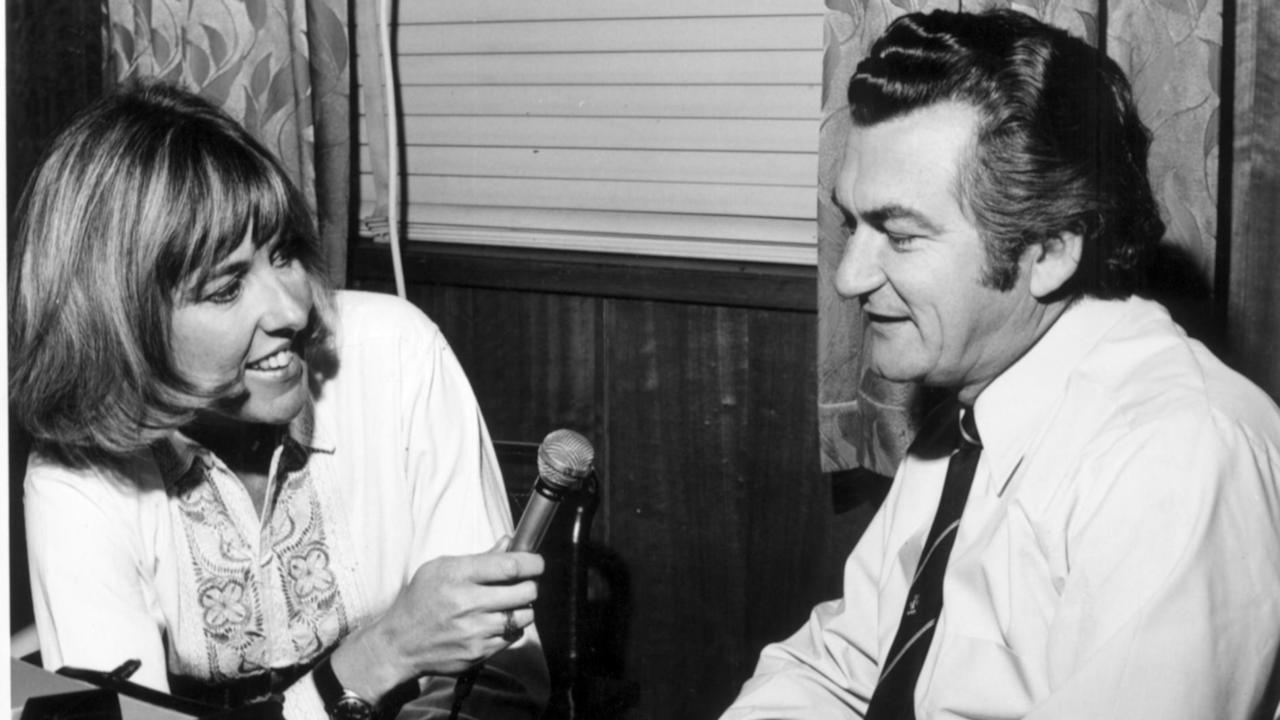

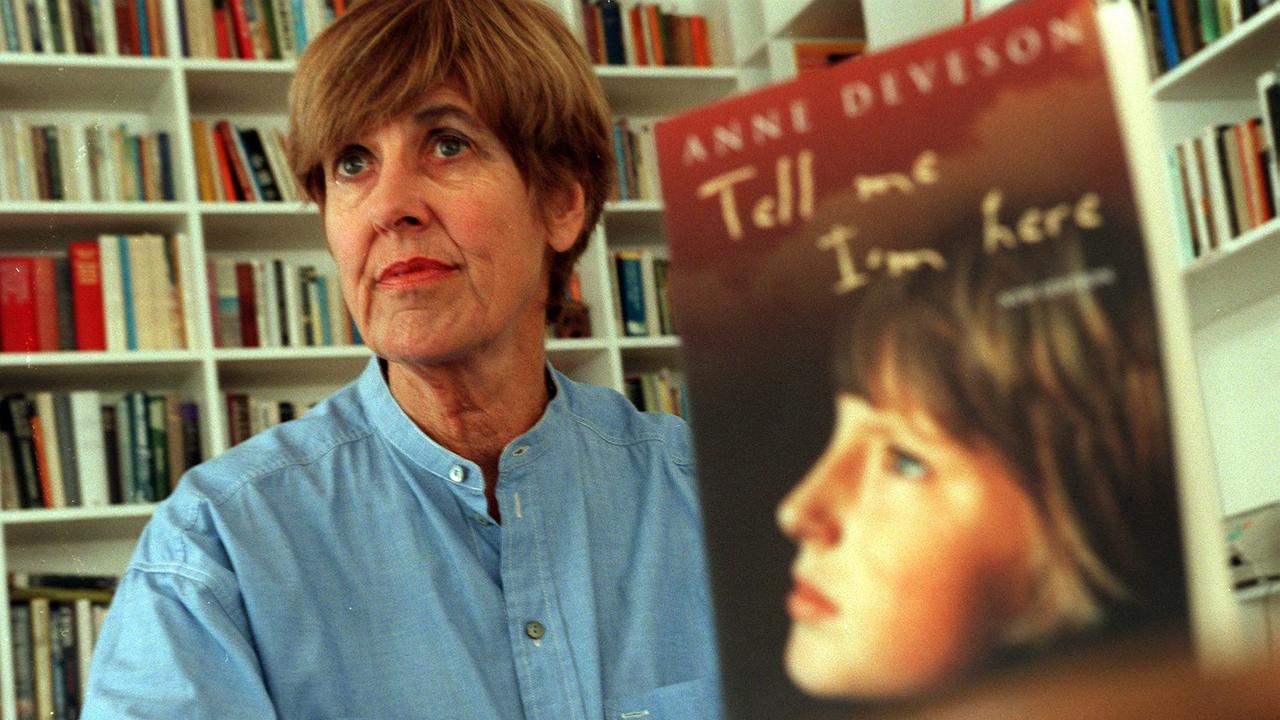

Anne Deveson, who the centre was named in honour of, was a broadcaster, writer and media personality who became a household name in Australia from the 1950s onwards.

Her son Jonathan battled schizophrenia and after his death from a drug overdose in 1985, she became a tireless advocate for the rights of people with mental illness.

Ms Deveson was a co-founder of SANE Australia and became a voice for thousands of Australians, sharing stories about living with mental health conditions.

“She was one of the first high-profile Australians to tell her family’s story,” Dr Blanchard said. “It was incredibly rare for someone like her to be out there telling her story.”

Her book Tell Me I’m Here, about her son’s illness and death, and the ramifications for her family, was a bestseller and won multiple awards.