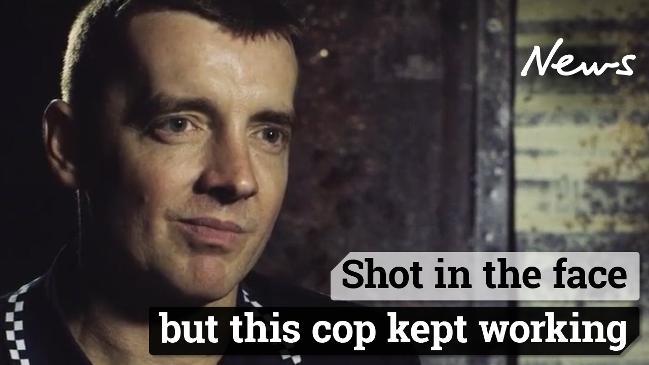

Daryl Elliott Green was shot in the face at close range and again in the arm, leaving him with PTSD

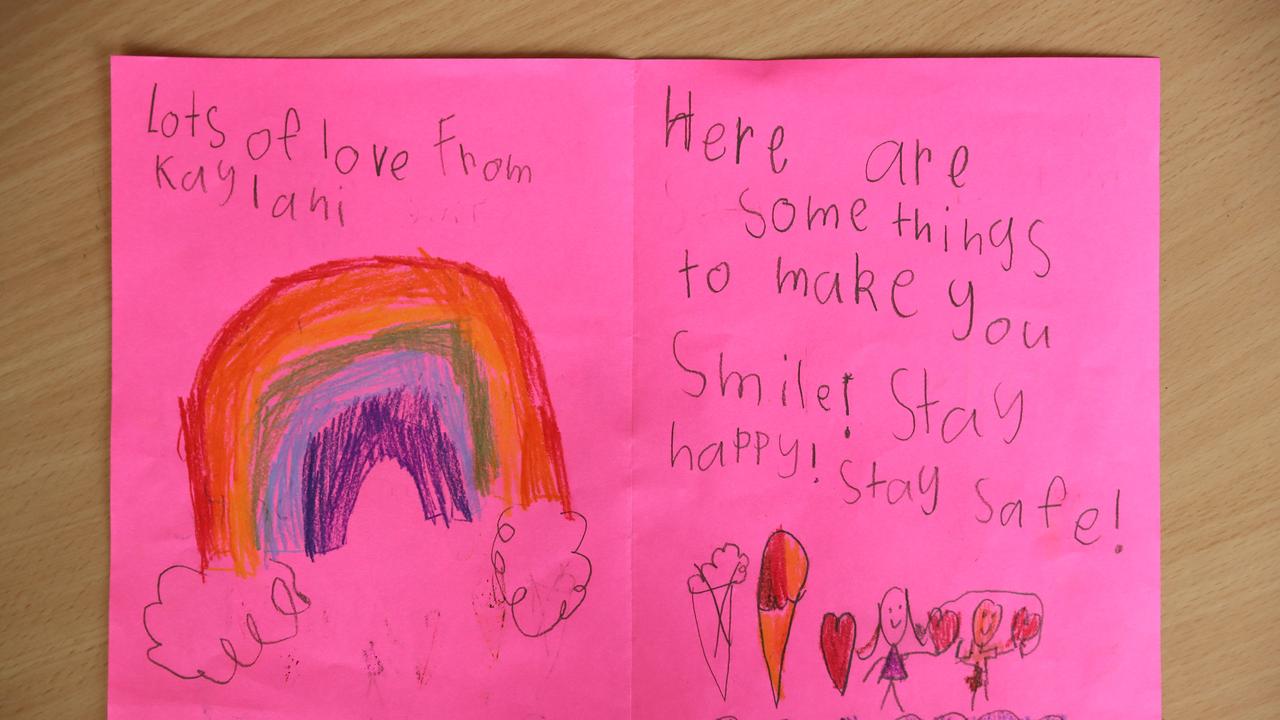

After being shot in the face at close range, three special coffee mugs play an important role in helping Daryl Elliott Green cope with PTSD.

Three seemingly ordinary coffee mugs play a big part in helping Daryl Elliott Green get through difficult days.

He has a cherished ritual of making a cuppa, beginning with carefully grinding his artisan beans and ensuring the water is the perfect temperature, before finally picking the mug that will hold his brew.

Nineteen years on from being shot in the face at close range, and again in the arm, the veteran policeman has found the simple things help with his lingering trauma.

“There’s one I bought when I was on holiday in the Philippines with these palm trees on it,” Daryl explained.

“I love that one. It reminds me of the beautiful tropical islands there, like Boracay. Absolutely gorgeous. If I’ve got a holiday coming up, I might use that mug to remind me that I’ve got something to look forward to.”

RELATED: Meet some of the men who’ll die this week

A second mug he brought in Berlin in 2006 when he was there for the World Cup — taking a break from a series of painful facial reconstruction surgeries — is emblazoned in black, red and yellow.

“A good mate of mine lives in Berlin. I was best man at his wedding. That mug reminds me of the people I love, the importance of relationships in my life. People I’m looking forward to seeing.”

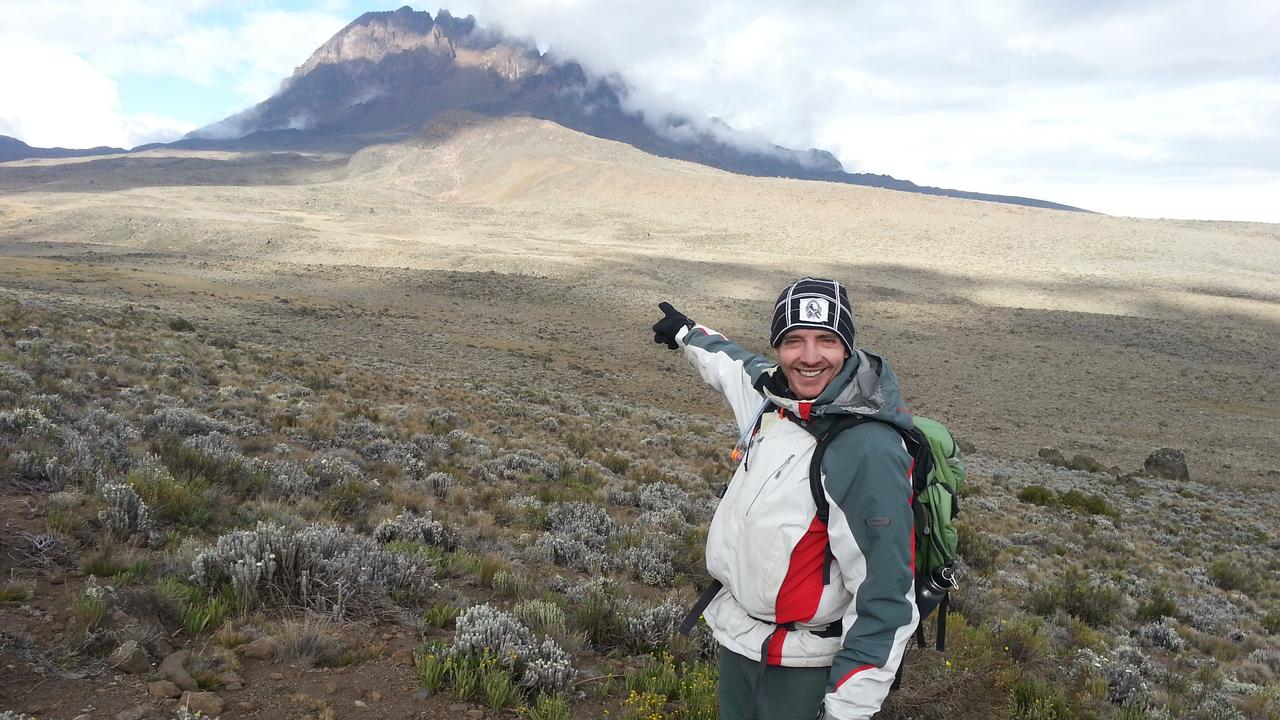

The third is one he bought in 2013 to commemorate climbing Mount Kilimanjaro in Africa — the highest mountain on the continent.

That one reminds him he can get through anything — being ambushed by an armed madman, the painful rehabilitation that followed or a challenging work issue.

“No one knows, but I’m drinking my coffee out of that cup and it tells me that if I can climb that thing under pretty tough circumstances, I can get through that day.”

This week is Men’s Health Week, and news.com.au is running the second instalment of its Let’s Make Some Noise campaign to highlight the serious mental health issues plaguing Aussie blokes.

Emergency services workers and first responders are at considerable risk of mental health battles like post-traumatic stress disorder and anxiety conditions due to the confronting nature of their jobs.

Daryl’s harrowing and miraculous survival after he and two colleagues were ambushed by an armed attacker left him struggling mentally for many years.

It was early in the morning of May 1 in 2000 when Daryl, a Queensland Police constable, and his partner, Sharnelle Cole, were called to a cul-de-sac in the Brisbane suburb of Chermside West.

A man in the street had a falling out with a neighbour, Nigel Parodi, over a $20 football bet.

“There were other things that had gone on, but that was the straw that broke the camel’s back,” Daryl said.

“On the Sunday, Parodi said to a third person who lived opposite him that he was going to go over and kneecap the bloke, put him a wheelchair. They knew he had a firearm so they took it seriously.”

When the man came home from work and learnt about the threat, he called triple-0 and the call came through to Daryl and Sharnelle. They were having a night shift coffee break with their supervisor, Sergeant Chris Mulhall, and so the trio decided to respond together.

“We went around and spoke to Parodi, had a word, and then went back to the patrol car to do some background checks. There was no imminent threat, but we had to do some checks and decide whether to execute an (emergency) search or go to a (judge) to get one.

“Chris was in his car making a call on his mobile phone, and Sharnelle got in the front passenger seat, with me in the back listening in.

“I left the door open because we were only going to be a few moments. I was sitting there listening when all of a sudden I heard this tap, tap, tap.

“It was 3.50am in a quiet cul-de-sac. It was a good neighbourhood. We’d never been called to this neighbourhood for anything serious. I wasn’t overly concerned.”

As he turned to his left, Daryl was shot in the face at close range with a .22 rifle, fitted with a homemade silencer.

The force threw his body across the car. He was shot a second time in the arm.

RELATED: In a year PTSD has killed more soldiers than the whole Afghan conflict

“Chris heard me screaming, looked over and saw me and thought I was dead. He then got shot once in the arm and again while he was later giving chase.

“He dropped his phone and it landed on the road so the entire thing was recorded. Then Parodi moved up and shot Sharnelle in her left-hand side.”

The several-minute audio of the confusion make for harrowing listening. Daryl can be heard screaming after the offender, calling out his boss and pleading with his partner to hold on.

She can be heard quietly groaning in the front seat, while Daryl ran off to search for the man who had attacked them.

“I got up and drew my firearm … I got into fight mode and got angry. I was screaming out. I couldn’t find Chris, I was worried he was lying in the street. I couldn’t find the offender, so I moved to the car,” Daryl said.

“There were two people standing around, a lady who said ‘don’t shoot!’ so I screamed for them to get back into the house. I saw another figure and thought it was the offender, but it was the lady’s husband.

“I ran back to the car to stand guard over Sharnelle. The adrenaline was starting to wear off, so I was feeling everything by this point. I rested on the front of the patrol car with my firearm in my right hand, holding my mouth with my left hand.”

The three wounded officers were rushed to hospital, where Daryl was first into surgery. He had lost a significant amount of blood, and his condition was critical.

It took three hours to extract the bullet from his head, after it shattered his jaw and teeth, went through his tongue and became lodged in the back of his throat.

For several years, Daryl went through a series of surgeries, reconstructions and rehabilitation, but the mental challenges proved to be some of the most daunting.

“Until about a month in, I was pretty numb. I’d been shot in the head from a metre away, and I was still alive, and so I couldn’t believe it — it was like I was living in a haze.

“About seven weeks after we were shot, Senior Constable Norm Watt from the Rockhampton dog squad went to a domestic violence incident and was shot once in the leg, severed an artery and died.

“I went into a downward spiral after that. I slumped into a deep depression. I was having awful dreams. I thought I was going crazy. I knew things weren’t right.”

A fellow officer who had been involved in a shooting noticed the symptoms — anger, upset, confusion — and gave Daryl the name of a psychiatrist.

He began treatment for depression, anxiety and panic attacks, as well as suicidal thoughts, before focusing on the post-traumatic stress disorder that had set in.

“A door would slam shut, and I would jump out of my skin. I was hyper aroused about everything. That sort of stuff made me really angry.

“One of the key people to counsel me was a Vietnam veteran. I was talking to someone who’d walked the walk. He put me through exposure therapy, which was a great help.”

A big part of the mental healing process were the physical milestones, including getting back his teeth.

“I wanted my mouth back — that was my aim,” Daryl said.

He also wanted “the old Daryl” back. It took him almost a decade to realise he wasn’t going to return and to accept it wasn’t a bad thing.

“It took me many, many years to realise that we’re all made up of our experiences, so you’re not going to be the person you were at 20 when you’re 30, 40 or 50, regardless of what happens,” he said.

He returned to work as a firearms and combat instructor. In 2006, he was asked to speak to a group of recruits about what he’d experienced.

“I didn’t want it to be a war story. I played the audio of the shooting, drew a diagram on the board and spoke for about an hour. It was practical training.”

His boss sat in and was impressed, which led to Daryl speaking to more recruits before addressing larger groups of more senior officers.

A cop’s wife approached him to talk at a corporate team-building day, which sparked a new endeavour — Daryl now travels the country to share his story of resilience in the midst of unimaginable trauma.

“Oh yeah, I still struggle sometimes, definitely,” he said.

“It’s amazing what triggers it. A mass shooting in America, a terrorist attack, a police officer being injured in the line of duty,” Daryl said.

“There’s a person, just like me, out of the blue they’ve been injured and have a long road ahead of them, physically and mentally. I know what that’s like.

“I’ve got a lot of coping strategies. I focus on the healthy things. I prioritise sleep, I plan things to look forward to.

“And I love my coffee in the morning — I make a big effort to grind my own beans and really enjoy it. I like full-cream milk, only a small amount because I like it strong. No sugar.

“I went to the Commonwealth Games and took my own grinder and machine. I like it. It’s a good little ritual and a great way to start the day. It’s something to look forward to.

“And of course, I’ve got my three mugs.”

Daryl has received a number of commendations, including the distinguished Queensland Police Service Valour Award, and is now a senior sergeant.

He is a speaker, mental health and suicide awareness campaigner and Lifeline ambassador.

Parodi’s body was found in bushland three weeks after he attacked Daryl, Sharnelle and Chris.

• If you or someone you know needs help, contact Lifeline on 13 11 14 or visit lifeline.org.au

In an emergency, call triple-0