How ‘clean eating’ led to years of pain for two young women

Queries regarding orthorexia nervosa – sparked by a desire to be “healthy” – has increased to The Butterfly Foundation’s helpline.

For thousands of high school students around Australia, getting their height and weight measured in front of their classmates is part of the curriculum.

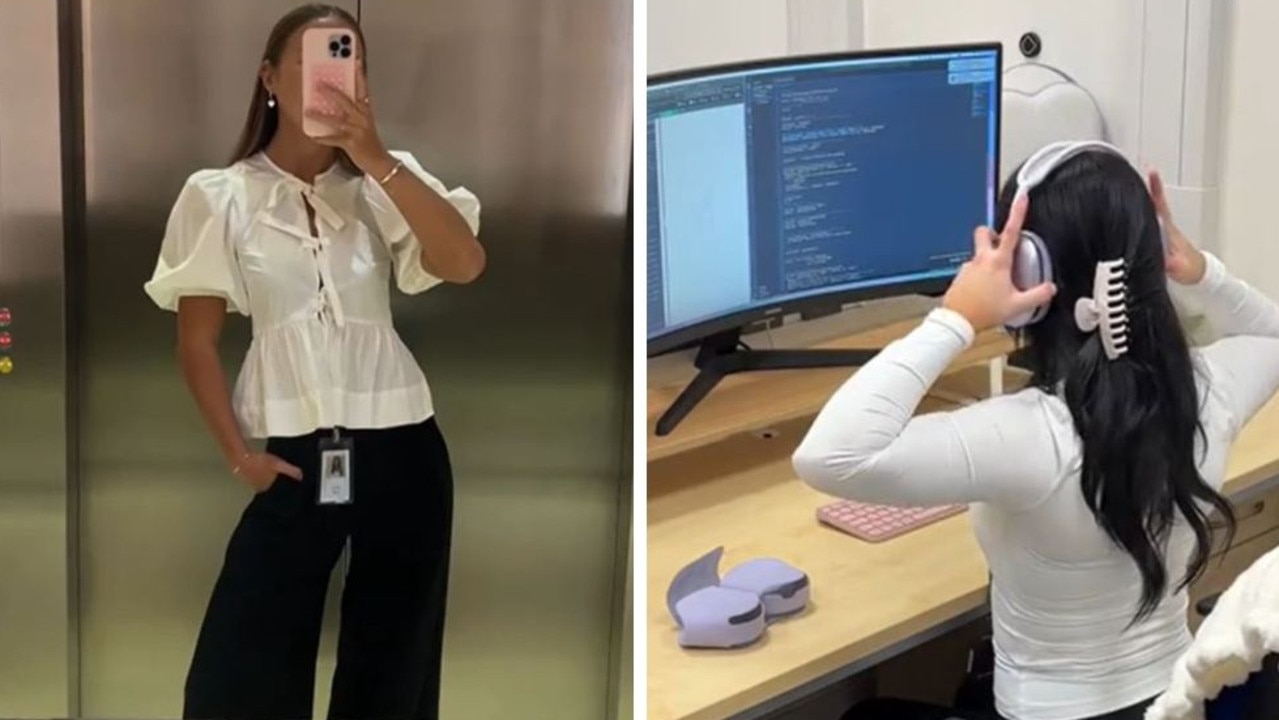

But for one woman, Sophie Smith, now 23, the act sent her down a dark, constant path of “eating clean”, exercising and weighing herself.

The examination, when she was just 15, indicated that the Perth local’s BMI was growing – something she now dismisses as inaccurate – as she got older and put on weight, but her height hadn't changed since she was 13.

“I basically just got like really worried that I was going to be ‘overweight’ and be unhealthy,” Sophie told news.com.au.

“Health is a prioritised thing in our culture, it’s obviously seen as bad if you’re unhealthy so I basically started trying to lose weight to not tip over into being classified as overweight.”

The label of being “overweight” distressed her and, despite taking dance classes, she performed additional workouts at home and started dictating items such as brown rice only at meal times.

Stream the news you want, when you want with Flash. 25+ news channels in 1 place. New to Flash? Try 1 month free. Offer available for a limited time only >

Soon, it became an obsession that grew out of control and eventually, Sophie was diagnosed with orthorexia nervosa.

There is debate whether orthorexia is a subset of anorexia or if it is an entirely different mental health issue in it’s own right.

At it’s core it’s about how “healthy” eating and exercise routines become restrictive, obsessive and impact every detail of one’s life.

Dr Tania Nichols, a psychologist who works with The Butterfly Foundation, said: “It shares many characteristics that would be really, really similar to anorexia nervosa, but I guess it can be separated by the underlying primary goal.

“So if we think about anorexia nervosa, the underlying goal there is weight loss. But [with] orthorexia nervosa, there may be weight loss as a result, but the underlying goal is obsessive focus on healthy eating.”

She said there has been an increase in queries regarding these eating behaviours masquerading as clean eating to the Butterfly helpline, adding the disorder doesn’t discriminate based on gender, cultural background or socio-economic status.

Dr Nichols said that already restricting your diet for health reasons – such as having coeliac disease or irritable bowel syndrome – can have a knock-on effect as the illnesses can create anxiety about becoming sick.

For Sophie, the signs built up over time. She didn’t see her lifestyle as an issue.

It wasn’t about losing weight or being a certain size, but about her health – stopping her from eating things like chocolate. Eventually she became a vegetarian, over fears of claims about processed meat, matched with a family history of bowel cancer.

Her own eating disorder created a ripple effect that impacted her mental health and her relationships with others, because her mood became influenced by what she’d seen on the scale.

“If other people were getting in the way of my eating disorder plans – for instance if we went out for dinner to a place I didn’t approve of – I’d get angry with my family for choosing it,” she said.

“I damaged some of my relationships, especially with my mum and my twin sister Eloise. We have a great relationship now, but at the time I had a twin without an eating disorder and I definitely became jealous of the fact she was just able to eat freely and have all this food I wasn’t allowing myself to have.

“I would think things such as: ‘How come she’s not feeling guilt ridden after eating cake?’”

Sophie fought for her obsession to go undetected, ensuring never to appear underweight. Looking back, she suspects her family suspected something was wrong.

It wasn’t until Sophie was sitting next to Eloise on a flight back to Perth after a family holiday plane that she realised something had to change.

“That’s when the kind of light bulb moment happened. And I realised, ‘Maybe this is not sustainable, maybe there’s something going on here’,” she said.

“It was because of my sister that I really was able to start the process of recovery because she was studying a general education course on nutrition.

“The lecturer was a woman who had lived experience herself with bulimia, who had recovered and specialised in eating disorders and knew a lot about it.

“My sister suggested that I go talk to her about it. And so that really was my introduction to recovery and to the idea of maybe that could be an eating disorder.“

Sydney-based Alicia Michelle Glen has her own story of orthorexia after a breakdown in her relationship promoted her to seek out control to fill the void that had formed.

The competitive gymnast said she woke up one morning and began to criticise everything about her appearance.

“I took action immediately, because I didn’t see myself as ‘small’ anymore,” she said.

“Yet at this stage I was in a good weight range, was 20 years of age, exercising regularly and eating in a fairly balanced way – so I was already ‘healthy’.”

But Alicia’s history of competitive gymnastics meant she was taught that winning and achievement was everything.

“These things essentially would only be possible if we kept striving towards an unrealistic ideal of ‘perfectionism’,” she said.

“We were conditioned to be strong, in control and resilient; which was a blessing and also a curse as I was to later find out in late 2015 when I innocently wanted to ‘lean out’.”

She fell into a habit where all she could think about was what she was eating for her next meal, how many calories she was consuming and how she could burn them.

“I also thought a lot about Sundays where I would allow myself to have an ‘unhealthy’ dinner and dessert – of which I would go overboard and essentially binge,” she said.

“Then I would start all over again on Monday. I was always thinking of ways I could cut calories out of my diet which was incredibly unhealthy because it affected my social life for sure as I never went out to enjoy food.”

The illness gripped her for three years. Like Sophie, it seeped into the 27-year-old’s relationships with those around her.

Alicia’s relationship broke down, her family became worried as her weight dropped to dangerous levels, and she refused to go out because she wanted to control what she ate.

Eventually she knew things needed to change and she sought help with how to tackle the illness.

Both young women went down different avenues in order to address the issue.

Sophie went the traditional route – seeing a psychologist and dietitian fortnightly – before it was pushed out to monthly as she addressed her core belief of what being healthy meant. It’s now been three years since she fully recovered.

While Alicia initially saw a psychologist, they were only able to help her through some aspects of the illness.

“I was still trying my hardest ‘not to put on weight’ … I was still in denial while I was initially seeking treatment,” she said.

“I was ‘pretending’ that I was healing to make those around me happy … it was a very difficult period. Counting calories actually made things worse and heightened my obsessive/controlling tendencies – I even weighed lettuce!

“It turns out, the treatment I was receiving only focused on healing the ‘symptoms’ not the ‘root cause’ of things.”

After starting her first business in 2018, she was invited to a spiritual healing event that opened her eyes to alternative methods.

“It was only a few months into that coaching/healing program where I stopped ‘identifying’ with my ED and began seeing myself as a spirit in a human body having a very interesting experience; recognising the impermanence of all there is … I felt whole once again.”

Sophie said there are so many misconceptions about orthorexia, calling it a “socially acceptable eating disorder”.

“No one ever sees a problem with you just having a lot of willpower to do exercise and eat healthy,” she said.

“They can’t see the stress and what happens when you don’t do those things – how bad you feel and how obsessive and rule driven it.”

She shares her story so others know there is no “face” of eating disorders and, just because someone doesn’t look a certain way doesn’t mean their mind isn’t completely gripped by one.

“I thought it had to be like this thing where you’re knocking on death’s door. That really wasn’t the case for me. But, as it turned out, that’s just a real big misconception about eating disorders,” she said.

Sophie added that she didn’t even know about the concept of having a relationship with food when she was younger, and thinks, at the end of the day, having a healthy relationship with food and your body is the goal.

She said organisations like The Butterfly Foundation are instrumental for people who need support or information when it comes to eating disorders or disordered eating, with experts to help guide people through the next stage of treatment.

But, despite research about how content about diet and exercise can impact mental health, and an increase in questions to the foundation, orthorexia isn’t formally recognised in the The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders with the fifth edition, published in 2022, not including it.

”It wasn’t included because there was insufficient research into it. And certainly, any of the literature that I’m looking at now, there’s still needs to be further examination around the development of adequate sensitive tools to differentiate or potentially differentiate orthorexia from other disorders,” Dr Nichols said.

“Because in order for it to be a separate distinct disorder, we have to sort of be able to say that a person’s level of distress and well being is affected by the concern around healthy eating.”