Devastating story behind photo of Bachelor Matt Agnew

At first glance, Matt Agnew would seem like he had it all. But there was a sad reality that Australia never knew.

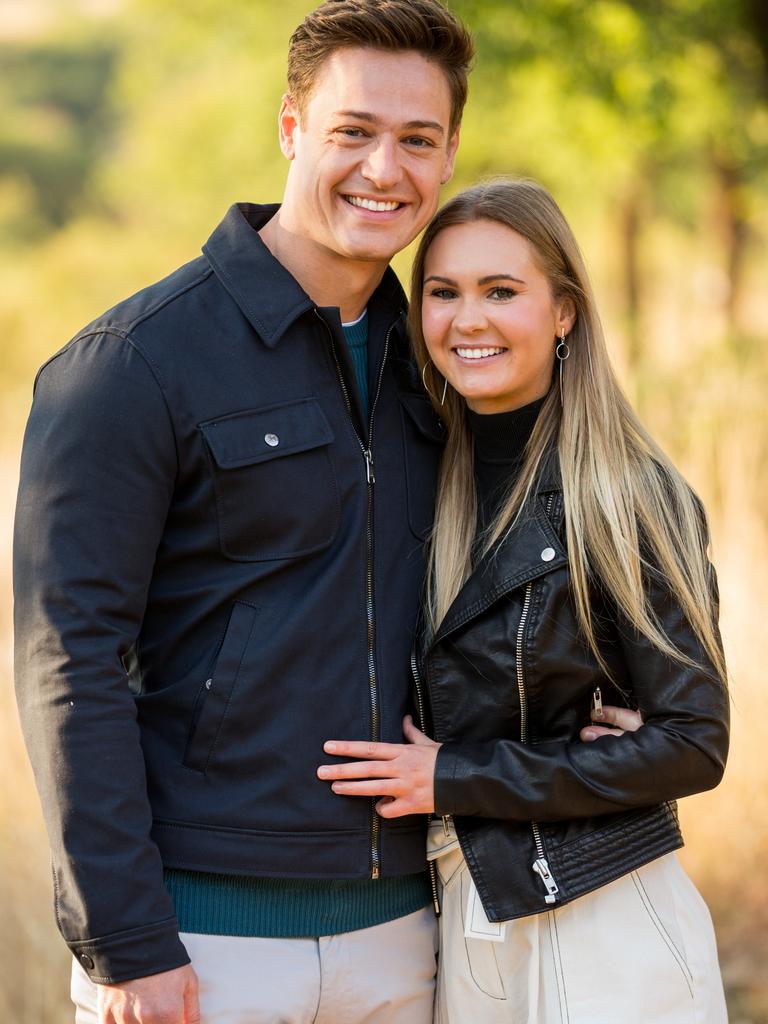

When Australia was introduced to Dr Matt Agnew as Network 10’s 2019 Bachelor, the country collectively fell in love with his charm, striking good looks and love of all things science.

That glossy image, however, soon revealed itself as a curse, and in combination with the fallout of the reality show, was a beast that has continued to haunt the now 36-year-old.

Agnew, an astrophysicist, revealed that while he had experienced a “salad of mental issues” since his early 20s, they came to a head in the months and years following the program.

Upholding the impossible task of what he felt was an expectation to present his life “perfectly”, had a negative impact on his mental health and body image.

The public’s response to his short-lived post-Bachelor relationship with chemical engineer Chelsie McLeod also had a massive impact on Agnew who said he “did not cope” with the fallout.

“I struggled. I did not cope. I hit some pretty dark times after that and I’m glad I got through,” the robotronic enthusiast told news.com.au.

The severity of his mental difficulties were stark but, as a direct outcome of his courage to speak openly about them, have since shaped important conversations in rooms across the country.

He joined Beyond Blue as an ambassador and has most recently been advocating for the organisation’s Big Blue Table initiative, which encourages Aussies to host casual meals in the spirit of connection and raising money to continue funding the crucial 24/7 support service.

Agnew expressed the importance of crisis resources, particularly given time and financial constraints of traditional psychiatric treatment, which was not always accessible to everyday Australians.

“The really challenging thing with this is that I was in such a privileged position to be able to afford all of these resources that not everyone has access to,” he said.

“It [mental illness] is really hard to get through, I got through because I had this quite comparatively luxurious position.”

At his worst, he said his symptoms felt insurmountable.

“I don’t know how one can really battle their way through without access to all those resources,” he said.

“I’m really grateful I had access, but it really highlighted for me this massive chasm that has to be crossed by someone going through the kinds of things I did, and often worse, without having the same resources I had.”

While Agnew has for the past decade been navigating life with anxiety and depression, he was more recently re-diagnosed with bipolar 2, which he was told often manifested in a similar way to his former diagnoses.

“I’ve had some really dark times. I’ve spoken candidly about some of these things, and they’re still hard for me to talk about,” he explained.

His darkest point was in 2021, when his mental illness led him to begin “putting things in place” to end his life.

“That’s probably the lowest I’ve ever been,” he said. “I did fortunately make it out, which unfortunately is not the case for many Australians.”

He credited his survival to leaning on friends and loved ones, the right combination of medication, psychologist and psychiatric support, and an understanding of how his mind worked.

Agnew said he now acknowledged the unique and inevitable chaos of being part of a reality dating program was not well suited to him and, while support was made available, it was unlikely to be enough to cover off every participant’s broad scope of mental needs.

Suicide of reality TV contestants has long cast a dark cloud over the hype, particularly in the UK where multiple stars have taken their lives after re-entering normality.

One way to “get the upper hand”, Agnew said, was by maintaining relationships and having discussions around mental health with loved ones.

“Get involved with something like the Big Blue Table initiative, and the funds raised helped no call go unanswered. Plus it’s easy to do, you just have a meal with your friends,” he said.

“It could be a picnic in a park or catching up for a barbecue. Something really simple.

It’s about creating that safe space with your nearest and dearest, having vulnerable conversations and trying to normalise these things. Mental illness thrives in isolation.”

brooke.rolfe@news.com.au