Cognitively impaired woman isolated for 23 hours a day, inquiry told

A vulnerable woman was subjected to ‘filthy’ and ‘inhumane’ incarceration, including seclusion for 23 hours a day, an inquiry has heard.

A cognitively impaired woman was confined to “filthy and degrading” secluded detention for 23 hours a day over several years, the disability royal commission has been told.

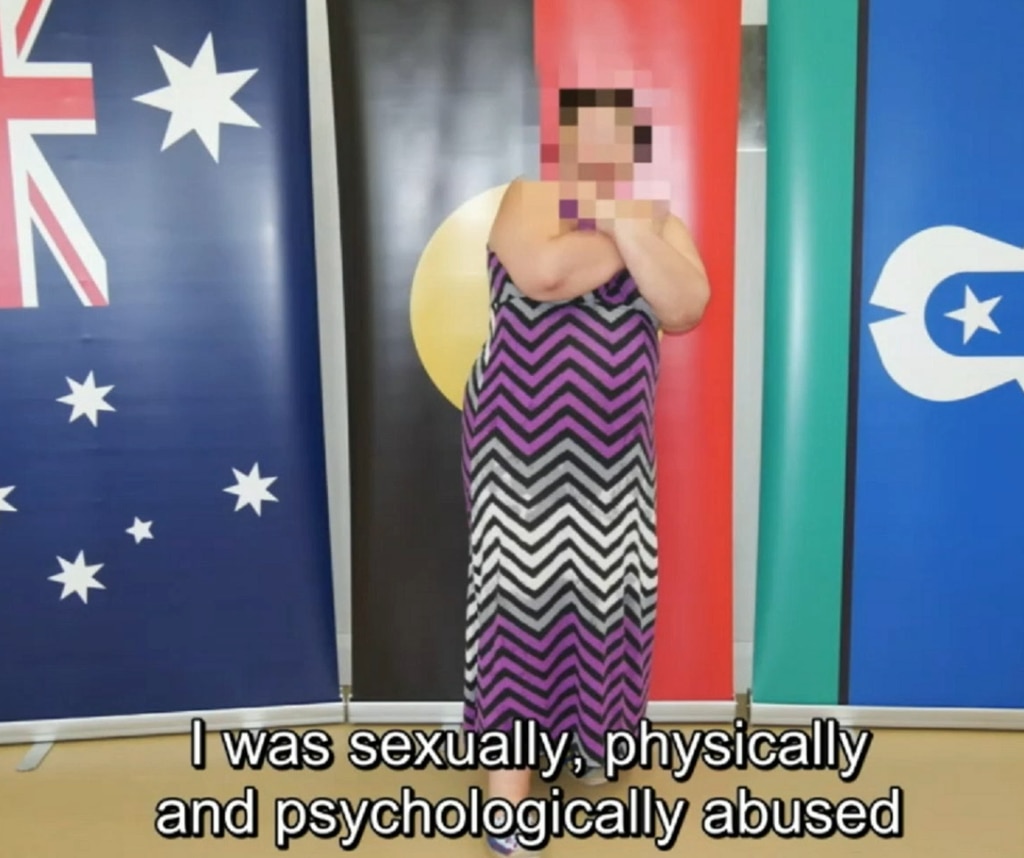

The inquiry heard from Melanie – not her real name – an autistic Indigenous woman who suffered an “extraordinarily troubling” childhood, including sexual, physical, and psychological abuse.

In an audio recording, the 38-year old told the inquiry she had been “in an out” of juvenile incarceration throughout her adolescence.

Melanie has been diagnosed with various diagnoses, including intellectual disability, borderline personality disorder, and extreme self harm behaviours prompted by “severe and prolonged” abuse.

She said was in a “dark horrible, horrible place” while incarcerated at age 16 and resorted to “severe” self harm.

The inquiry heard she subsequently engaged in two acts of “serious violence”, including an incident that left a juvenile detention staff worker dead and Melanie charged with manslaughter.

After being transferred to adult prison, Melanie was deemed incapable of pleading over the incident due to mental impairment.

She left prison in 2011 and became an involuntary civil patient the following year.

But she was confined to effective isolation between 2014 and late 2020, including seclusion for 23 hours per day, after her mental state deteriorated, the inquiry heard.

“I was down and depressed. I was lonely, I had no one to talk to. I was miserable. I needed human contact,” she said.

“It was inhumane to keep someone locked up for that long in a secluded area.”

Melanie had been detained in various locations for over two decades, the inquiry heard.

Counsel assisting Janice Crawford said Melanie’s conditions were described as “Dickensian” by a forensic psychiatrist.

Ms Crawford said a mental health review tribunal found Melanie’s rooms were “filthy and degrading … and clearly not conducive to any form of recovery”.

“It is troubling indeed that a woman is held in such an environment in Australia in 2020, with little apparent hope of improvement and release,” she said.

“It is more concerning that these conditions have been at times presented and promoted as being therapeutic.”

NSW Public Guardian Megan Osborne visited the space where Melanie was confined early last year.

She said the visit, which lasted only 15 minutes, left her “anxious and overwhelmed”.

“The feeling that I had visiting those seclusion rooms was one that I will never forget and will never leave me,” she told the inquiry.

“(I) knew that I wouldn’t do very well if I had to spend any period of time in those rooms.”

Since November 2020, Melanie was lived in a bedroom within a subacute ward where she was no longer subjected to extended seclusion.

Ms Osborne said a broken foot Melanie suffered expedited the move, saying it would be too difficult to treat the injury and care for her in seclusion.

Tuesday was the first of an eight-day hearing of the Royal Commission into Violence, Abuse, Neglect and Exploitation of People with Disability.

Chair Ronald Sackville said the inquiry would explore ways for the criminal justice system to better engage with people with cognitive impairment.

“Of course there are some hardened criminals in prison. But a very large proportion of people are in prison — or they are primarily and sometimes entirely — because of their cognitive disability,” he warned.

Mr Sackville warned Indigenous people with cognitive disability suffered “appallingly high” rates of incarceration, and experienced multilayered forms of discrimination.

Indigenous people accounted for 29 per cent of Australia’s adult prisoners, despite making up just 2.5 per cent of the population, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics.

“It is hard to describe this phenomenon in any way other than a revolving door of First Nations people into and out of incarceration,” Mr Sackville said.

He warned the criminal justice system had become a “lightning rod for simple answers to complex problems”.

That included an erroneous public perception that crime was on the rise across Australia and that adopting punitive measures would curb the development, he said.

The commission was established in April 2019 in response to community outcry over the abuse of people with disability.