‘Broken’: Hidden side effect of Covid-19

An Australian healthcare worker says the Covid pandemic had an unrecognised toll on many, and shares the moment she realised it “broke” her.

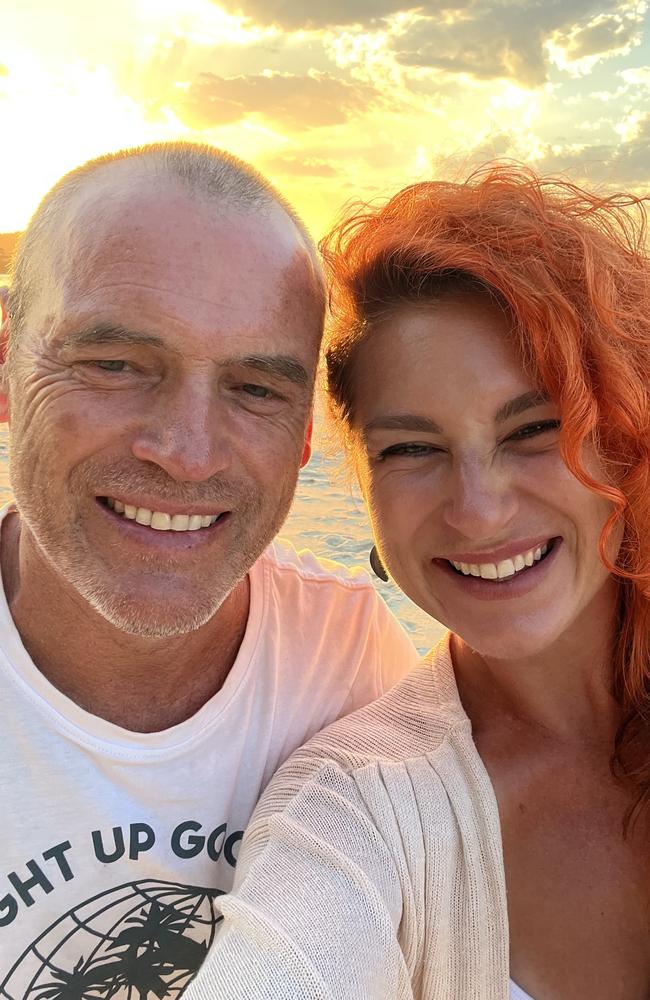

“It took my husband stepping in to help me realise I was at breaking point,” says Adelaide woman Sophie Bretag recalling her darkest moment just a few years ago.

“I was struggling to get out of bed. I was feeling overwhelmed and teary all the time. And then one day he just said ‘you can’t go back in there, because this is breaking you’.”

Having been classed as an essential worker due to her role in HR at an aged care facility, Sophie had been working non-stop throughout the pandemic, in the midst of a workforce deeply traumatised by what it was dealing with.

“It was a really tough time,” Ms Bretag says.

“I love being with the elderly. I was driven by a deep purpose to actually take care of the people who were taking care of the vulnerable people as well. And so when you’re doing that and you’re giving so much the whole time, you’re not going to say, ‘I haven’t got capacity to sit and listen to you’. You’re looking at people touching the glass between them and their loved one to say goodbye. It was a lot. We really struggled, if I’m honest.

“People broke for all kinds of reasons. It broke a lot of people. A lot of people are still broken.”

Australia is in the grips of a mental health crisis, and people are struggling to know who to turn to, especially our younger generations. Can We Talk? is a News Corp awareness campaign, in partnership with Medibank, equipping Aussies with the skills needed to have the most important conversation of their life.

There was a time, at the peak of the pandemic, where to be a frontline worker was the social equivalent of being a war hero.

People clapped on their front doorsteps in the UK to thank the healthcare workers for their sacrifice.

Here in Australia, to hear that someone worked in health or aged care was to immediately acknowledge the outsized burden that person was carrying for the rest of us.

But in the wake of Covid, the mental health impact on these people in particular is another silently unfolding epidemic.

In 2021, more than half of all Australian GPs reported that managing fatigue and burnout was one of their top challenges.

An NIH study measuring the mental health impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic on health and aged care workers found disturbingly high levels of mental health challenges.

More than half of them (59.8 per cent) reported experiencing mild to severe anxiety, 70.9 per cent reported moderate to severe burnout and 53.7 per cent reported mild to severe depression.

Even outside of the health system, Australians are now coming to realise the profound effect the pandemic had on societal mental wellbeing.

New research by News Corp’s Growth Distillery with Medibank shows 72 per cent of Australins recognise the lingering negative impact on mental health. Victorians - the state with the most severe lockdowns - were most likely to be feeling the pandemic’s lingering negative effects.

For Sophie, the warning signs were there for a few years prior to reaching crisis point, though it’s only in hindsight that she could recognise what was happening.

“It was just not being able to stop, not being able to take a break, not being able to pause, and not really realising that I was actually pushing through some symptoms that I probably should have been listening to,” she says.

“I was getting snappier and my empathy for other people lessened,” Sophie continues.

“That started mainly at home with my family, so unfortunately, they bore the brunt of it more than anyone. There was no capacity or availability to be able to let any of that out at work, so it was about holding it all together when I was at work, supporting people, supporting our residents, supporting our families and managing so many different competing pressures at work that there was just no space or support available to actually let it out there.”

“I think it was really hard for my family, because I’m genuinely quite a chatty, positive, upbeat person, and I started not wanting to talk to people, not wanting to communicate, wanting to spend more time on my own and just generally shutting myself off.”

By the time Sophie was in peak burnout, she was feeling intensely overstimulated by ordinary daily encounters (such as her children arguing or people talking over one another to get her attention) and struggling to even get out of bed in the morning, her husband stepped in.

“Having someone I loved give me the permission to drop the load, was exactly what I needed,” Sophie says.

“I didn’t go back in, and I ended up taking six months off to recuperate and heal myself from burnout.”

Seeking help from a psychologist and reintegrating activities that helped her heal her fried nervous system were crucial to Sophie’s recovery, though it was something she describes as a lengthy, challenging process.

“You don’t get better from burnout overnight, it takes sustained effort and a real commitment to changing things,” she explains.

“For me, a big part of it has been getting back into nature. Nature is something that soothes my nervous system, so it’s been a combination of traditional therapy and natural therapy to get me back on track.”

And while the process might have been slow, there were glimmers along the way to let Sophie know things were on the up and up.

“For me, it was when I realised I was enjoying spending time with my kids again,” she recalls, “That was a big thing for me. So instead of being so tightly wound and in my head, I was able to start to be more mindful with my kids and really start to enjoy them again. I knew I was getting better. It’s being able to think more clearly, and be more present in my body.

“I know what it feels like now to get better, so I know what to work towards, but I also know when I’m beginning to slip back into burnout. Because once your body has done it once, it can easily happen again.”

More Coverage

Sophie ended up leaving the aged care industry altogether to work as an HR Consultant and create her wellbeing consultancy Metta Leaders, helping other companies and employees avoid burnout themselves. She trained as a meditation teacher and now uses mindfulness techniques to help other people with what she has learned.

“I think it’s about taking those steps every day to just make sure you’re taking care of you. So that you don’t get so far along that you are broken.”

Bek Day is a freelance writer