Weight-loss drugs are everywhere, but how many Aussies are actually taking them?

Off-label use of diabetic drugs for weight loss has skyrocketed, leading to global shortages in Ozempic, but how many Aussies are actually using these drugs?

A new class of weight-loss drugs touted as a revolutionary breakthrough in obesity management have received global attention, but how many Aussies are actually using them?

Traditionally confined to celebrity and influencer circles, drugs such Ozempic have become widely available to anyone looking to shed a few kilos.

Ozempic has been included in the Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods (ARTG) for the management of blood sugar levels in type-2 diabetes patients after it was evaluated by the Therapeutic Goods Adminstration for its safety, quality and efficacy for that indication only.

The use of the drug for anything other than type-2 diabetes – such as weight loss – has not been approved by the ARTG, and is known as “off-label” use.

Australia, along with most of its Western peers, have experienced a proliferation of off-label prescriptions for this new class of drugs known as GLP-1s.

They have been shown to act as appetite suppressants, by producing a naturally occurring hormone, glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1). The hormone acts to simulate satiety and ultimately, reduce food intake and body weight.

Almost 100 per cent of the market is shared by two pharmaceutical giants. Novo Nordisk, who produce Ozempic and Wegovy (semaglutide) and Eli Lilly, who have recently released their own injectable, Mounjaro (tirazapeptide).

So how many Aussies are actually taking weight-loss drugs?

There is a distinct lack of clear information on weight-loss drug prescriptions in Australia.

Prescriptions for GLP-1 type drugs can only be claimed as part of the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) if they are used to treat diabetes. Neither Novo Nordisk or Eli Lilly release sales data for Australian markets, and pharmacies are not required to release any information regarding script volumes.

In Australia, since 2020, an extra four million scripts for drugs within the “alimentary tract and metabolism” category, have been dispensed per year for diabetes patients according to PBS data. A significant increase when compared with other drug categories.

Anecdotally, the evidence of widespread use of injectable appetite suppressants is strong, with one company reporting revenue of more than $100 million from its weight loss services over the past 18 months.

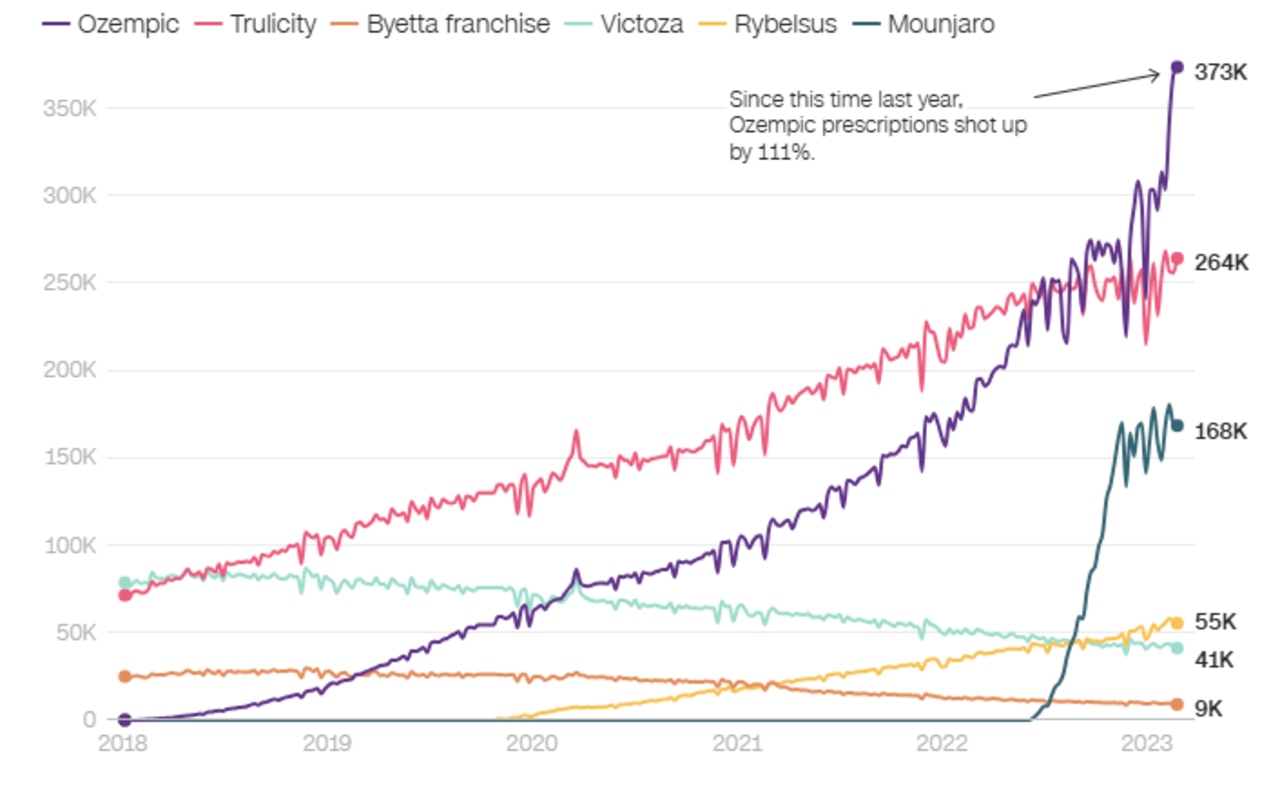

Celebrity and influencer endorsements have made weight-loss products hugely popular in the US market. According to a research letter published in JAMA Health Forum, prescriptions fills in the US for semaglutide have increased by 442 per cent from 2021 to 2023.

More than 70 per cent of these prescriptions were for Ozempic. However, since its approval for weight-loss treatment in the US in mid-2021, Wegovy fills increased by 1,361 per cent from 2021 to 2023.

JP Morgan forecasts suggest the market for obesity drugs will exceed $150 billion by 2030, with senior analyst Chris Schott indicating that, “Overall, total GLP-1 users in the US may number 30 million by 2030 – or around 9 per cent of the population.

Why is it hard to come by?

Due to skyrocketing global demand of off-label use, supply of Ozempic in Australia is severely limited with the TGA predicting that “supply will remain limited for the rest of 2024.”

However, the $730 billion Danish pharmaceutical giant Novo Nordisk quelled fears of a shortfall in supply in semaglutide-based GLP-1 drugs, with the introduction of Wegovy to the Australian market.

While Ozempic is only approved for T2 diabetes patients, Wegovy has been approved by the TGA for weight loss management. The drug is not currently covered under the PBS, with a single dose costing an eye-watering $460.

Chair of RACGP Specific Interests – Diabetes Dr Gary Deed has questioned “why there appears to be ample supply for Wegovy, the same ingredient, but the Ozempic supply remains compromised until further notice?”

Further tightening the supply of drugs like Ozempic and Mounjaro, the Albanese government earlier this year announced a crackdown on compounded replicas of the weight loss drugs.

Australian law allows pharmacists to create personalised medicines for individual patients where there is no suitable commercially manufactured product available.

“Compounded GLP-1RA products are not identical to the TGA-approved products Ozempic (semaglutide) or Mounjaro (tirazapeptide),” Health Minister Mark Butler said.

“Unlike TGA-approved products, pharmacy-compounded products are not clinically evaluated by the independent regulator for safety, quality or efficacy.”

The government estimates that at least 20,000 Australians were injecting these compounded replica products, the majority for the purpose of weight loss management.

Is Ozempic the future?

Obesity isn’t going anywhere.

The most recent figures indicate 32 per cent of the adult population in Australia are obese, a 14 per cent increase since 1995. In the US an estimated 40 per cent of adults now have obesity according to Mirova, a US-based asset management firm.

“Of the 764 million people living with obesity globally, only 2 per cent are medically treated today,” Mirova financial analyst John Boyle said.

Currently the primary barrier to access is price. With Wegovy setting customers back $460 a dose, and Mounjaro coming in between $315-$645 per month, access is restricted to those with means.

But with the Biden administration in its final weeks floating the inclusion of weight-loss drugs like Wegovy in their Medicare and Medicaid schemes, there may be a precedent for Australia to follow.

“It’s a game changer for Americans who can’t afford these drugs otherwise,” US Health and Human Services Secretary Xavier Becerra said.

The likelihood of the policy passing through congress is unclear. It could cost taxpayers up to US$35 billion over the next decade. Additionally, Robert F Kennedy, Trump’s nominee for Health Secretary has railed against the drug’s popularity.

Regardless, it is an interesting move and represents a first step towards recognising obesity as a disease, and acknowledging that it can be treated with the help of drugs.

Originally published as Weight-loss drugs are everywhere, but how many Aussies are actually taking them?