Video claims to show Chinese police forcing a person into a van due to virus fears

A video claiming to show a group of Chinese police forcing a person into a van who is suspected of having the coronavirus has emerged online.

A video has emerged claiming to show a group of Chinese police officers forcing a struggling person into a van over coronavirus fears.

The footage was shared to Twitter by Steve Hanke, a professor of Applied Economics at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland.

He claimed the video showed police capturing a person off the street due to concerns they had the deadly coronavirus.

“Chinese police forcefully capture people from the street who potentially have the coronavirus,” Professor Hanke wrote.

“The communist gov’ts censorship and lies have simply made a bad situation worse.”

The footage shows five people dressed in white, hazmat suits and face masks appearing to try and shove a person into a van.

The person can be heard yelling as they struggle against the group before eventually being forced into the vehicle.

It unclear exactly where the video was filmed.

The video has been viewed more than a million times, with social media users horrified by the footage.

“A public health crisis is evolving into an humanitarian crisis,” one person said.

“After being stuffed in a van with possibly contaminated people, he’s sure to have it now,” another said.

One person wrote: “Looks like scenes from a horror movie.”

China’s police have recently been called out by the country’s top court for a too-harsh crackdown on online rumours about the virus outbreak.

The coronavirus has been likened to Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS), which China experienced an outbreak of in 2002 and 2003.

The spread of this new infection has now surpassed the global reach of the SARS outbreak.

Authorities suspect the disease originated in a seafood market that sold live animals in the central city of Wuhan, and told the World Health Organisation about the new virus on the last day of 2019.

A day later, eight people were detained by police after claiming online that Wuhan was in the grip of a fresh SARS outbreak.

The group were punished for “publishing or forwarding false information on the internet without verification”, a police statement at the time said.

But the country’s Supreme Court lashed out last week at the police over the incident, with judge Tang Xinghua saying while the information might not have been accurate, the people involved did not deserve to be punished.

“If the public had believed these ‘rumours’ at the time, and carried out measures like wearing masks, strictly disinfecting and avoiding wildlife markets … it might have been a good thing,” he said.

Tang said the indiscriminate crackdown on online rumours could have “become negative textbook material for weakening public trust in the government” or a “vicious event” eroding support for the Communist party.

China has instituted the largest quarantine in human history, locking down more than 50 million people in the centre of the country.

Those who have recently been to Wuhan are being tracked, monitored, turned away from hotels and placed into isolation at their homes and in makeshift quarantine facilities.

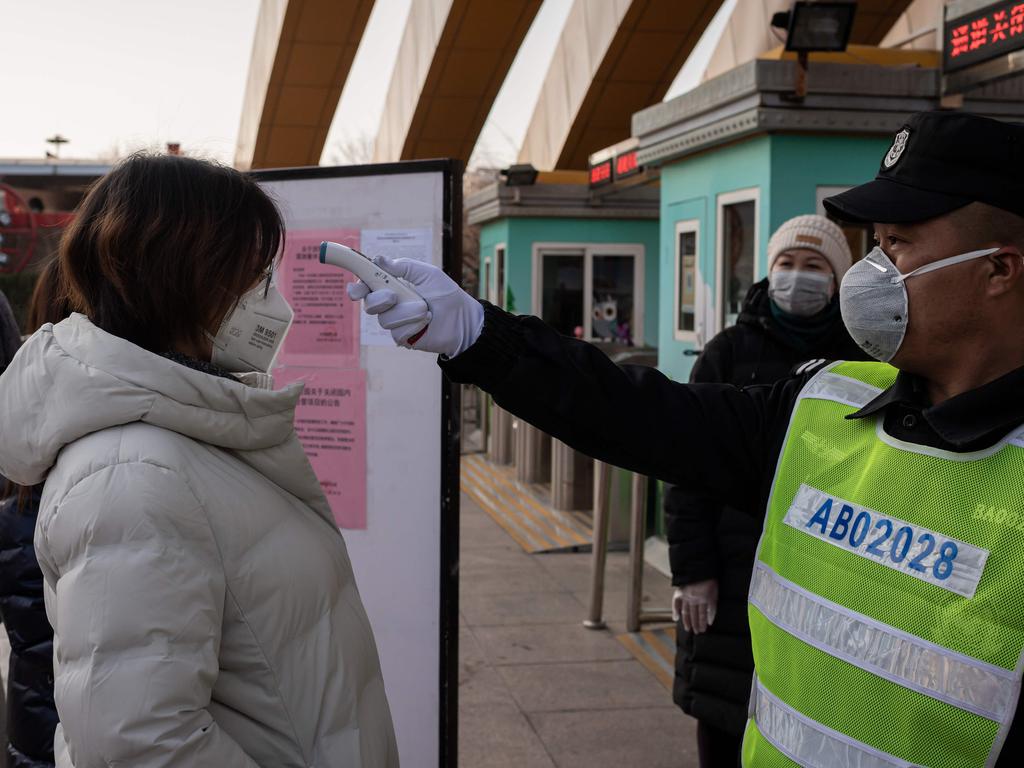

Residents from Hubei province also receive daily phone calls and can be made to have their temperature checked up to three times a day.

During the past decade, the Chinese government crafted a rigorous system of social control, which it calls “stability maintenance.”

Through both high and low tech methods that range from face-scanning cameras to neighbourhood informants and household registration, Beijing keeps track of its 1.4 billion citizens, managing them via community-level officials.

Since the virus outbreak millions of local officials have been mobilised to monitor, screen and warn – and restrict, to varying degrees – in a governance approach that Beijing calls “blanket-style tracking.”

“We must effectively manage people from Wuhan according to the principles of ‘tracking people, registering them, community management, inspecting them at their door, mass transfers, treat abnormalities,”’ Li Bin, deputy director of the Chinese National Health Commission, said at a news conference.

-With AP