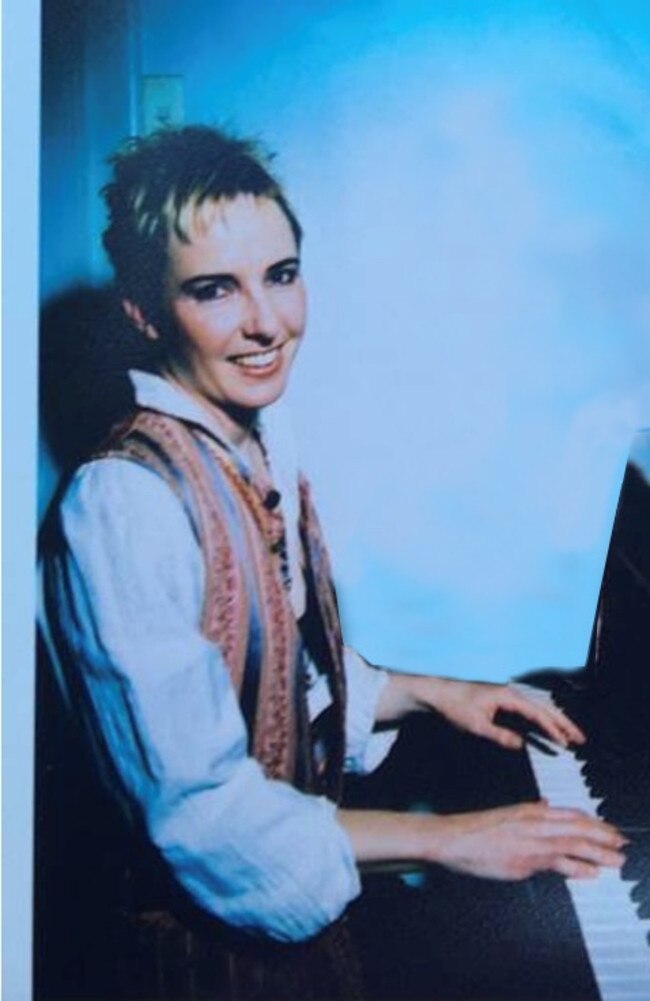

Life-altering brain injury leaves woman unable to walk and talk at the same time

Claire Cooper was a pianist but a horrific car crash changed her life forever. Now she can’t let her mind wander even while swimming as she starts inhaling water.

Prior to her accident, Claire Cooper was like any busy multi-tasking woman. But nowadays she can’t even walk and talk at the same time.

Ms Cooper, 58, used to be a classical pianist before a life-changing accident nine years ago, which happened while she was cycling to work at Melbourne University. While in a separated bike lane she was hit by a car whose driver - talking on the phone at the time - ran a red light.

The Victorian doesn’t remember what happened on that day, or in the two months prior to the accident, or the three months after it.

She was in a coma for about three weeks and in hospital for about four months in total. Her earliest memories of that time are of being in hospital and complaining about her feeding tube, as well as getting a day pass to go home.

“I have lost about five months in memory, I don’t remember waking up,” Ms Cooper told news.com.au.

The accident left her with six broken ribs, a collapsed lung, torn tendon in her shoulder, and a shattered pelvis that had to be reconstructed using three pins and a metal plate.

A brain injury also left her with spasticity in her entire right side, which impacts her tongue and “is why I sound pi**ed all the time”.

After waking up, Ms Cooper had double vision initially and had to learn to walk and talk again. She used to fall over a lot initially because she had balance problems as well as spasticity in her leg. She also can’t do two things at once anymore because if her mind wanders, she will be unable to complete what she’s doing.

“Even now with basic things I really have to concentrate,” she said.

“I had to teach myself to swim again and breathe underwater. If I’m swimming and I think of something else, I inhale water.”

Nine years after her accident, it still takes Ms Cooper five times longer than previously to complete basic tasks. Even pouring water into a kettle can go wrong if she starts thinking about something else.

“I need to concentrate — I was always a fast multi-tasking person but not any more,” she said.

“With the brain injury I also get fatigued so I spend half the day on the couch recovering from doing basic things, it’s affected my life in every way you can imagine.”

Her emotional control has also been impacted and Ms Cooper now has a tendency to laugh at times when she’s nervous or uncomfortable. At her father’s funeral, Ms Cooper sat at the back of the church instead of with her family at the front, because she wasn’t sure if this would be an issue.

“In the end it was fine but you just never know,” she said.

Interestingly, Ms Cooper’s ability to sight read music was not impacted by her accident, which she describes as “extraordinary”, although she can no longer work as a classical pianist.

Her playing now sounds like “sh*t” but Ms Cooper still enjoys practising and gradually getting better.

“I reckon in another 30 years I’ll play at the level of a 10-year-old,” she said.

Her accident also made her realise the “inherent snobbery” with which musicians were treated.

“When you are a musician people assume stuff about you, about your intelligence, your capacity or something,” she said.

But after her brain injury Ms Cooper said she thought people often thought she was a bit stupid, especially if they heard her slurring her words.

“There is an inherent snobbery about how people treat musicians which I hadn’t realised,” she said.

However, being so close to death has changed her outlook.

“It makes you worry less about the small things, I don’t give a sh*t what people think about me — although that could also be because I’m 58 years old now too,” she said.

Importantly, Ms Cooper believes her piano training has helped her to appreciate the tiny incremental improvements she’s made through repetition and practice.

“I’m still finding improvements even after nine years, but you have to practice just like you do with piano — and I still do practice piano which is fantastic brain work.”

Ms Cooper will address the National Brain Injury Conference in Sydney this month through Zoom and says her message is that people can get better.

“Improvement is possible and I think this sense of hope is really important,” she said.

It’s been estimated that more than one in three people will suffer from a brain injury in their lifetime, while one in 10 will suffer a life-changing injury.

After suffering a brain injury herself, Ms Cooper has realised how many others around her who are also dealing with the condition.

She also believes finding the right treatment helps as each brain injury can be different so shouldn’t be treated with a one-size-fits-all plan.

“I understand why they do it but it doesn’t always work and it has taken me a long time to figure out what works for me,” she said.

“It’s kind of weird at 49 years old to have to learn all this stuff again but the thing about improvement is you’ve got to keep working at it,” she said.

“It’s not going to happen by itself but if you work at it, it does keep improving and I think that this is a really important message.”