How serious coronavirus outbreak would change your everyday life

Authorities have enacted Phase Two of a coronavirus response plan, warning a serious outbreak will impact everyday life for millions of people.

Coronavirus is in Australia and it’s no longer in people who contracted the deadly infectious disease overseas, with the first human-to-human cases confirmed yesterday.

Australia’s chief medical officer, Professor Brendan Murphy, said an outbreak in Australia was now likely, stating “it’s no longer possible to absolutely prevent new cases coming in”.

As cases increase and the risk grows, authorities have warned they will implement a range of sweeping measures in a bid to slow the spread.

A vaccine is at least 12 months away and probably closer to 18 months, plus the arrival of cooler months and cold and flu season will intensify the risk of coronavirus spreading.

As the situation worsens, the everyday lives of millions of Australians will inevitably be impacted.

DEATH AND SERIOUS ILLNESS

What a serious outbreak of coronavirus in Australia might look like is difficult to predict, given modelling is based on what’s occurred in China.

Things here are vastly different, from the quality of the healthcare system to the robustness of hygiene and sanitation practices.

However, a sustained and significant period of transmission in Australia could result in 25 per cent of the population becoming infected over the duration of the crisis, on the low end of estimates, and as high as 70 per cent in a worst-case scenario, Professor Raina MacIntyre, head of the Biosecurity Program at the Kirby Institute at the University of NSW said.

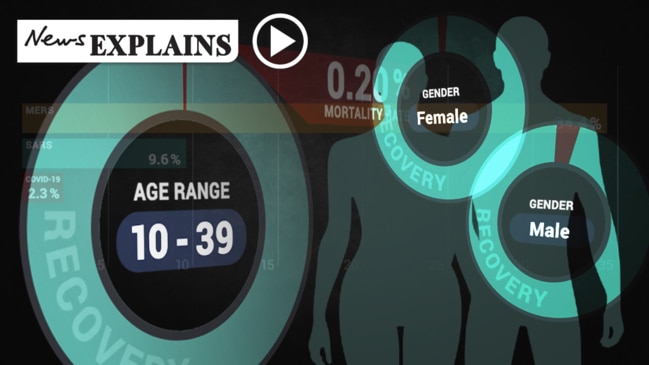

“So, a case fatality rate of 2 to 3 per cent is high (in that context),” Prof MacIntyre said.

RELATED: Spate of new coronavirus deaths in the United States announced

A mortality rate of 3 per cent has been calculated by the World Health Organisation and again applies to China and is likely closer to 1 per cent in the developed world.

But looking at the modelling, in the mid-range of that estimate – 50 per cent of Australians contracting coronavirus – Prof MacIntyre said it could cause as many as 400,000 deaths.

Professor Nigel McMillan, infectious diseases director at the Menzies Health Institute of Queensland at Griffith University, said the deadliness of the disease in Australia was difficult to anticipate.

“For pandemic planning, we can use models, but right now most are inaccurate as we don’t know two important things – how many people get infected, the infection attack rate, and how many get sick, the clinical attack rate,” Prof McMillan said.

“That is, we suspect there are a large number of people who aren’t identified as having COVID-19 because they have a mild cold. We can make guesses, but it will take time to get this information.”

That said, the mortality rate “hasn’t really changed much over time”.

RELATED: Get the very latest updates on the coronavirus

MOVING TO PHASE TWO

Prime Minister Scott Morrison last week activated the country’s emergency response plan for pandemics, which outlines three different phases of dealing with infectious disease crises.

Phase One was focused on border control measures and social distancing in order to slow the introduction of the disease into Australia.

In an article for The Conversation, University of Melbourne’s Doherty Epidemiology director Jodie McVernon said it was a case of “when local transmission occurs, not if”.

And yesterday, that dangerous new development was confirmed with the first human-to-human infection in Sydney involving a doctor who treated a patient with coronavirus.

In a second case, the sister of a man who arrived in Australia from Iran on Sunday contracted the disease.

These instances up the ante when it comes to battling coronavirus.

Enacting Phase Two would involve disruptions to everyday life, Prof McVernon said, and will now come into effect.

“The focus will shift to minimising spread within Australia and limiting the health, social and economic impact of the disease,” she said.

“This could include (the) cancellation of large local gatherings, sporting matches and festivals, closure of schools, universities and some workplaces, and strict local travel restrictions.”

Other areas where Australians gather in large numbers – shopping centres, cinemas, theatres, beaches and parks – could also be shut down, and in extreme cases, the free movement of people on public transport could be restricted.

The government’s response plan was designed to be flexible, allowing authorities to adapt public health policies depending on new developments, Prof Murphy said.

“One of the things we would be very focused on if we got an outbreak is trying to slow the pace of development by containing cases, because a slowly evolving outbreak has much less pressure on the system, even though it might have a longer impact,” Prof Murphy said.

“If you had an outbreak in a particular city or state, if it got to a certain size you might close the schools or change the configuration of the hospitals to deal with that.

“If it’s in several cities or states, you do it according to the local needs at the time. What we’ve learned from repeated flu pandemics is you have to adapt the response according to the circumstances almost on a daily basis.”

Yesterday, Attorney-General Christian Porter warned Australians that certain powers would become necessary in the months ahead.

COVID-19 has been listed as a human disease so that authorities can enact the Biosecurity Act, Mr Porter said.

“There are two broad ranges of powers that people may well experience for the first time,” he said.

“There is the ability of the government to impose – always based on medical advice, but nevertheless impose – a human biosecurity control order on person or persons who have been exposed to the disease.

“It could require any Australian to give information about people that they’ve contacted or had contact with so that we can trace transmission pathways. It will also mean that Australians could be directed to remain at a particular place or indeed undergo decontamination.

“Secondly, a very important power that may be experienced for the first time, and that we will be monitoring very carefully, is the declaration of a human health response zone.”

RELATED: Should you cancel your international travel?

Health Minister Greg Hunt described the approach as being like “rings of containment”, where infected individuals and their families or affected groups could be quarantined.

Protecting Australian society in the event of a widespread outbreak “must come before individual rights”, Prof MacIntyre said.

“We need to weigh up the balance between individual freedom and rights versus the public good, and infectious diseases epidemics pose a unique risk because of contagion.”

HEALTH SYSTEM STRAIN

In addition to potential deaths from coronavirus, dealing with a high volume of infections would place incredible stress on Australia’s health system.

“In China, we know that in addition to the people who died, 5 per cent needed to be in (intensive) and 14 per cent needed a hospital bed,” Prof MacIntyre said.

Again, on the modelling of a 50 per cent infection rate of the population, that could be as many as two million people needing hospitalisation and 650,000 patients needing an intensive care unit bed.

“These are total numbers over the whole epidemic, which may last one year,” she said.

“In Sydney, we estimate there are about 16,000 public hospital beds and 6000 private hospital beds.

“We have previously modelled the number of daily beds required in an epidemic scenario for a different infection, which shows that capacity for beds could be rapidly exhausted in a severe epidemic.”

RELATED: Six key facts experts want you to know about the coronavirus

Prof McMillan said health authorities would prepare for a large influx of patients at hospitals and undertake other measures, such as stockpiling antivirals, some of which appear to slow the virus.

“They (will also need to be) advising the public that when the time comes they will need to think about things like stay at home if ill, social distancing, avoid large gatherings and so on,” he said.

As a result, people diagnosed with coronavirus but experiencing a mild case would be asked to “take responsibility for their own ‘social distancing’”, Prof McVernon said.

That means self-quarantining and self-isolating at home. That advice would also be extended to anyone who discovered they’ve come in close contact with someone with the disease.

“These measures, while disruptive to individuals and households, have been highly effective to date in preventing community transmission of COVID-19 in Australia and will remain very important throughout the response to this disease,” Prof McVernon said.

But Prof MacIntyre said this method was less reliable and difficult to co-ordinate and monitor.

“People would also have to be relied on for voluntary self-quarantine in this situation, and there is a risk some may break quarantine,” she said.

More broadly, an influx of people seeking treatment at hospitals would see all non-essential patients diverted and elective surgeries deferred.

Victorian Premier Daniel Andrews acknowledged today the inconvenience and distress this may cause those awaiting non-emergency surgeries, but said it was the most appropriate measure.

ECONOMIC PAIN

An outbreak of the coronavirus in Australia would have more serious consequences for the economy across the board.

It’s already being felt. The share market is down, the tourism sector is hurting and universities are bracing for millions of dollars in losses.

Expect that to get much worse if people panic, Professor Warren Hogan of the University of Technology Sydney said.

“The key economic challenge will be to stop a vicious cycle of weaker spending and job losses taking hold,” Prof Hogan wrote in an article for The Conversation.

Australia’s economic reliance on China means warnings of the superpower facing a recession due to travel and trade restrictions will hurt.

“Estimates of the impact of the containment policies on Chinese growth in the first quarter of the year range from minus 2 per cent to minus 10 per cent, enough to obliterate growth in the world’s fastest-growing big economy,” Prof Hogan said.

At the weekend, forecasts surrounding China’s manufacturing and service sectors were dire, he said, and “few countries are as exposed” to the impacts of that as Australia.

All of this on top of an already problematic set of economic circumstances – gross domestic product figures for the first three months of 2020 to be released tomorrow are unlikely to be rosy – also points to the possibility of a recession here.

“It will leave Australia exposed to what is known as a technical recession – two consecutive quarters of negative economic growth, in the three months to March and the three months to June,” Prof Hogan said.

“This possibility, Australia’s first recession in 29 years, will depend on how we react to the emergence of coronavirus onshore.”