How bad will coronavirus outbreak get?

It’s been making headlines for weeks – now experts have revealed just how bad the deadly Covid-19 coronavirus outbreak is likely to get.

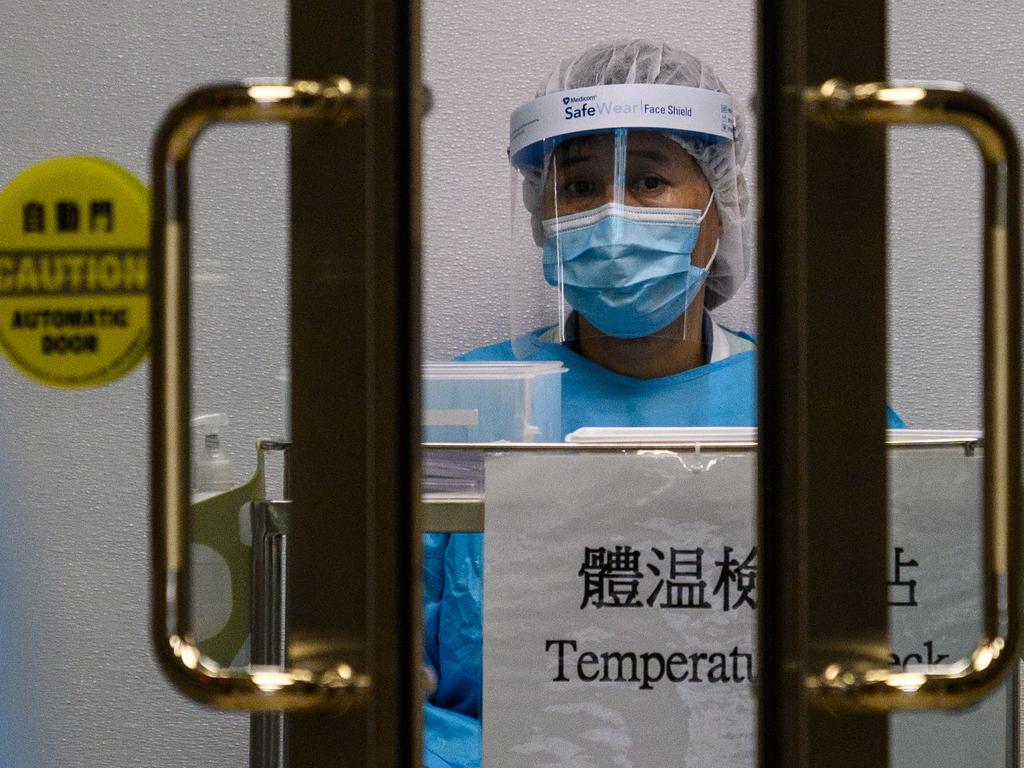

As the world prepares for coronavirus to officially reach “pandemic” levels, health systems across the globe are preparing for the worst.

The Centres for Disease Control (CDC) has announced it is initiating preparations for a “likely” spread of Covid-19 in the United States.

“We are reviewing all of our pandemic preparedness materials and adapting them to Covid-19,” an official told media.

Victoria’s Chief Health Officer Brett Sutton has responded in kind.

“It’s clear that with local transmission in several countries that a pandemic is very likely, if not inevitable,” his official Twitter account reads. “We are working rapidly on planning and surge with our health sector.”

A new assessment by the Imperial College London warns the outbreak is likely dramatically worse than believed:

“We estimated that about two-thirds of Covid-19 cases exported from mainland China have remained undetected worldwide, potentially resulting in multiple chains of as yet undetected human-to-human transmission outside mainland China.”

This is sending shockwaves through international health circles.

“In sum, many countries likely be dealing with a Covid epidemic soon,” responded the director of the Johns Hopkins Centre for Health Security in Baltimore, Tom Inglesby. “They should be quickly preparing to deal, to do best they can with medical care, work to blunt (its) overall impact, protect health care workers, keep health care system functioning safely and communicate clearly to the public.”

Risk group Lanard and Sandman say it’s important to point out that, while it looks like Covid-19 will go global, we don’t yet know how severe the disease is.

But, they add, the most “crucial (and overdue) risk communication task for the next few days” is to prepare the public for when the ‘keeping it out’ – containment – approach fails.

In other words, get ready for quarantine lockdowns.

RELATED: Containment fails as virus goes global

RELATED: Chinese leader’s virus concession

‘TAKE THE RISK OF SCARING PEOPLE’

“In most countries – including our United States and your Australia – ordinary citizens have not been asked to prepare,” Lanard and Sandman write. “Instead, they have been led to expect that their governments will keep the virus from their doors.”

But such expectations are set to backfire.

And the risk assessors warn concerned academics and medicos to stand resolute in the face of accusations of ‘fear-mongering’.

“Take the risk of scaring people … It is better to get through this OMG moment now rather than later,” they write.

“Respond that hiding your strong professional opinion about this pandemic-to-be would be immoral, or not in keeping with your commitment to transparency, or unforgivably unprofessional, or derelict in your duty to warn, or whatever feels truest in your heart.

“You’re only darned if you warn about something that turns out minor,” Lanard and Sandman write. “But you’re damned, and rightly so, if you fail to warn about something that turns out serious.”

Australian National University infectious disease specialist Dr Sanjaya Senanayake agrees it is time to get prepared. But not to panic.

“Even though we don’t know at this point whether or not a pandemic will occur, governments should be prepared for one and send out reassuring messages to the public,” he told News Corp last night.

He says indications are it will be a disruptive disease. But not devastating.

“While a lot isn’t known about this virus, at this stage it appears to cause mild illness in the majority of people with a low case fatality rate. So while it will cause disruption for a time to health services and economies, they will eventually recover as more and more people become immune.”

RELATED: Don’t buy China’s coronavirus story

RELATED: Scary development in virus spread

CHANGING TACTICS

The director of the Center for Communicable Disease Dynamics at Harvard University, Marc Lipsitch, says containment no longer appears to be an option.

Instead, countermeasures must be identified and implemented.

“Most things we can do to slow the virus’s spread – isolation, quarantine, social distancing, cancelling public gatherings, treating cases with antivirals – are temporary,” he wrote. “Once let up, transmission can resurge.”

When a disease is established in a community, international travel bans become pointless. Instead of slowing its spread, it makes it harder to bring in urgently needed supplies and support.

So, Lanard and Sandman write, public health messages must switch from “stopping them from infecting us” to “keeping us from infecting each other”.

That means cancelling mass events, considering school closures – and preparing for community lockdowns.

“We are near-certain that the desperate-sounding last-ditch containment messaging of recent days is contributing to a massive global misperception about the near-term future,” they write.

To counter this, public health officials should be talking about slowing the spread of the virus. Not stopping it.

“One horrible effect of this continued ‘stop the pandemic’ daydream masquerading as a policy goal (is that) it is driving counter-productive and outrage-inducing measures by many countries against travellers,” they write. “But possibly more horrible: The messaging is driving resources toward ‘stopping,’ and away from the main potential benefit of containment – slowing the spread of the pandemic and thereby buying a little more time to prepare for what’s coming.”

BUYING TIME

Lipsitch says slowing Covid-19’s spread will be difficult. Strict quarantine measures worked well for SARS in 2003 because isolating sick individuals prevented the disease from spreading.

Not so now.

“For Covid-19 it seems clear from individual well-documented cases that people can transmit before symptoms (become distinctive),” he wrote. “The key question – for which we (desperately) need good data – is whether this is common or rare. Some circumstantial evidence suggests it could be common.”

This limits the effectiveness of regular medical interventions. So practices such as social distancing (self-isolation), as well as “quarantine or lockdown” must be considered.

Slowing the spread of a virus through the community causes an epidemic to last longer – but with less ‘peak strain’ on health facilities.

“That is beneficial because: 1) fewer individuals get infected in total; 2) the burden on the health system is spread out, with lower peak demand for scarce resources; 3) we will know more as time goes on about how to care for patients, so it is better to get it late than early; 4) if we can spread it out enough there may be new drugs, vaccines, or other countermeasures to aid in preventing and treating infection.

“Summary: Delay is good.”

Another essential piece of unknown information is how the virus affects children.

So far, they seem strangely immune to Covid-19’s symptoms.

But are they innocent carriers?

“If kids are important for transmission, school closures may help; if not, less so,” Lipsitch writes.

And the delaying tactics are already producing results.

“Although a vaccine program is many months away, there are promising therapeutic options for treating people with the virus,” Dr Senanayake says.