Gaëtan Dugas, the man accused of being a ‘monster’ all because of a confusion between a number and a letter

The handsome Canadian was charming. But he would become known as a “monster” all because of the confusion between a number and a letter.

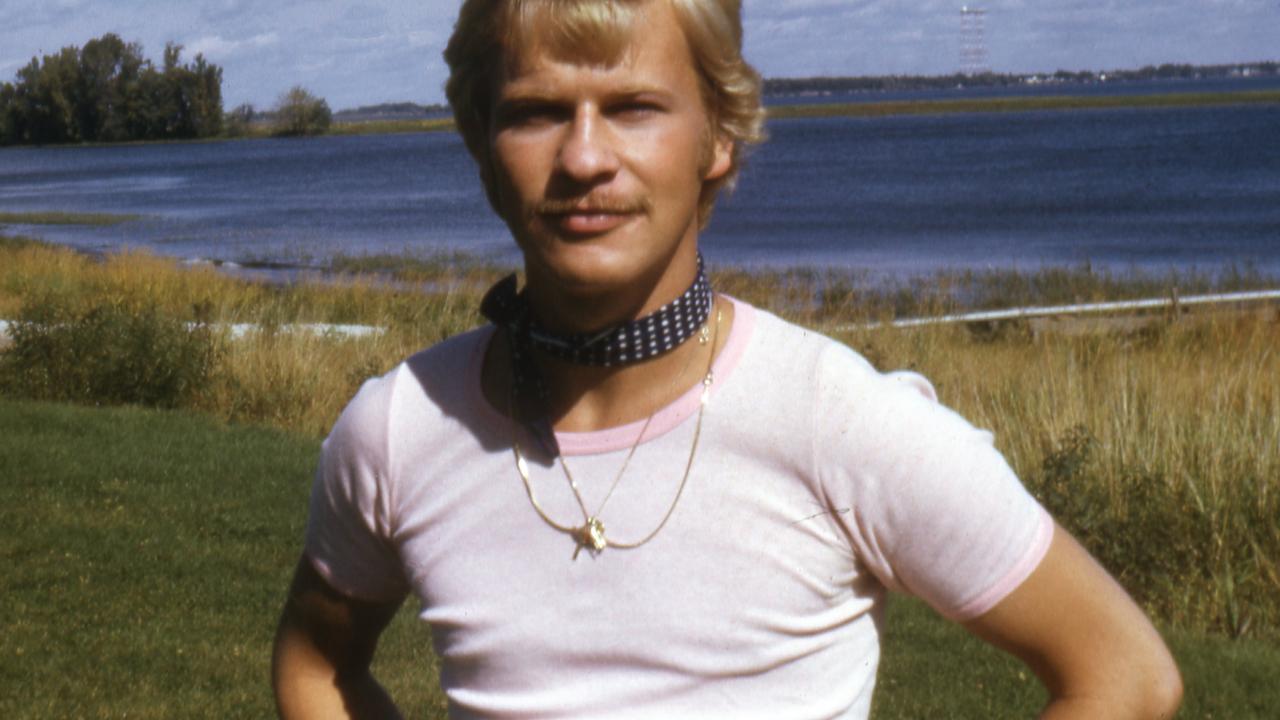

Gaëtan Dugas was everyone’s friend. Handsome, funny, full of life. Those who knew the Canadian said he was convinced one day he would become a star.

And he did become famous. But for all the wrong reasons.

In 1987, three years after his death, Dugas’ face was plastered across the US and beyond. He was identified as “patient zero” — the villain behind an epidemic that would lead to the deaths of 700,000 people.

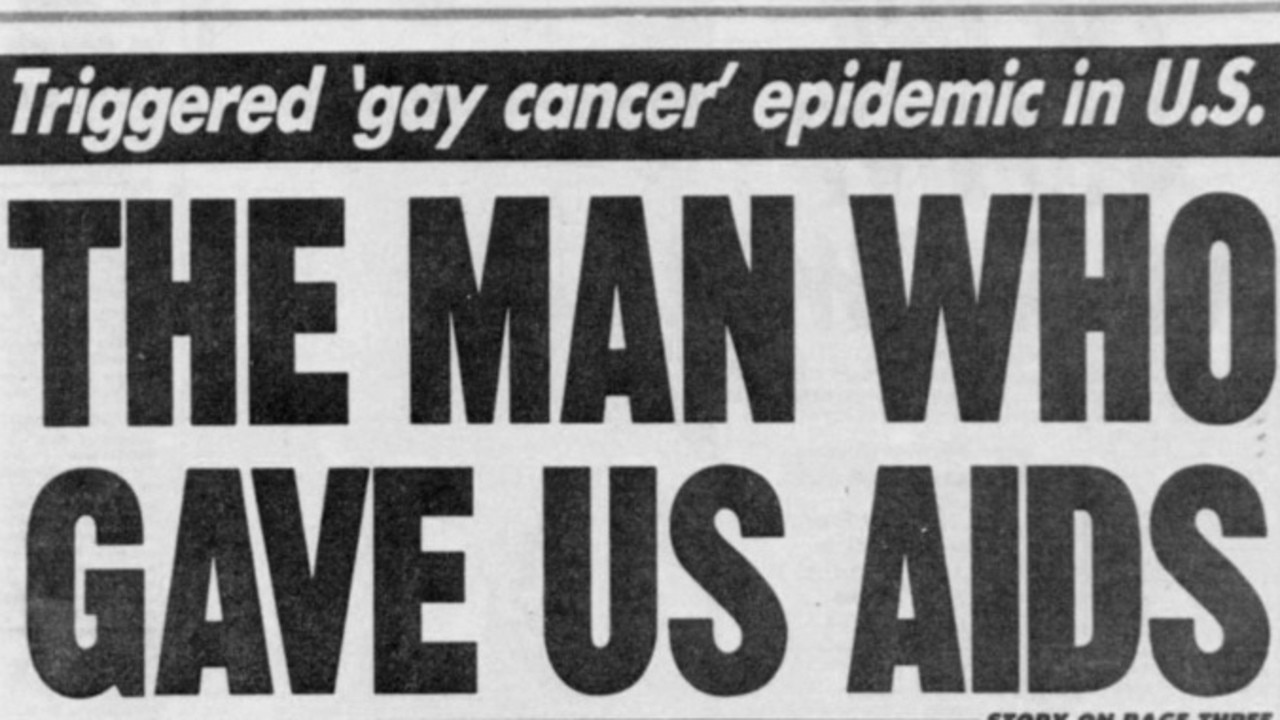

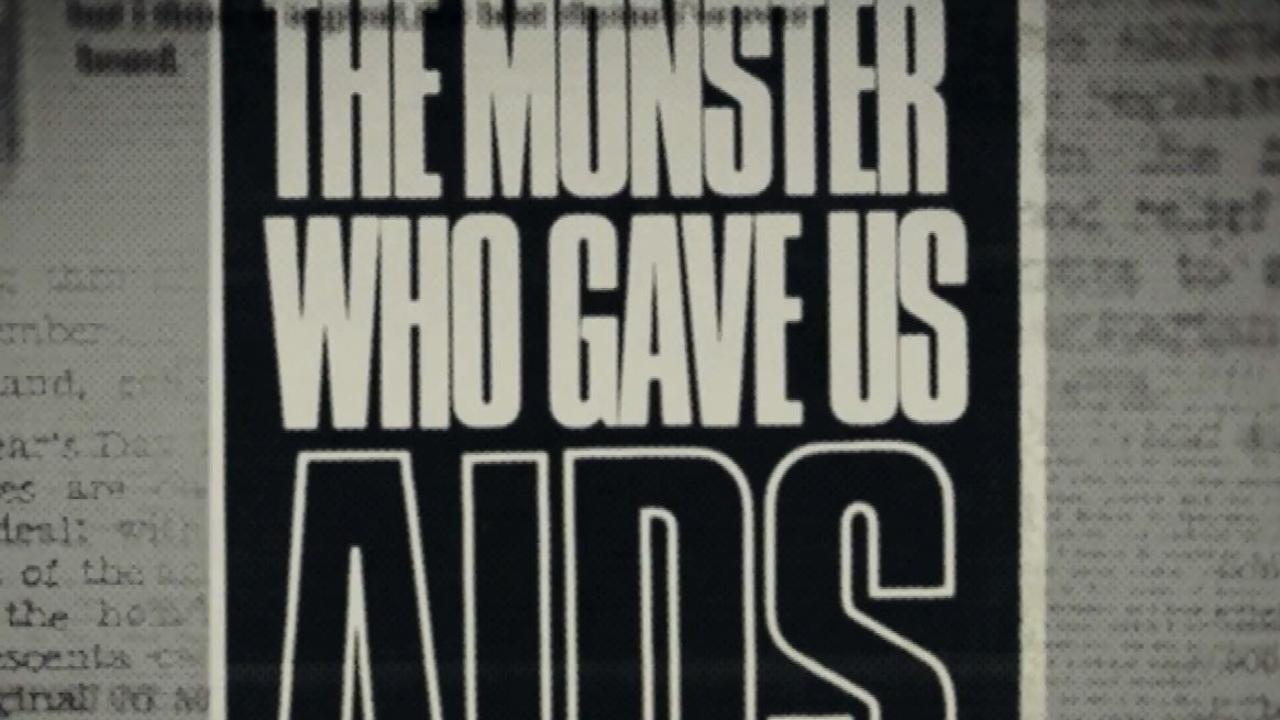

One infamous headline declared Dugas “the monster who gave us AIDS”.

Dugas’ name became so synonymous with the epidemic, one friend said some people imagined him to be “eight-foot-tall, dripping blood”.

Modern medicines mean few people who have HIV, at least in the developed world, will ever go onto develop AIDS, the condition’s fatal end stage. That wasn’t the case in the 1980s.

In the panic surrounding AIDS, Dugas was an easy bogeyman.

He was flamboyant; refused to hide his sexuality and made no apologies about his sex life, sleeping with as many as 250 men a year.

Single-handedly it seemed, this affable flight attendant had been the catalyst for spreading HIV across North America. He was labelled the “Columbus of AIDS”.

Except that was never the case.

Dugas was condemned because of a bizarre combination of factors. The most inexplicable of which was due to a simple typo, an innocuous mix-up between a number and a letter.

Then there was his distinctive French-Canadian accent and name and the fact he gave so much information to health authorities.

“That is one of the great ironies — had he not been so helpful and co-operative none of this would have happened,” filmmaker Laurie Lynd told news.com.au from Toronto.

Mr Lynd is the writer and director of Killing Patient Zero, a film about Dugas that will be screened as part of this month’s Sydney QueerScreen film festival.

In the documentary, Dugas is remembered by friends and colleague as being “charming”, “lots of fun” and “an outrageous gay guy” who didn’t give a stuff what other people thought of his life.

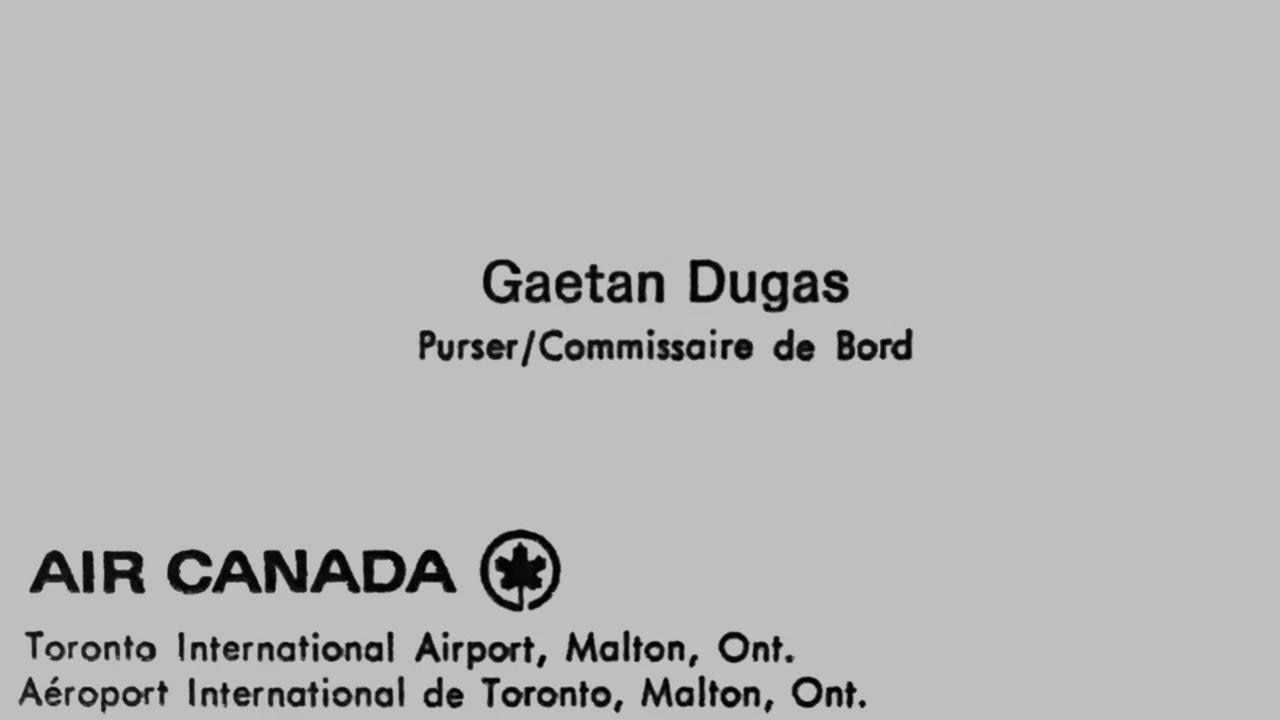

Flying for Air Canada in the late 1970s and early ‘80s, Dugas had even been known to slip good-looking passengers his business card in case they wanted to hook up later.

And hook up he did, with hundreds of partners a year.

Mr Lynd said it was easy to be judgmental, but homosexuality was only gradually being decriminalised in the US. It had just been struck off a list of mental disorders and no one knew AIDS even existed.

“It was a gay candy store; an explosion of sexuality. Gaëtan was having a good time.

“And then just as gay liberation happened, AIDS hit and it was catastrophic,” Mr Lynd said.

Doctors first began to notice clusters of gay men falling ill with a “gay cancer” in California and New York in 1981. The US Centres for Disease Control (CDC) interviewed some of those men to see if they could work out what was happening.

One said he had had sex with a flight attendant with an accent; another produced Dugas’ business card.

PATIENT ZERO

The CDC contacted Dugas who was an open book to researchers. He allowed them to take vials of his blood and gave them names of his sexual partners.

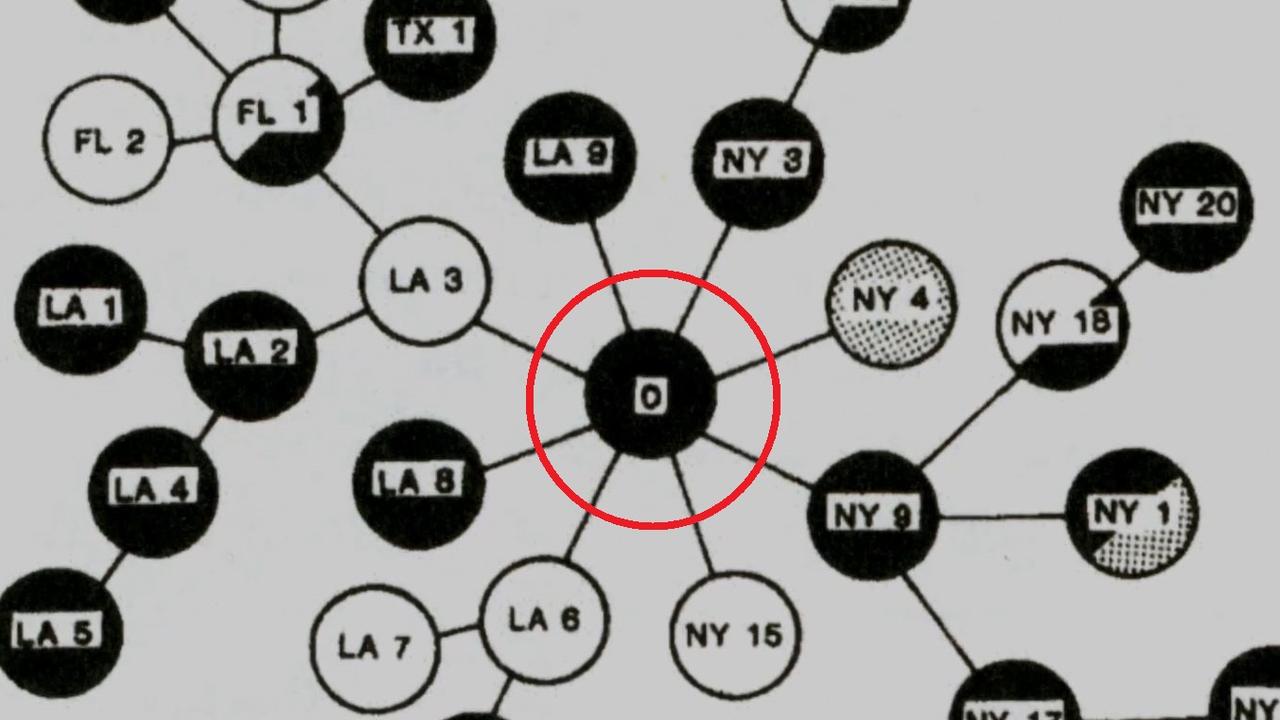

In the CDC’s notes, he was listed as “patient 57” and later as the “out of California” case because he lived away from the state.

His willingness to help the researchers, unlike many other gay men who were suspicious of the authorities, helped build a picture of how HIV was spreading.

Dugas continued having sex, even after fears of the gay cancer — that would later become known as HIV/AIDS — rattled the community. But at the time there was still no conclusive proof it was passed through sexual intercourse, and many gay men had a fatalistic view assuming it would get them eventually no matter what measures they took.

In 1984, Dugas became one of the 700,000 North Americans who would perish from an AIDS-related illness.

And there his story may have ended but for US journalist Randy Shilts.

In 1987, he published the best-selling book And the Band Played On. It was one of the seminal works on HIV and helped shame the US Government into properly funding research.

Tucked away in the book were a few pages on a so-called “patient zero” to illustrate how the virus could spread. Shilts named patient zero as Dugas.

The media erupted: Dugas’ face was everywhere — this patient zero who was the ground zero of the crisis. He was characterised as a kind of “typhoid Mary” callously spreading the virus.

Commentators went far beyond what was even in the book and surmised Dugas had been singularly responsible for first bringing HIV to the Americas and then from coast to coast.

TYPO

But there was never a “patient zero”. It was a typo; a mix-up in some medical papers that Shilts then republished.

The CDC’s original research, released several years previously, included information from Dugas. But, like others, he was identified only as an unnamed “patient” followed by a number or letter or combination of both.

In the documentary, William Darrow, who was part of the CDC’s AIDS Task Force at the time, recalled his surprise when fellow researchers began mentioning a “patient zero”.

“Who are you talking about?” he asked a colleague.

“C’mon Darrow, you’re the one that told us about him,” came the reply.

Astonished, Mr Darrow twigged what had happened: “I told you about patient O, the ‘out of California’ case.”

“Oh, that was an O?” the researcher said. “We thought it was a zero.”

But by then the idea of a patient zero had stuck.

Later, it was Shilts who correctly deduced that the former patient 57, then patient O who incorrectly became patient 0, was Dugas.

Mr Lynd said an air steward from Quebec, infected with HIV like many others, was now seen as the epicentre of AIDS in America.

“The consequence of misreading an O as a zero can’t be underestimated.

“Much of what Shilts accomplished was heroic, but he is guilty of creating this vampiric version of Gaëtan, of twisting reality into this monster who went out deliberately infecting people, and I firmly believe that was not the case,” Mr Lynd said.

NOT THE FIRST CASE

The CDC’s work did not back up the headlines either. They examined how the virus had evolved in the population and deduced while Dugas was an early case, he wasn’t the first. Later genetic testing of his still stored blood confirmed the strain of AIDS he had was one of many.

It’s now thought the first US death from AIDS could have been back in 1969.

Further research indicated that, given the long latency period of HIV, some men who were linked to Dugas were likely to have been infected years before they met the Canadian.

“It’s a cautionary tale about the cost of prejudice and scapegoating,” Mr Lynd said.

“Unfortunately, it’s human nature that we need someone to blame.

“One of Gaëtan’s sisters said ‘so this is the thanks he gets for working with the researchers’.”

The stigma of HIV lingered on, Mr Lynd said. For years, HIV positive people were banned from travelling to the US.

FORCED HIV TESTS

ACON (AIDS Council of NSW) chief executive officer Nicholas Parkhill told news.com.au discrimination and fear was also rife in the early days of the epidemic in Australia despite the government here being more proactive leading to far fewer infections.

There were even calls for Sydney’s Mardi Gras to be banned, as if axing a parade would halt HIV in its tracks.

“Initial information suggested that gay men were to blame for the virus, and as a result, the gay community suffered greatly at the hands of public opinion,” Mr Parkhill said.

“Still, after 35 years, stigma and discrimination for people with HIV remain.”

Mr Parkhill sad 74 per cent of people with the virus had been discriminated against in the last year. And he cited recent moves by police officers to force people to take HIV tests if, for instance, they had bitten a cop. That “rails against all the evidence underpinning HIV transmission” that shows HIV cannot be passed via saliva, Mr Parkhill said.

Mr Lynd said he hoped Dugas’ reputation should be restored.

“I would like his legacy to be one of a very brave gay man who didn’t cave to prejudice and lived his life fully,” he said.

“Someone remembered for the work he did with the CDC which helped prove to the world this was a sexually transmitted disease.”

See Killing Patient Zero on September 21 during the Sydney QueerScreen film festival.