Explainer: How the Wuhan coronavirus jumped from animals to humans

Like SARS and MERS, the Wuhan outbreak evolved from coronavirus strains that previously affected only animals. Here’s how.

WARNING: CONFRONTING IMAGES

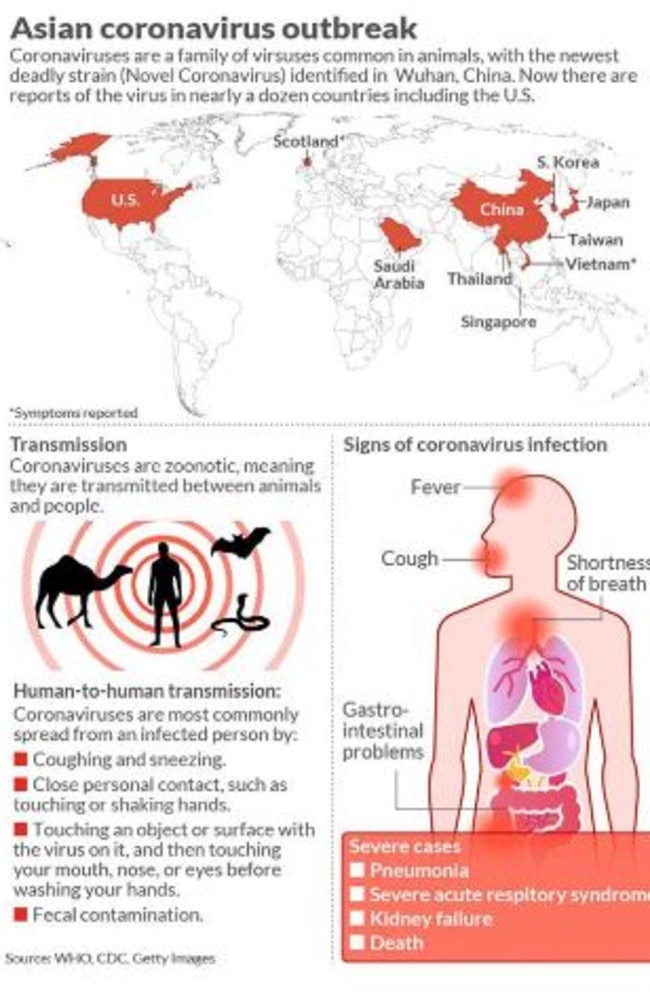

At least 10 cities home to 33 million people are in lockdown amid the spread of a new strain of coronavirus that originated in Wuhan, China, and has spread around the world.

Like the deadly SARS and MERS viruses that came before it, the Wuhan outbreak is believed to have evolved from coronavirus strains that previously only affected animals.

Novel coronavirus or 2019-nCoV, as the new strain is known, is classified as a zoonotic, meaning the first patient infected acquired the virus directly from animals.

Coronaviruses are not the only zoonotic diseases — HIV and ebola also fall into this category and biotectechnology company Gilead Sciences is conducting tests to see if an experimental ebola treatment called Remdesivir can combat 2019-nCoV.

SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome) is believed to have made a species jump from bats to humans via the intermediate host of farmed civet cats bred for human consumption, and MERS (Middle East respiratory syndrome) from bats via camels.

The exact origin of 2019-nCoV is less clear but a controversial new theory published by Chinese virologists two days ago pointed the finger at snakes, although some scientists are sceptical the virus could jump from a cold-blooded animal to a warm-blooded one.

Zhong Nanshan, a Chinese government medical adviser, also identified badgers and rats as possible sources. Beijing health officials have warned that while 2019-nCoVvirus is not as deadly as SARS, it is mutating more quickly, making it more transmissible.

HOW THE CORONAVIRUS JUMPED FROM ANIMALS TO HUMANS

Scientists have said “unnatural situations” where animals are brought together and housed in cramped, unhygienic conditions in proximity to people create opportunities for viruses to move between animals and mutate to the point they are able to infect humans.

By all accounts, the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market in Wuhan City, where the virus was first detected, fit that description to a tee, with vendors illegally trading in wild and exotic animals alongside the daily ocean catch.

Wildlife sold at the Huanan “wet” market for human consumption included wolf cubs, civet cats, bats, dogs, pigs, snakes, chickens, donkeys, badgers, bamboo rats, hedgehogs and deer. Wet markets place people and live and dead animals in close contact, making it easy for a virus to jump species.

”Poorly regulated, live animal markets mixed with illegal wildlife trade offer a unique opportunity for viruses to spill over from wildlife hosts into the animal population,” the Wildlife Conservation Society said in a statement calling for the closure of all live animal markets.

According to the US-based Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) the Wuhan coronavirus likely started from a “spillover” incident when the virus was passed from animal to human.

“These spillovers happen through close human-to-animal contact, especially in markets where live and dead animals are sold for food,” it said in a 2019-nCoV explainer on its website.

“Ebola likely spilt over to humans from bats and non-human primates, MERS spilt over to humans from camels, and SARS spilt over from palm civets (which are) small mammals considered a delicacy in China.”

SNAKE THEORY

A controversial new study claims there is evidence 2019-nCoV came from snakes sold at Wuhan market.

The Journal of Medical Virology paper, published on January 22 found the virus appears to be a mix, or “recombination” of two coronaviruses, one that is known to infect bats and the other of unknown origin.

Researchers analysed the genetic sequence of 2019-nCoV for patterns in the genetic code that may reveal the host that the virus infects, according to a Live Science report analysing the paper.

Potential candidates for the role of virus host included marmots, hedgehogs, bats, birds, humans and snakes. Based on this analysis, they concluded that 2019-nCoV may have come from snakes.

“Our findings suggest that snake is the most probable wildlife animal reservoir for the 2019â€nCoV based on its RSCU bias resembling snake compared to other animals,” the authors wrote in their summary.

“Taken together, our results suggest that homologous recombination within the spike glycoprotein may contribute to crossâ€species transmission from snake to humans.”

The paper identifies two types of snake — the Chinese cobra and the Chinese banded krait — commonly found in southeastern China, where Wuhan is located, as likely sources of the outbreak.

However, some researchers not involved in the study are not convinced by the snake theory.

“They have no evidence snakes can be infected by this new coronavirus and serve as a host for it,” University of São Paulo virologist Paulo Eduardo Brandão told Nature News.

Another virologist, the University of Glasgow’s David Robertson, said there was no proof coronaviruses could infect hosts other than mammals and birds.

“Nothing supports snakes being involved,” he said.

However, Chinese scientists have already warned that while the new coronavirus appears to be milder than its cousins SARS and MERS, it is mutating at a much greater rate, meaning it has the potential to spread more quickly.

SYMPTOMS

According to the latest figures on Friday, there are now 844 cases worldwide, 830 of them in China. Of the 25 deaths, 24 were in Wuhan and one in Beijing.

Patients with confirmed 2019-nCoV infection have reportedly had mild to severe respiratory illness with symptoms including fever, cough, shortness of breath and gastric problems.

The virus is believed to have an incubation period of between two and 14 days, based on what has been seen previously with MERS.

Source: Center for Disease Control